This article is about the British East India Company. For the chartered East India Companies of other countries, see East India Company (disambiguation).

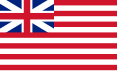

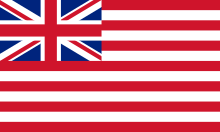

Company flag (1801) |

|

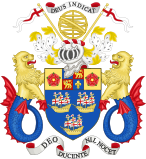

Coat of arms (1698) Motto: Auspicio Regis et Senatus Angliae |

|

| Type | Public State-owned enterprise[1] |

|---|---|

| Industry | International trade |

| Founded | 31 December 1600; 422 years ago |

| Founders |

|

| Defunct | 1 June 1874; 148 years ago |

| Fate | Nationalised:

|

| Headquarters | East India House,

London , Great Britain |

| Products | Cotton, silk, indigo dye, sugar, salt, spices, saltpetre, tea, slave trade and opium |

The East India Company (EIC)[a] was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600[b] and dissolved in 1874.[4] It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia), and later with East Asia. The company seized control of large parts of the Indian subcontinent, colonised parts of Southeast Asia and Hong Kong. At its peak, the company was the largest corporation in the world.[vague] The EIC had its own armed forces in the form of the company’s three Presidency armies, totalling about 260,000 soldiers, twice the size of the British army at the time.[5][6] The operations of the company had a profound effect on the global balance of trade, almost single-handedly[7] reversing the trend of eastward drain of Western bullion, seen since Roman times.[8]

Originally chartered as the «Governor and Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East-Indies»,[9][10] the company rose to account for half of the world’s trade during the mid-1700s and early 1800s,[11] particularly in basic commodities including cotton, silk, indigo dye, sugar, salt, spices, saltpetre, tea, and opium. The company also ruled the beginnings of the British Empire in India.[11][12]

The company eventually came to rule large areas of India, exercising military power and assuming administrative functions. Company rule in India effectively began in 1757 after the Battle of Plassey and lasted until 1858. Following the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the Government of India Act 1858 led to the British Crown assuming direct control of India in the form of the new British Raj.

Despite frequent government intervention, the company had recurring problems with its finances. The company was dissolved in 1874 as a result of the East India Stock Dividend Redemption Act enacted one year earlier, as the Government of India Act had by then rendered it vestigial, powerless, and obsolete. The official government machinery of the British Raj had assumed its governmental functions and absorbed its armies.

Origins[edit]

In 1577, Francis Drake set out on an expedition from England to plunder Spanish settlements in South America in search of gold and silver. Sailing in the Golden Hind he achieved this, and then sailed across the Pacific Ocean in 1579, known then only to the Spanish and Portuguese. Drake eventually sailed into the East Indies and came across the Moluccas, also known as the Spice Islands, and met Sultan Babullah. In exchange for linen, gold and silver, a large haul of exotic spices including cloves and nutmeg were obtained – the English initially not realising their huge value.[13] Drake returned to England in 1580 and became a hero; his circumnavigation raised an enormous amount of money for England’s coffers, and investors received a return of some 5,000 percent. Thus started an important element in the eastern design during the late sixteenth century.[14]

Soon after the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, the captured Spanish and Portuguese ships and cargoes enabled English voyagers to travel the globe in search of riches.[15] London merchants presented a petition to Queen Elizabeth I for permission to sail to the Indian Ocean.[16] The aim was to deliver a decisive blow to the Spanish and Portuguese monopoly of far-eastern trade.[17] Elizabeth granted her permission and on 10 April 1591, James Lancaster in the Bonaventure with two other ships, financed by the Levant Company[18] sailed from Torbay around the Cape of Good Hope to the Arabian Sea, becoming the first successful English expedition to India[18] via the Cape.[7]: 5 Having sailed around Cape Comorin to the Malay Peninsula, they preyed on Spanish and Portuguese ships there before returning to England in 1594.[16]

The biggest prize that galvanised English trade was the seizure of a large Portuguese carrack, the Madre de Deus, by Sir Walter Raleigh and the Earl of Cumberland at the Battle of Flores on 13 August 1592.[19] When she was brought in to Dartmouth she was the largest vessel ever seen in England and she carried chests of jewels, pearls, gold, silver coins, ambergris, cloth, tapestries, pepper, cloves, cinnamon, nutmeg, benjamin (a tree that produces frankincense), red dye, cochineal and ebony.[20] Equally valuable was the ship’s rutter (mariner’s handbook) containing vital information on the China, India, and Japan trade routes.[19]

In 1596, three more English ships sailed east but all were lost at sea.[16] A year later however saw the arrival of Ralph Fitch, an adventurer merchant who, with his companions, had made a remarkable fifteen-year overland journey to Mesopotamia, the Persian Gulf, the Indian Ocean, India and Southeast Asia.[21] Fitch was consulted on Indian affairs and gave even more valuable information to Lancaster.[22]

Formation[edit]

In 1599, a group of prominent merchants and explorers met to discuss a potential East Indies venture under a royal charter. Besides Fitch and Lancaster,[7]: 5 the group included Stephen Soame, then Lord Mayor of London; Thomas Smythe, a powerful London politician and administrator, whose father had established the Levant Company; Sir John Wolstenholme; Richard Hakluyt, writer and apologist for British colonization of the Americas; and several other sea-farers who had served with Drake and Raleigh.[7]: 1–2

On 22 September, the group stated their intention «to venture in the pretended voyage to the East Indies (the which it may please the Lord to prosper)» and to themselves invest £30,133 (over £4,000,000 in today’s money).[23][24] Two days later, the «Adventurers» reconvened and resolved to apply to the Queen for support of the project.[24] Although their first attempt had not been completely successful, they sought the Queen’s unofficial approval to continue. They bought ships for the venture and increased their investment to £68,373.

They convened again a year later, on 31 December 1600, and this time they succeeded; the Queen, responded favourably to a petition by «George, Earl of Cumberland and 218 others,[25] including James Lancaster, Sir John Harte, Sir John Spencer (both of whom had been Lord Mayor of London), the adventurer Edward Michelborne, the nobleman William Cavendish and other Aldermen and citizens.[26] She granted her charter to their corporation named Governor and Company of Merchants of London trading into the East Indies.[16] For a period of fifteen years, the charter awarded the company a monopoly[27] on English trade with all countries east of the Cape of Good Hope and west of the Straits of Magellan.[28] Any traders there without a licence from the company were liable to forfeiture of their ships and cargo (half of which would go to the Crown and half to the company), as well as imprisonment at the «royal pleasure».[29]

The charter named Thomas Smythe as the first governor[26]: 3 of the company, and 24 directors (including James Lancaster)[26]: 4 or «committees», who made up a Court of Directors. They, in turn, reported to a Court of Proprietors, who appointed them. Ten committees reported to the Court of Directors. By tradition, business was initially transacted at the Nags Head Inn, opposite St Botolph’s church in Bishopsgate, before moving to India House in Leadenhall Street.[30]

Early voyages to the East Indies[edit]

Sir James Lancaster commanded the first East India Company voyage in 1601 aboard Red Dragon.[31] The following year whilst sailing in the Malacca Straits Lancaster took the rich 1,200 ton Portuguese carrack Sao Thome carrying pepper and spices. The booty enabled the voyagers to set up two «factories» – one at Bantam on Java and another in the Moluccas (Spice Islands) before leaving.[32] They returned to England in 1603 to learn of Elizabeth’s death but Lancaster was knighted by the new king, James I on account of the voyage’s success.[33] By this time, the war with Spain had ended but the company had profitably breached the Spanish-Portuguese duopoly; new horizons opened for the English.[17]

In March 1604, Sir Henry Middleton commanded the second voyage. General William Keeling, a captain during the second voyage, led the third voyage aboard Red Dragon from 1607 to 1610 along with Hector under Captain William Hawkins and Consent under Captain David Middleton.[34]

Early in 1608 Alexander Sharpeigh was made captain of the company’s Ascension, and general or commander of the fourth voyage. Thereafter two ships, Ascension and Union (captained by Richard Rowles) sailed from Woolwich on 14 March 1608.[34] This expedition would be lost.[35]

| Year | Vessels | Total Invested £ | Bullion sent £ | Goods sent £ | Ships & Provisions £ | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1603 | 3 | 60,450 | 11,160 | 1,142 | 48,140 | |

| 1606 | 3 | 58,500 | 17,600 | 7,280 | 28,620 | |

| 1607 | 2 | 38,000 | 15,000 | 3,400 | 14,600 | Vessels lost |

| 1608 | 1 | 13,700 | 6,000 | 1,700 | 6,000 | |

| 1609 | 3 | 82,000 | 28,500 | 21,300 | 32,000 | |

| 1610 | 4 | 71,581 | 19,200 | 10,081 | 42,500 | |

| 1611 | 4 | 76,355 | 17,675 | 10,000 | 48,700 | |

| 1612 | 1 | 7,200 | 1,250 | 650 | 5,300 | |

| 1613 | 8 | 272,544 | 18,810 | 12,446 | ||

| 1614 | 8 | 13,942 | 23,000 | |||

| 1615 | 6 | 26,660 | 26,065 | |||

| 1616 | 7 | 52,087 | 16,506 |

Initially, the company struggled in the spice trade because of competition from the well-established Dutch East India Company. The English company opened a factory in Bantam on Java on its first voyage, and imports of pepper from Java remained an important part of the company’s trade for twenty years. The Bantam factory closed in 1683.

The emperor Jahangir investing a courtier with a robe of honour, watched by Sir Thomas Roe, English ambassador to the court of Jahangir at Agra from 1615 to 1618, and others

English traders frequently fought their Dutch and Portuguese counterparts in the Indian Ocean. The company achieved a major victory over the Portuguese in the Battle of Swally in 1612, at Suvali in Surat. The company decided to explore the feasibility of a foothold in mainland India, with official sanction from both Britain and the Mughal Empire, and requested that the Crown launch a diplomatic mission.[36]

Foothold in India[edit]

Company ships docked at Surat in Gujarat in 1608.[37] The company established its first Indian factory in 1615 at Surat,[37] and its second in 1616 at Masulipatnam on the Andhra Coast of the Bay of Bengal. The high profits reported by the company after landing in India initially prompted James I to grant subsidiary licences to other trading companies in England. However, in 1609 he renewed the East India Company’s charter for an indefinite period, with the proviso that its privileges would be annulled if trade was unprofitable for three consecutive years.

In 1615, James I instructed Sir Thomas Roe to visit the Mughal Emperor Nur-ud-din Salim Jahangir (r. 1605–1627) to arrange for a commercial treaty that would give the company exclusive rights to reside and establish factories in Surat and other areas. In return, the company offered to provide the Emperor with goods and rarities from the European market. This mission was highly successful, and Jahangir sent a letter to James through Sir Thomas Roe:[36]

Upon which assurance of your royal love I have given my general command to all the kingdoms and ports of my dominions to receive all the merchants of the English nation as the subjects of my friend; that in what place soever they choose to live, they may have free liberty without any restraint; and at what port soever they shall arrive, that neither Portugal nor any other shall dare to molest their quiet; and in what city soever they shall have residence, I have commanded all my governors and captains to give them freedom answerable to their own desires; to sell, buy, and to transport into their country at their pleasure.

For confirmation of our love and friendship, I desire your Majesty to command your merchants to bring in their ships of all sorts of rarities and rich goods fit for my palace; and that you be pleased to send me your royal letters by every opportunity, that I may rejoice in your health and prosperous affairs; that our friendship may be interchanged and eternal.— Nuruddin Salim Jahangir, Letter to James I.

Expansion[edit]

The company, which benefited from the imperial patronage, soon expanded its commercial trading operations. It eclipsed the Portuguese Estado da Índia, which had established bases in Goa, Chittagong, and Bombay – Portugal later ceded Bombay to England as part of the dowry of Catherine of Braganza on her marriage to King Charles II. The East India Company also launched a joint attack with the Dutch United East India Company (VOC) on Portuguese and Spanish ships off the coast of China that helped secure EIC ports in China,[38] independently attacking the Portuguese in the Persian Gulf Residencies primarily for political reasons.[39] The company established trading posts in Surat (1619) and Madras (1639).[40] By 1647, the company had 23 factories and settlements in India, and 90 employees.[41] The Crown turned Bombay over to the company in 1668, and the company established a presence in Calcutta in 1690.[40] The major factories became the walled forts of Fort William in Bengal, Fort St George in Madras, and Bombay Castle.

In 1634, the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan extended his hospitality to the English traders to the region of Bengal,[42] and in 1717 customs duties were completely waived for the English in Bengal. The company’s mainstay businesses were by then cotton, silk, indigo dye, saltpetre, and tea. The Dutch were aggressive competitors and had meanwhile expanded their monopoly of the spice trade in the Straits of Malacca by ousting the Portuguese in 1640–1641. With reduced Portuguese and Spanish influence in the region, the EIC and VOC entered a period of intense competition, resulting in the Anglo-Dutch Wars of the 17th and 18th centuries.

Within the first two decades of the 17th century, the Dutch East India Company or Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, (VOC) was the wealthiest commercial operation in the world with 50,000 employees worldwide and a private fleet of 200 ships. It specialised in the spice trade and gave its shareholders 40% annual dividend.[43]

The British East India Company was fiercely competitive with the Dutch and French throughout the 17th and 18th centuries over spices from the Spice Islands. Some spices, at the time, could only be found on these islands, such as nutmeg and cloves; and they could bring profits as high as 400 percent from one voyage.[44]

The tension was so high between the Dutch and the British East Indies Trading Companies that it escalated into at least four Anglo-Dutch Wars:[44] 1652–1654, 1665–1667, 1672–1674 and 1780–1784.

Competition arose in 1635 when Charles I granted a trading licence to Sir William Courteen, which permitted the rival Courteen association to trade with the east at any location in which the EIC had no presence.[45]

In an act aimed at strengthening the power of the EIC, King Charles II granted the EIC (in a series of five acts around 1670) the rights to autonomous territorial acquisitions, to mint money, to command fortresses and troops and form alliances, to make war and peace, and to exercise both civil and criminal jurisdiction over the acquired areas.[46]

In 1689 a Mughal fleet commanded by Sidi Yaqub attacked Bombay. After a year of resistance the EIC surrendered in 1690, and the company sent envoys to Aurangzeb’s camp to plead for a pardon. The company’s envoys had to prostrate themselves before the emperor, pay a large indemnity, and promise better behaviour in the future. The emperor withdrew his troops, and the company subsequently re-established itself in Bombay and set up a new base in Calcutta.[47]

| Years | EIC | VOC | France | EdI | Denmark | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bengal | Madras | Bombay | Surat | EIC (total) | VOC (total) | |||||

| 1665–1669 | 7,041 | 37,078 | 95,558 | 139,677 | 126,572 | 266,249 | ||||

| 1670–1674 | 46,510 | 169,052 | 294,959 | 510,521 | 257,918 | 768,439 | ||||

| 1675–1679 | 66,764 | 193,303 | 309,480 | 569,547 | 127,459 | 697,006 | ||||

| 1680–1684 | 107,669 | 408,032 | 452,083 | 967,784 | 283,456 | 1,251,240 | ||||

| 1685–1689 | 169,595 | 244,065 | 200,766 | 614,426 | 316,167 | 930,593 | ||||

| 1690–1694 | 59,390 | 23,011 | 89,486 | 171,887 | 156,891 | 328,778 | ||||

| 1695–1699 | 130,910 | 107,909 | 148,704 | 387,523 | 364,613 | 752,136 | ||||

| 1700–1704 | 197,012 | 104,939 | 296,027 | 597,978 | 310,611 | 908,589 | ||||

| 1705–1709 | 70,594 | 99,038 | 34,382 | 204,014 | 294,886 | 498,900 | ||||

| 1710–1714 | 260,318 | 150,042 | 164,742 | 575,102 | 372,601 | 947,703 | ||||

| 1715–1719 | 251,585 | 20,049 | 582,108 | 534,188 | 435,923 | 970,111 | ||||

| 1720–1724 | 341,925 | 269,653 | 184,715 | 796,293 | 475,752 | 1,272,045 | ||||

| 1725–1729 | 558,850 | 142,500 | 119,962 | 821,312 | 399,477 | 1,220,789 | ||||

| 1730–1734 | 583,707 | 86,606 | 57,503 | 727,816 | 241,070 | 968,886 | ||||

| 1735–1739 | 580,458 | 137,233 | 66,981 | 784,672 | 315,543 | 1,100,215 | ||||

| 1740–1744 | 619,309 | 98,252 | 295,139 | 812,700 | 288,050 | 1,100,750 | ||||

| 1745–1749 | 479,593 | 144,553 | 60,042 | 684,188 | 262,261 | 946,449 | ||||

| 1750–1754 | 406,706 | 169,892 | 55,576 | 632,174 | 532,865 | 1,165,039 | ||||

| 1755–1759 | 307,776 | 106,646 | 55,770 | 470,192 | 321,251 | 791,443 |

Slavery 1621–1834[edit]

The East India Company’s archives suggest its involvement in the slave trade began in 1684, when a Captain Robert Knox was ordered to buy and transport 250 slaves from Madagascar to St. Helena.[49] The East India Company began using and transporting slaves in Asia and the Atlantic in the early 1620s, according to the Encyclopædia Britannica,[50] or in 1621, according to Richard Allen.[51] Eventually, the company ended the trade in 1834 after numerous legal threats from the British state and the Royal Navy in the form of the West Africa Squadron, which discovered various ships had contained evidence of the illegal trade.[52]

Japan[edit]

Document with the original vermilion seal of Tokugawa Ieyasu, granting trade privileges in Japan to the East India Company in 1613

In 1613, during the rule of Tokugawa Hidetada of the Tokugawa shogunate, the British ship Clove, under the command of Captain John Saris, was the first British ship to call on Japan. Saris was the chief factor of the EIC’s trading post in Java, and with the assistance of William Adams, a British sailor who had arrived in Japan in 1600, he was able to gain permission from the ruler to establish a commercial house in Hirado on the Japanese island of Kyushu:

We give free license to the subjects of the King of Great Britaine, Sir Thomas Smythe, Governor and Company of the East Indian Merchants and Adventurers forever safely come into any of our ports of our Empire of Japan with their shippes and merchandise, without any hindrance to them or their goods, and to abide, buy, sell and barter according to their own manner with all nations, to tarry here as long as they think good, and to depart at their pleasure.[53]

However, unable to obtain Japanese raw silk for export to China and with their trading area reduced to Hirado and Nagasaki from 1616 onwards, the company closed its factory in 1623.[54]

Anglo-Mughal War[edit]

The first of the Anglo-Indian Wars occurred in 1686 when the company conducted naval operations against Shaista Khan, the governor of Mughal Bengal. This led to the siege of Bombay and the subsequent intervention of the Mughal Emperor, Aurangzeb. Subsequently, the English company was defeated and fined.[55][56]

Mughal convoy piracy incident of 1695[edit]

In September 1695, Captain Henry Every, an English pirate on board the Fancy, reached the Straits of Bab-el-Mandeb, where he teamed up with five other pirate captains to make an attack on the Indian fleet on return from the annual pilgrimage to Mecca. The Mughal convoy included the treasure-laden Ganj-i-Sawai, reported to be the greatest in the Mughal fleet and the largest ship operational in the Indian Ocean, and its escort, the Fateh Muhammed. They were spotted passing the straits en route to Surat. The pirates gave chase and caught up with Fateh Muhammed some days later, and meeting little resistance, took some £50,000 to £60,000 worth of treasure.[57]

Every continued in pursuit and managed to overhaul Ganj-i-Sawai, which resisted strongly before eventually striking. Ganj-i-Sawai carried enormous wealth and, according to contemporary East India Company sources, was carrying a relative of the Grand Mughal, though there is no evidence to suggest that it was his daughter and her retinue. The loot from the Ganj-i-Sawai had a total value between £325,000 and £600,000, including 500,000 gold and silver pieces, and has become known as the richest ship ever taken by pirates.[58]

When the news arrived in England it caused an outcry. To appease Aurangzeb, the East India Company promised to pay all financial reparations, while Parliament declared the pirates hostis humani generis («the enemy of humanity»). In mid-1696 the government issued a £500 bounty on Every’s head and offered a free pardon to any informer who disclosed his whereabouts. When the East India Company later doubled that reward, the first worldwide manhunt in recorded history was underway.[59]

The plunder of Aurangzeb’s treasure ship had serious consequences for the English East India Company. The furious Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb ordered Sidi Yaqub and Nawab Daud Khan to attack and close four of the company’s factories in India and imprison their officers, who were almost lynched by a mob of angry Mughals, blaming them for their countryman’s depredations, and threatened to put an end to all English trading in India. To appease Emperor Aurangzeb and particularly his Grand Vizier Asad Khan, Parliament exempted Every from all of the Acts of Grace (pardons) and amnesties it would subsequently issue to other pirates.[60][disputed – discuss]

-

English, Dutch and Danish factories at Mocha

-

An 18th-century depiction of Henry Every, with the Fancy shown engaging its prey in the background

-

Depiction of Captain Every’s encounter with the Mughal Emperor’s granddaughter after his September 1695 capture of the Mughal trader Ganj-i-Sawai

Forming a complete monopoly[edit]

Trade monopoly[edit]

Rear view of the East India Company’s factory at Cossimbazar

The prosperity that the officers of the company enjoyed allowed them to return to Britain and establish sprawling estates and businesses, and to obtain political power. The company developed a lobby in the English parliament. Under pressure from ambitious tradesmen and former associates of the company (pejoratively termed Interlopers by the company), who wanted to establish private trading firms in India, a deregulating act was passed in 1694.[61]

This allowed any English firm to trade with India, unless specifically prohibited by act of parliament, thereby annulling the charter that had been in force for almost 100 years. When the East India Company Act 1697 (9 Will. c. 44) was passed in 1697, a new «parallel» East India Company (officially titled the English Company Trading to the East Indies) was floated under a state-backed indemnity of £2 million.[62] The powerful stockholders of the old company quickly subscribed a sum of £315,000 in the new concern, and dominated the new body. The two companies wrestled with each other for some time, both in England and in India, for a dominant share of the trade.[61]

It quickly became evident that, in practice, the original company faced scarcely any measurable competition. The companies merged in 1708, by a tripartite indenture involving both companies and the state, with the charter and agreement for the new United Company of Merchants of England Trading to the East Indies being awarded by Sidney Godolphin, 1st Earl of Godolphin.[63] Under this arrangement, the merged company lent to the Treasury a sum of £3,200,000, in return for exclusive privileges for the next three years, after which the situation was to be reviewed. The amalgamated company became the United Company of Merchants of England Trading to the East Indies.[61]

In the following decades there was a constant battle between the company lobby and Parliament. The company sought a permanent establishment, while Parliament would not willingly allow it greater autonomy and so relinquish the opportunity to exploit the company’s profits. In 1712, another act renewed the status of the company, though the debts were repaid. By 1720, 15% of British imports were from India, almost all passing through the company, which reasserted the influence of the company lobby. The licence was prolonged until 1766 by yet another act in 1730.[citation needed]

At this time, Britain and France became bitter rivals. Frequent skirmishes between them took place for control of colonial possessions. In 1742, fearing the monetary consequences of a war, the British government agreed to extend the deadline for the licensed exclusive trade by the company in India until 1783, in return for a further loan of £1 million. Between 1756 and 1763, the Seven Years’ War diverted the state’s attention towards consolidation and defence of its territorial possessions in Europe and its colonies in North America.[64]

The war partly took place in the Indian theater, between the company troops and the French forces. In 1757, the Law Officers of the Crown delivered the Pratt–Yorke opinion distinguishing overseas territories acquired by right of conquest from those acquired by private treaty. The opinion asserted that, while the Crown of Great Britain enjoyed sovereignty over both, only the property of the former was vested in the Crown.[64]

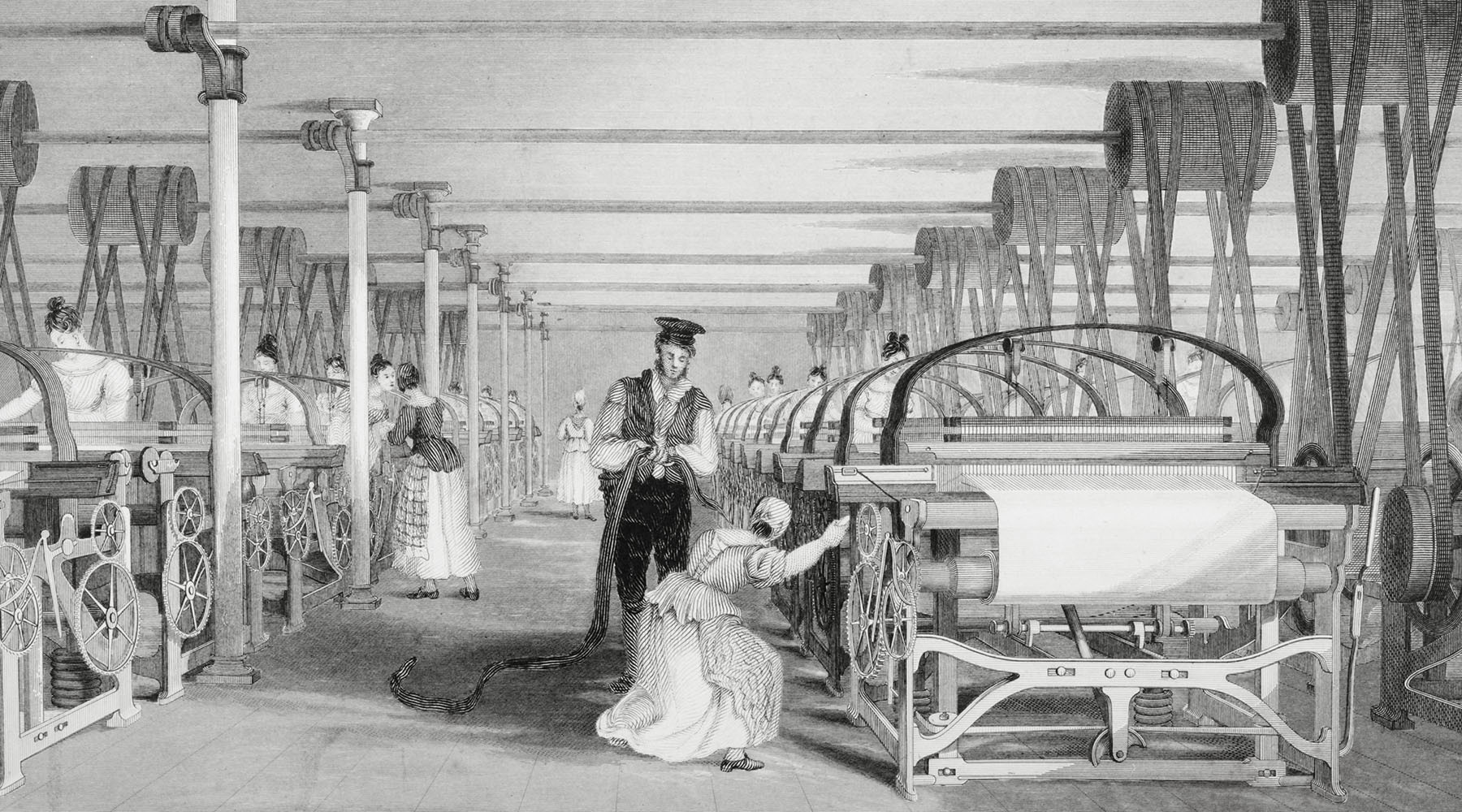

With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, Britain surged ahead of its European rivals. Demand for Indian commodities was boosted by the need to sustain the troops and the economy during the war, and by the increased availability of raw materials and efficient methods of production. As home to the revolution, Britain experienced higher standards of living. Its spiralling cycle of prosperity, demand and production had a profound influence on overseas trade. The company became the single largest player in the British global market. In 1801 Henry Dundas reported to the House of Commons that

… on the 1st March, 1801, the debts of the East India Company amounted to 5,393,989l. their effects to 15,404,736l. and that their sales had increased since February 1793, from 4,988,300l. to 7,602,041l.[65]

Saltpetre trade[edit]

Sir John Banks, a businessman from Kent who negotiated an agreement between the king and the company, began his career in a syndicate arranging contracts for victualling the navy, an interest he kept up for most of his life. He knew that Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn had amassed a substantial fortune from the Levant and Indian trades.

He became a director and later, as governor of the East India Company in 1672, he arranged a contract which included a loan of £20,000 and £30,000 worth of saltpetre—also known as potassium nitrate, a primary ingredient in gunpowder—for the King «at the price it shall sell by the candle»—that is by auction—where bidding could continue as long as an inch-long candle remained alight.[66]

Outstanding debts were also agreed and the company permitted to export 250 tons of saltpetre. Again in 1673, Banks successfully negotiated another contract for 700 tons of saltpetre at £37,000 between the king and the company. So high was the demand from armed forces that the authorities sometimes turned a blind eye on the untaxed sales. One governor of the company was even reported as saying in 1864 that he would rather have the saltpetre made than the tax on salt.[67]

Basis for the monopoly[edit]

Colonial monopoly[edit]

The Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) resulted in the defeat of the French forces, limited French imperial ambitions, and stunted the influence of the Industrial Revolution in French territories. Robert Clive, the Governor-General, led the company to a victory against Joseph François Dupleix, the commander of the French forces in India, and recaptured Fort St George from the French. The company took this respite to seize Manila in 1762.[68][better source needed]

By the Treaty of Paris, France regained the five establishments captured by the British during the war (Pondichéry, Mahe, Karaikal, Yanam and Chandernagar) but was prevented from erecting fortifications and keeping troops in Bengal (art. XI). Elsewhere in India, the French were to remain a military threat, particularly during the War of American Independence, and up to the capture of Pondichéry in 1793 at the outset of the French Revolutionary Wars without any military presence. Although these small outposts remained French possessions for the next two hundred years, French ambitions on Indian territories were effectively laid to rest, thus eliminating a major source of economic competition for the company.

The Great Bengal famine of 1770, which was exacerbated by the actions of the East India Company, led to massive shortfalls in expected land values for the company. The Company bore heavy losses and its stock price fell significantly. In May 1772 the EIC stock price rose significantly. In June Alexander Fordyce lost £300,000 shorting EIC stock, leaving his partners liable for an estimated £243,000 in debts.[69] As this information became public, 20–30 banks across Europe collapsed during the British credit crisis of 1772-1773.[70][71] In India alone, the company had bill debts of £1.2 million. It seems that EIC directors James Cockburn and George Colebrooke were «bulling» the Amsterdam market during 1772.[72] The root of this crisis in relation to the East India Company came from the prediction by Isaac de Pinto that ‘peace conditions plus an abundance of money would push East Indian shares to ‘exorbitant heights.’[73]

In September the company took out a loan from the Bank of England, to be repaid from the sale of goods later that month. But with buyers scarce,

most of the sale had to be postponed, and when the loan fell due, the company’s coffers were empty. On October 29 the bank refused to renew the loan. That decision set in motion a chain of events that made the American Revolution inevitable. The East India Company had eighteen million pounds of tea sitting in British warehouses. A huge amount of tea as assets which were lying unsold. Selling it in a hurry would do wonders for its finances.[74]

On 14 January 1773 the directors of the EIC asked for a government loan and unlimited access to the tea market in the American colonies, both of which were granted.[75] In August 1773 the Bank of England assisted the EIC with a loan.[76]

The East India Company had also been granted competitive advantages over colonial American tea importers to sell tea from its colonies in Asia in American colonies. This led to the Boston Tea Party of 1773 in which protesters boarded British ships and threw the tea overboard. When protesters successfully prevented the unloading of tea in three other colonies and in Boston, Governor Thomas Hutchinson of the Province of Massachusetts Bay refused to allow the tea to be returned to Britain. This was one of the incidents which led to the American Revolution and independence of the American colonies.[77]

The company’s trade monopoly with India was abolished in the Charter Act of 1813. The monopoly with China was ended in 1833, ending the trading activities of the company and rendering its activities purely administrative.

Disestablishment[edit]

In the aftermath of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 and under the provisions of the Government of India Act 1858, the British Government nationalised the company. The British government took over its Indian possessions, its administrative powers and machinery, and its armed forces.

The company had already divested itself of its commercial trading assets in India in favour of the UK government in 1833, with the latter assuming the debts and obligations of the company, which were to be serviced and paid from tax revenue raised in India. In return, the shareholders voted to accept an annual dividend of 10.5%, guaranteed for forty years, likewise to be funded from India, with a final pay-off to redeem outstanding shares. The debt obligations continued beyond dissolution, and were only extinguished by the UK government during the Second World War.[78]

The company remained in existence in vestigial form, continuing to manage the tea trade on behalf of the British Government (and the supply of Saint Helena) until the East India Stock Dividend Redemption Act 1873 came into effect, on 1 January 1874. This Act provided for the formal dissolution of the company on 1 June 1874, after a final dividend payment and the commutation or redemption of its stock.[79] The Times commented on 8 April 1873:[4]

«It accomplished a work such as in the whole history of the human race no other trading Company ever attempted, and such as none, surely, is likely to attempt in the years to come.»

Establishments in Britain[edit]

The company’s headquarters in London, from which much of India was governed, was East India House in Leadenhall Street. After occupying premises in Philpot Lane from 1600 to 1621; in Crosby House, Bishopsgate from 1621 to 1638; and in Leadenhall Street from 1638 to 1648, the company moved into Craven House, an Elizabethan mansion in Leadenhall Street. The building had become known as East India House by 1661. It was completely rebuilt and enlarged in 1726–1729 and further significantly remodelled and expanded in 1796–1800. It was finally vacated in 1860 and demolished in 1861–1862.[80] The site is now occupied by the Lloyd’s building.

In 1607, the company decided to build its own ships and leased a yard on the River Thames at Deptford. By 1614, the yard having become too small, an alternative site was acquired at Blackwall: the new yard was fully operational by 1617. It was sold in 1656, although for some years East India Company ships continued to be built and repaired there under the new owners.[81]

In 1803 an Act of Parliament, promoted by the East India Company, established the East India Dock Company, with the aim of establishing a new set of docks (the East India Docks) primarily for the use of ships trading with India. The existing Brunswick Dock, part of the Blackwall Yard site, became the Export Dock; while a new Import Dock was built to the north. In 1838 the East India Dock Company merged with the West India Dock Company. The docks were taken over by the Port of London Authority in 1909, and closed in 1967.[82]

The East India College was founded in 1806 as a training establishment for «writers» (i.e. clerks) in the company’s service. It was initially located in Hertford Castle, but moved in 1809 to purpose-built premises at Hertford Heath, Hertfordshire. In 1858 the college closed; but in 1862 the buildings reopened as a public school, now Haileybury and Imperial Service College.[83][84]

The East India Company Military Seminary was founded in 1809 at Addiscombe, near Croydon, Surrey, to train young officers for service in the company’s armies in India. It was based in Addiscombe Place, an early 18th-century mansion. The government took it over in 1858, and renamed it the Royal Indian Military College. In 1861 it was closed, and the site was subsequently redeveloped.[85][86]

In 1818, the company entered into an agreement by which those of its servants who were certified insane in India might be cared for at Pembroke House, Hackney, London, a private lunatic asylum run by Dr George Rees until 1838, and thereafter by Dr William Williams. The arrangement outlasted the company itself, continuing until 1870, when the India Office opened its own asylum, the Royal India Asylum, at Hanwell, Middlesex.[87][88]

The East India Club in London was formed in 1849 for officers of the company. The Club still exists today as a private gentlemen’s club with its club house situated at 16 St James’s Square, London.[89][90]

Symbols[edit]

Flags[edit]

- Historical depictions

-

Downman (1685)

-

Lens (1700)

-

-

Rees (1820)

-

Laurie (1842)

- Modern depictions

-

1600–1707

-

1707–1801

-

1801–1874

The English East India Company flag changed over time, with a canton based on the flag of the contemporary Kingdom, and a field of 9-to-13 alternating red and white stripes.

From 1600, the canton consisted of a St George’s Cross representing the Kingdom of England. With the Acts of Union 1707, the canton was changed to the new Union Flag—consisting of an English St George’s Cross combined with a Scottish St Andrew’s cross—representing the Kingdom of Great Britain. After the Acts of Union 1800 that joined Ireland with Great Britain to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, the canton of the East India Company flag was altered accordingly to include a Saint Patrick’s Saltire.

There has been much debate about the number and order of stripes in the field of the flag. Historical documents and paintings show variations from 9-to-13 stripes, with some images showing the top stripe red and others showing it white.

At the time of the American Revolution the East India Company flag was nearly identical to the Grand Union Flag. Historian Charles Fawcett argued that the East India Company Flag inspired the Stars and Stripes of America.[91]

Coat of arms[edit]

The original coat of arms of the East India Company (1600)

The later coat of arms of the East India Company (1698)

The East India Company’s original coat of arms was granted in 1600. The blazon of the arms is as follows:

«Azure, three ships with three masts, rigged and under full sail, the sails, pennants and ensigns Argent, each charged with a cross Gules; on a chief of the second a pale quarterly Azure and Gules, on the 1st and 4th a fleur-de-lis or, on the 2nd and 3rd a leopard or, between two roses Gules seeded Or barbed Vert.» The shield had as a crest: «A sphere without a frame, bounded with the Zodiac in bend Or, between two pennants flottant Argent, each charged with a cross Gules, over the sphere the words Deus indicat» (Latin: God Indicates). The supporters were two sea lions (lions with fishes’ tails) and the motto was Deo ducente nil nocet (Latin: Where God Leads, Nothing Harms).[92]

The East India Company’s later arms, granted in 1698, were: «Argent a cross Gules; in the dexter chief quarter an escutcheon of the arms of France and England quarterly, the shield ornamentally and regally crowned Or.» The crest was: «A lion rampant guardant Or holding between the forepaws a regal crown proper.» The supporters were: «Two lions rampant guardant Or, each supporting a banner erect Argent, charged with a cross Gules.» The motto was Auspicio regis et senatus angliæ (Latin: Under the auspices of the King and the Parliament of England).[92]

Merchant mark[edit]

When the East India Company was chartered in 1600, it was still customary for individual merchants or members of companies such as the Company of Merchant Adventurers to have a distinguishing merchant’s mark which often included the mystical «Sign of Four» and served as a trademark. The East India Company’s merchant mark consisted of a «Sign of Four» atop a heart within which was a saltire between the lower arms of which were the initials «EIC». This mark was a central motif of the East India Company’s coinage[93] and forms the central emblem displayed on the Scinde Dawk postage stamps.[94]

Ships[edit]

Ships of the East India Company were called East Indiamen or simply «Indiamen».[95] Their names were sometimes prefixed with the initials «HCS», standing for «Honourable Company’s Service»[96] or «Honourable Company’s Ship»,[97] such as HCS Vestal (1809) and HCS Intrepid (1780).

Royal George was one of the five East Indiamen the Spanish fleet captured in 1780

During the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, the East India Company arranged for letters of marque for its vessels such as Lord Nelson. This was not so that they could carry cannon to fend off warships, privateers, and pirates on their voyages to India and China (that they could do without permission) but so that, should they have the opportunity to take a prize, they could do so without being guilty of piracy. Similarly, the Earl of Mornington, an East India Company packet ship of only six guns, also sailed under a letter of marque.

In addition, the company had its own navy, the Bombay Marine, equipped with warships such as Grappler. These vessels often accompanied vessels of the Royal Navy on expeditions, such as the Invasion of Java.

At the Battle of Pulo Aura, which was probably the company’s most notable naval victory, Nathaniel Dance, Commodore of a convoy of Indiamen and sailing aboard the Warley, led several Indiamen in a skirmish with a French squadron, driving them off. Some six years earlier, on 28 January 1797, five Indiamen, Woodford, under Captain Charles Lennox, Taunton-Castle, Captain Edward Studd, Canton, Captain Abel Vyvyan, Boddam, Captain George Palmer, and Ocean, Captain John Christian Lochner, had encountered Admiral de Sercey and his squadron of frigates. On this occasion the Indiamen succeeded in bluffing their way to safety, and without any shots even being fired. Lastly, on 15 June 1795, General Goddard played a large role in the capture of seven Dutch East Indiamen off St Helena.

East Indiamen were large and strongly built and when the Royal Navy was desperate for vessels to escort merchant convoys it bought several of them to convert to warships. Earl of Mornington became HMS Drake. Other examples include:

- HMS Calcutta

- HMS Glatton

- HMS Hindostan (1795)

- HMS Hindostan (1804)

- HMS Malabar

- HMS Buffalo

Their design as merchant vessels meant that their performance in the warship role was underwhelming and the Navy converted them to transports.

Records[edit]

Unlike all other British Government records, the records from the East India Company (and its successor the India Office) are not in The National Archives at Kew, London, but are held by the British Library in London as part of the Asia, Pacific and Africa Collections. The catalogue is searchable online in the Access to Archives catalogues.[98] Many of the East India Company records are freely available online under an agreement that the Families in British India Society has with the British Library. Published catalogues exist of East India Company ships’ journals and logs, 1600–1834;[99] and of some of the company’s daughter institutions, including the East India Company College, Haileybury, and Addiscombe Military Seminary.[84]

The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British India and its Dependencies, first issued in 1816, was sponsored by the East India Company, and includes much information relating to the EIC.

Early governors[edit]

- 1600–1601: Sir Thomas Smythe (first governor)

- 1601–1602: Sir John Watts

- 1602–1603: Sir John Harts

- 1606–1607: Sir William Romney

- 1607–1621: Sir Thomas Smythe

- 1621–1624: Sir William Halliday

- 1624–1638: Sir Maurice (Morris) Abbot

- 1638–1641: Sir Christopher Clitherow[100]

See also[edit]

East India Company[edit]

- Company rule in India

- Economy of India under Company rule

- Governor-General of India

- Chief Justice of Bengal

- Advocate-General of Bengal

- Chief Justice of Madras

- Presidency armies

- Indian Rebellion of 1857

- Indian independence movement

- List of East India Company directors

- List of trading companies

- East India Company Cemetery in Macau

- Category:Honourable East India Company regiments

General[edit]

- British Imperial Lifeline

- Lascar

- Carnatic Wars

- Commercial Revolution

- Political warfare in British colonial India

- Trade between Western Europe and the Mughal Empire in the 17th century

- Whampoa anchorage

Notes[edit]

- ^ also known as the Honourable East India Company (HEIC), East India Trading Company (EITC), the English East India Company, or (after 1707) the British East India Company, and informally known as John Company,[2] Company Bahadur,[3] or simply The Company

- ^ The Dutch East India Company was the first to issue public stock.

References[edit]

- ^ «East India Company | Definition, History, & Facts | Britannica». www.britannica.com.

- ^ Carey, W. H. (1882). 1882 – The Good Old Days of Honourable John Company. Simla: Argus Press. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ «Company Bahadur». Encyclopaedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 9 December 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ a b «Not many days ago the House of Commons passed». Times. London. 8 April 1873. p. 9.

- ^ Erikson, Emily (21 July 2014). Between Monopoly and Free Trade: The English East India Company, 1600–1757. Princeton.edu. ISBN 9780691159065. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ Roos, Dave (23 October 2020). «How the East India Company Became the World’s Most Powerful Monopoly». History. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d Dalrymple, William (2020). The Anarchy — The Relentless Rise of the East India Company. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. xxxv (Introduction). ISBN 9781526634016. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ Dalrymple, William (30 August 2019). «Lessons for capitalism from the East India Company». Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ Scott, William. «East India Company, 1817–1827». archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk. Senate House Library Archives, University of London. Archived from the original on 21 September 2019. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ Parliament of England (31 December 1600). Charter Granted by Queen Elizabeth to the East India Company – via Wikisource.

Governor and Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East-Indies

- ^ a b Farrington, Anthony (2002). Trading Places: The East India Company and Asia 1600–1834. British Library. ISBN 9780712347563. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- ^ «Books associated with Trading Places – the East India Company and Asia 1600–1834, an Exhibition». Archived from the original on 30 March 2014.

- ^ Wheeler, Jack (21 August 2017). «Sir Francis Drake and the Sultan». International Strategies For the Globally Minded. Escape Artist. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ Lawson 1993, p. 2

- ^ Desai, Tripta (1984). The East India Company: A Brief Survey from 1599 to 1857. Kanak Publications. p. 3. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d «Early European Settlements». Imperial Gazetteer of India. Vol. II. 1908. p. 454. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ^ a b Wernham, R.B (1994). The Return of the Armadas: The Last Years of the Elizabethan Wars Against Spain 1595–1603. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 333–334. ISBN 978-0-19-820443-5.

- ^ a b Holmes, Sir George Charles Vincent (1900). Ancient and Modern Ships Part I. London: Chapman & Hall. p. 93. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ a b McCulloch, John Ramsay (1833). A Treatise on the Principles, Practice, & History of Commerce. Baldwin and Cradock. p. 120.

- ^ Leinwand 2006, pp. 125–127.

- ^ ‘Ralph Fitch: An Elizabethan Merchant in Chiang Mai; and ‘Ralph Fitch’s Account of Chiang Mai in 1586–1587’ in: Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai Volume 1. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012.

- ^ Prasad, Ram Chandra (1980). Early English Travellers in India: A Study in the Travel Literature of the Elizabethan and Jacobean Periods with Particular Reference to India. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 45. ISBN 9788120824652. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Wilbur, Marguerite Eyer (1945). The East India Company: And the British Empire in the Far East. Stanford, Cal.: Stanford University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-8047-28645. Archived from the original on 30 May 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ^ a b «East Indies: September 1599». british-history.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 19 November 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- ^ United Service Magazine — and Naval and Military Journal (1875 — Part III). London: Hursett and Blackett. 1875. p. 148 (History of the Indian Navy). Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ a b c Shaw, John (1887). Charters Relating to the East India Company — From 1600 to 1761. Chennai: R. Hill, Government of Madras (British India). p. 1. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ The Imperial Gazetteer of India. Vol. II: The Indian Empire, Historical. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1908. p. 455.

- ^ «East India Company – Encyclopedia». theodora.com. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ Kerr, Robert (1813). A General History and Collection of Voyages and Travels. Vol. 8. W. Blackwood. p. 102. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Timbs, John (1855). Curiosities of London: Exhibiting the Most Rare and Remarkable Objects of Interest in the Metropolis. D. Bogue. p. 264.

- ^ Gardner, Brian (1990) [1971]. The East India Company: A History. Dorset Press. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-0-88029-530-7.

- ^ Dulles (1969), p106.

- ^ Foster, Sir William (1998). England’s quest of eastern trade (1933 ed.). London: A. & C. Black. p. 157. ISBN 9780415155182. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ a b East India Company (1897). List of Factory Records of the late East India Company: preserved in the Record Department of the India Office, London. p. vi.

- ^ a b James Mill (1817). «1». The History of British India. Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy. pp. 15–18. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ^ a b The battle of Plassey ended the tax on the Indian goods. «Indian History Sourcebook: England, India, and The East Indies, 1617 CE». Fordham University. Archived from the original on 18 August 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2004.

- ^ a b Tracy, James D. (2015). «Dutch and English Trade to the East». In Bentley, Jerry; Subrahmanyam, Sanjay; Wiesner-Hanks, Merry (eds.). The Construction of a Global World, 1400–1800 CE, Part 2, Patterns of Change. The Cambridge World History. Vol. 6. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 249. ISBN 9780521192460.

In 1608 an EIC ship called at Surat, the main port of Gujarat, and a good place to obtain the Gujarati cottons that had an established market in the Moluccas. But the English were not allowed to establish a factory here until 1615…

- ^ Tyacke, Sarah (2008). «Gabriel Tatton’s Maritime Atlas of the East Indies, 1620–1621: Portsmouth Royal Naval Museum, Admiralty Library Manuscript, MSS 352». Imago Mundi. 60 (1): 39–62. doi:10.1080/03085690701669293. S2CID 162239597.

- ^ Chaudhuri, K. N. (1999). The English East India Company: The Study of an Early Joint-stock Company 1600-1640. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415190763.

- ^ a b Cadell, Patrick (1956). «The Raising of the Indian Army». Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 34 (139): 96, 98. JSTOR 44226533.

- ^ Woodruff, Philip (1954). The Men Who Ruled India: The Founders. Vol. 1. St. Martin’s Press. p. 55.

- ^ Dalrymple, William (24 August 2019). «East India Company sent a diplomat to Jahangir & all the Mughal Emperor cared about was beer». Archived from the original on 24 August 2019. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- ^ «The Nutmeg Wars». Neatorama. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ a b Suijk, Paul (Director) (2015). 1600 The British East India Company [The Great Courses (Episode 5, 13:16] (on-line video). Brentwood Associates/The Teaching Company Sales. Chantilly, VA, USA: Liulevicius, Professor Vejas Gabriel (lecturer).

- ^ Riddick, John F. (2006). The history of British India: a chronology. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-313-32280-8. Archived from the original on 4 October 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- ^ «East India Company» (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, Volume 8, p.835

- ^ «Asia facts, information, pictures – Encyclopedia.com articles about Asia». encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ^ Broadberry, Stephen; Gupta, Bishnupriya. «The Rise, Organization, and Institutional Framework of Factor Markets». International Institute of Social history. Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ^ Pinkston, Bonnie (3 October 2018). «Documenting the British East India Company and their Involvement in the East Indian Slave Trade». SLIS Connecting. 7 (1): 53–59. doi:10.18785/slis.0701.10. ISSN 2330-2917. Archived from the original on 22 June 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ «East India Company | Definition, History, & Facts». Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ Allen, Richard B. (2015). European Slave Trading in the Indian Ocean, 1500–1850. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press. ISBN 9780821421062. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ «1834: the end of slavery?». Historic England. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ Wilbur, Marguerite Eyer (1945). The East India Company: And the British Empire in the Far East. Stanford University Press. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-0-8047-2864-5. Archived from the original on 30 May 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ^ Hayami, Akira (2015). Japan’s Industrious Revolution: Economic and Social Transformations in the Early Modern Period. Springer. p. 49. ISBN 978-4-431-55142-3. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ^ Hasan, Farhat (1991). «Conflict and Cooperation in Anglo-Mughal Trade Relations during the Reign of Aurangzeb». Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 34 (4): 351–360. doi:10.1163/156852091X00058. JSTOR 3632456.

- ^ Vaugn, James (September 2017). «John Company Armed: The English East India Company, the Anglo-Mughal War and Absolutist Imperialism, c. 1675–1690». Britain and the World. 11 (1).

- ^ Burgess, Douglas R (2009). The Pirates’ Pact: The Secret Alliances Between History’s Most Notorious Buccaneers and Colonial America. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-147476-4.

- ^ Sims-Williams, Ursula. «The highjacking of the Ganj-i Sawaʼi». The British Library. Archived from the original on 16 June 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ Burgess 2009, p. 144

- ^ Fox, E. T. (2008). King of the Pirates: The Swashbuckling Life of Henry Every. London: Tempus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7524-4718-6.

- ^ a b c «The British East India Company – the Company that Owned a Nation (or Two)». victorianweb.org. Archived from the original on 19 March 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2010.

- ^ Boggart, Dan (2017). Lamoreaux, Naomi R.; Wallis, John Joseph (eds.). «East Indian Monopoly and Limited Access in England». Organizations, Civil Society, and the Roots of Development. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Company, East India; Shaw, John (1887). Charters Relating to the East India Company from 1600 to 1761: Reprinted from a Former Collection with Some Additions and a Preface for the Government of Madras. R. Hill at the Government Press. p. 217. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ a b Thomas, P. D. G. (2008) «Pratt, Charles, first Earl Camden (1714–1794) Archived 23 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine», Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, online edn. Retrieved 15 February 2008 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ Pyne, William Henry (1904) [1808]. The Microcosm of London, or London in Miniature. Vol. 2. London: Methuen. p. 159.

- ^ Janssens, Koen (2009). Annales Du 17e Congrès D’Associationi Internationale Pour L’histoire Du Verre. Asp / Vubpress / Upa. p. 366. ISBN 978-90-5487-618-2. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ^ «SALTPETER the secret salt – Salt made the world go round». salt.org.il. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ^ «The Seven Years’ War in the Philippines». Land Forces of Britain, the Empire and Commonwealth. Archived from the original on 10 July 2004. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ Tyler Goodspeed: Legislating Instability: Adam Smith, Free Banking, and the Financial Crisis of 1772

- ^ «The East India Company: The original corporate raiders | William Dalrymple». The Guardian. 4 March 2015. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ «The Credit Crisis of 1772 – Recession Tips». 26 November 2021.

- ^ Sutherland, L. (1952) The East India Company in eighteenth-century politics, Oxford UP , p. 228; SAA 735, 1155

- ^ The International Lender of Last Resort- An Historical Perspective by Joanna Rudd

- ^ «1772 Two Hundred And Twenty-five Years Ago. Tea and Antipathy by Frederic D. Schwarz». American Heritage Volume 48. 1997. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ Sutherland, L. (1952), pp. 249–251

- ^ Clapham, J. (1944) The Bank of England, p. 250

- ^ Mitchell, Stacy. The big box swindle. Archived from the original on 21 July 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ Robins, Nick (2012), «A Skulking Power», The Corporation That Changed the World, How the East India Company Shaped the Modern Multinational, Pluto Press, pp. 171–198, doi:10.2307/j.ctt183pcr6.16, ISBN 978-0-7453-3195-9, JSTOR j.ctt183pcr6.16, archived from the original on 3 February 2021, retrieved 30 January 2021

- ^ East India Stock Dividend Redemption Act 1873 (36 & 37 Vict. 17) s. 36: «On the First day of June One thousand eight hundred and seventy-four, and on payment by the East India Company of all unclaimed dividends on East India Stock to such accounts as are herein-before mentioned in pursuance of the directions herein-before contained, the powers of the East India Company shall cease, and the said Company shall be dissolved.» Where possible, the stock was redeemed through commutation (i.e. exchanging the stock for other securities or money) on terms agreed with the stockholders (ss. 5–8), but stockholders who did not agree to commute their holdings had their stock compulsorily redeemed on 30 April 1874 by payment of £200 for every £100 of stock held (s. 13).

- ^ Foster, Sir William (1924). The East India House: its History and Associations. London: John Lane.

- ^ Hobhouse, Hermione, ed. (1994). «Blackwall Yard». Poplar, Blackwall and Isle of Dogs: the parish of All Saints. Survey of London. Vol. 44. London: Athlone Press/Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England. pp. 553–565. ISBN 9780485482447. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020 – via British History Online.

- ^ Hobhouse, Hermione, ed. (1994). «The East India Docks». Poplar, Blackwall and Isle of Dogs: the parish of All Saints. Survey of London. Vol. 44. London: Athlone Press/Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England. pp. 575–582. ISBN 9780485482447. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020 – via British History Online.

- ^ Danvers, Frederick Charles; Martineau, Harriet; Monier-Williams, Monier; Bayley, Steuart Colvin; Wigram, Percy; Sapte, Brand (1894). Memorials of Old Haileybury College. Westminster: Archibald Constable.

- ^ a b Farrington 1976.

- ^ Vibart, H. M. (1894). Addiscombe: its heroes and men of note. Westminster: Archibald Constable. OL 23336661M.

- ^ Farrington 1976, pp. pp. 111–23.

- ^ Farrington 1976, pp. 125–132.

- ^ Bolton, Diane K.; Croot, Patricia E. C.; Hicks, M. A. (1982). «Ealing and Brentford: Public services». In Baker, T. F. T.; Elrington, C. R. (eds.). A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 7, Acton, Chiswick, Ealing and Brentford, West Twyford, Willesden. London: Victoria County History. pp. 147–149.

- ^ «East India Club». Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ^ Forrest, Denys Mostyn (1982). Foursome in St James’s: the story of the East India, Devonshire, Sports, and Public Schools Club. London: East India, Devonshire, Sports and Public Schools Club.

- ^ Fawcett, Charles (30 July 2013). Rob Raeside (ed.). «The Striped Flag of the East India Company, and its Connexion with the American «Stars and Stripes»«. Archived from the original on 18 June 2003. Retrieved 26 September 2003.

- ^ a b «East India Company». Hubert Herald. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- ^ East India Company coin 1791, half pice, as illustrated.

- ^ «Scinde District Dawks». 27 October 2009. Archived from the original on 27 October 2009.

- ^ Sutton, Jean (1981) Lords of the East: The East India Company and Its Ships. London: Conway Maritime

- ^ «Dictionary & Glossary». India Office Family History Search. British Library. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ Anderson, Ross (2014). «New source for EIC vessel and crew lost on the Western Australian coast». The Great Circle. Australian Association for Maritime History. 36 (1): 33–38. ISSN 0156-8698. JSTOR 24583017. Archived from the original on 5 August 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ «The Discovery Service». discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ Farrington, Anthony, ed. (1999). Catalogue of East India Company ships’ journals and logs: 1600–1834. London: British Library. ISBN 978-0-7123-4646-7.

- ^ The Emergence of International Business, 1200–1800: The English East India Company. p. Appendix.

Further reading[edit]

- Andrews, Kenneth R. (1985). Trade, Plunder, and Settlement: Maritime Enterprise and the Genesis of the British Empire, 1480–1630. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-25760-2.

- Bowen, H. V. (1991). Revenue and Reform: The Indian Problem in British Politics, 1757–1773. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-40316-0.

- Bowen, H. V. (2003). Margarette Lincoln; Nigel Rigby (eds.). The Worlds of the East India Company. Rochester, NY: Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85115-877-8.; 14 essays by scholars

- Brenner, Robert (1993). Merchants and Revolution: Commercial Change, Political Conflict, and London’s Overseas Traders, 1550–1653. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05594-7.

- Carruthers, Bruce G. (1996). City of Capital: Politics and Markets in the English Financial Revolution. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-04455-2.

- Chaudhuri, K. N. (1965). The English East India Company: The Study of an Early Joint-Stock Company, 1600–1640. London: Cass.

- Chaudhuri, K. N. (1978). The Trading World of Asia and the English East India Company, 1660–1760. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-21716-3.

- Chaudhury, S. (1999). Merchants, Companies, and Trade: Europe and Asia in the Early Modern Era. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Collins, G. M. (2019). «The Limits of Mercantile Administration: Adam Smith and Edmund Burke on Britain’s East India Company» Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 41(3), 369–392.

- Dalrymple, William (March 2015). The East India Company: The original corporate raiders Archived 26 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine. «For a century, the East India Company conquered, subjugated and plundered vast tracts of south Asia. The lessons of its brutal reign have never been more relevant.» The Guardian

- William Dalrymple The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company, Bloomsbury, London, 2019, ISBN 978-1-4088-6437-1.

- Dirks, Nicholas (2006). The Scandal of Empire: India and the creation of Imperial Britain. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02166-2.

- Dann, John (2019). Mr Bridgman’s Accomplice -Long Ben’s Coxswain 1660–1722. ISBN 978-178456-636-4.

- Dodwell, Henry. Dupleix and Clive: Beginning of Empire. (1968).

- Dulles, Foster Rhea (1931). Eastward ho! The first English adventurers to the Orient (1969 ed.). Freeport, New York: Books for Libraries Press. ISBN 978-0-8369-1256-2. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Farrington, Anthony (2002). Trading Places: The East India Company and Asia, 1600–1834. London: British Library. ISBN 978-0-7123-4756-3.

- Finn, Margot; Smith, Kate, eds. (2018). The East India Company at Home, 1757–1857. London: UCL Press. ISBN 978-1-78735-028-1.

- Furber, Holden. John Company at Work: A study of European Expansion in India in the late Eighteenth century (Harvard University Press, 1948)

- Furber, Holden (1976). Rival Empires of Trade in the Orient, 1600–1800. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-0787-7.

- Gardner, Brian. The East India Company : a history (1990) Online free to borrow

- Greenwood, Adrian (2015). Victoria’s Scottish Lion: The Life of Colin Campbell, Lord Clyde. UK: History Press. p. 496. ISBN 978-0-7509-5685-7. Archived from the original on 27 November 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- Harrington, Jack (2010), Sir John Malcolm and the Creation of British India, New York: Palgrave Macmillan., ISBN 978-0-230-10885-1

- Hutková, K. (2017). «Technology transfers and organization: the English East India Company and the transfer of Piedmontese silk reeling technology to Bengal, 1750s–1790s» Enterprise & Society, 18(4), 921–951.

- Keay, John (2010). The Honourable Company: A History of the English East India Company. HarperCollins UK. ISBN 978-0-00-739554-5. Archived from the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- Kumar, Deepak. (2017) The evolution of colonial science in India: natural history and the East India Company.» Imperialism and the natural world (Manchester University Press, 2017).

- Lawson, Philip (1993). The East India Company: A History. London: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-07386-9. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- Leinwand, Theodore B. (2006). Theatre, Finance and Society in Early Modern England. Cambridge University. ISBN 978-0-521-03466-1.

- McAleer, John. (2017). Picturing India: People, Places, and the World of the East India Company (University of Washington Press).

- MacGregor, Arthur (2018). Company Curiosities: nature, culture and the East India Company, 1600–1874. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 9781789140033.

- Marshall, P. J. Problems of Empire: Britain and India 1757–1813 (1968) Online free to borrow

- Misra, B. B. The Central Administration of the East India Company, 1773–1834 Archived 12 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine (1959)

- Mottram, R. H. (1939). Trader’s Dream: The Romance of the [British] East India Company. New York: D. Appleton-Century.

- O’Connor, Daniel (2012). The Chaplains of the East India Company, 1601–1858. London: Continuum. ISBN 978-1-4411-7534-2.

- Oak, Mandar, and Anand V. Swamy. «Myopia or strategic behavior? Indian regimes and the East India Company in late eighteenth century India.» Archived 26 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine Explorations in economic history 49.3 (2012): 352–366.

- Philips, C. H. The East India Company 1784–1834 (2nd ed. 1961), on its internal workings.

- Raman, Bhavani. «Sovereignty, property and land development: the East India Company in Madras.» Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 61.5–6 (2018): 976–1004.

- Rees, L. A. (2017). Welsh sojourners in India: the East India Company, networks and patronage, c. 1760–1840. Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 45(2), 165–187.

- Riddick, John F. The history of British India: a chronology Archived 14 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine (2006), covers 1599–1947

- Riddick, John F. Who Was Who in British India (1998), covers 1599–1947

- Ruffner, Murray (21 April 2015). «Selden Map Atlas». Thinking Past. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- Risley, Sir Herbert H., ed. (1908), The Indian Empire: Historical, Imperial Gazetteer of India, vol. 2, Oxford: Clarendon Press, under the authority of H.M. Secretary of State for India

- Risley, Sir Herbert H., ed. (1908), The Indian Empire: Administrative, Imperial Gazetteer of India, vol. 4, Oxford: Clarendon Press, under the authority of H.M Secretary of State for India

- Robins, Nick (December 2004). The world’s first multinational Archived 24 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine, in the New Statesman

- Robins, Nick (2006). The Corporation that Changed the World: How the East India Company Shaped the Modern Multinational. London: Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-2524-8.

- Sen, Sudipta (1998). Empire of Free Trade: The East India Company and the Making of the Colonial Marketplace. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-3426-8.

- Sharpe, Brandon (23 April 2015). «Selden Map Atlas». Thinkingpast.com. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- St. John, Ian. The Making of the Raj: India Under the East India Company Archived 20 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine (ABC-CLIO, 2011)

- Steensgaard, Niels (1975). The Asian Trade Revolution of the Seventeenth Century: The East India Companies and the Decline of the Caravan Trade. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-77138-0.

- Stern, Philip J. The Company-State: Corporate Sovereignty and the Early Modern Foundations of the British Empire in India Archived 23 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine (2011)

- Sutherland, Lucy S. (1952). The East India Company in Eighteenth-Century Politics. Oxford: Clarendon Press. (also): «The East India Company in Eighteenth-Century Politics.» Economic History Review 17.1 (1947): 15–26. online Archived 14 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Vaughn, J. M. (2019). The Politics of Empire at the Accession of George III: The East India Company and the Crisis and Transformation of Britain’s Imperial State (Lewis Walpole Series in Eighteenth-Century Culture and History).

- Williams, Roger (2015). London’s Lost Global Giant: In Search of the East India Company. London: Bristol Book Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9928466-2-6.

Historiography[edit]

- Farrington, Anthony, ed. (1976). The Records of the East India College, Haileybury, & other institutions. London: H.M.S.O.

- Stern, Philip J. (2009). «History and historiography of the English East India Company: Past, present, and future!». History Compass. 7 (4): 1146–1180. doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2009.00617.x.

- Van Meersbergen, G. (2017). «Writing East India Company History after the Cultural Turn: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on the Seventeenth-Century East India Company and Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie.» Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies, 17(3), 10–36. online Archived 28 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine

External links[edit]

- Charter of 1600

- East India Company on In Our Time at the BBC

- Seals and Insignias of East India Company

- The Secret Trade The basis of the monopoly.

- Trading Places – a learning resource from the British Library

- Port Cities: History of the East India Company

- Ships of the East India Company

- Plant Cultures: East India Company in India

- History and Politics: East India Company

- Nick Robins, «The world’s first multinational», 13 December 2004, New Statesman

- East India Company: Its History and Results article by Karl Marx, MECW Volume 12, p. 148 in Marxists Internet Archive

- Text of East India Company Act 1773

- Text of East India Company Act 1784

- «The East India Company – a corporate route to Europe» on BBC Radio 4’s In Our Time featuring Huw Bowen, Linda Colley and Maria Misra

- HistoryMole Timeline: The British East India Company

- William Howard Hooker Collection: East Indiaman Thetis Logbook (#472-003), East Carolina Manuscript Collection, J. Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University

Одна из крупнейших и доминирующих корпораций в истории действовала задолго до появления таких технологических гигантов, как Apple, Google или Amazon. Английская Ост-Индская компания была учреждена королевской хартией 31 декабря 1600 г.

Она получала огромные прибыли от внешней торговли с Индией, Китаем, Персией и Индонезией на протяжении более двух веков. Ее бизнес наводнил Англию доступным чаем, хлопчатобумажными тканями и специями. И щедро вознаградил своих лондонских инвесторов доходностью.

На пике своего развития Британская Ост-Индская компания являлась, безусловно, самой крупной частной компанией в мире. Ее бюджет также был больше, чем у некоторых стран. Но когда в конце 18 века влияние Ост-Индской компании на торговлю ослабло, она нашла новое призвание в качестве строителя империи. В какой-то момент эта мега-корпорация командовала частной армией из 260 000 сотрудников, что превышало размер армий многих европейских стран.

Без Ост-Индской компании в Индии в XIX и XX веках не было бы имперского британского владычества. И безумный успех первой в мире транснациональной корпорации помог сформировать современную глобальную экономику.

Основание Ост-Индской компании

В последний день 1600 года королева Елизавета I дала объединению английских купцов монопольные права на зарубежную торговлю с Ост-Индией. Огромной частью земного шара, простирающейся от африканского мыса Доброй Надежды на восток до мыса Горн в Южной Америке. Новообразованная компания была монополией в том смысле, что никакие другие британские торговцы не могли законно торговать на этой территории. Однако это не избавило ее от жесткого соперничества со стороны Испании и Португалии. У которых уже были торговые представительства в Индии, а также Голландской Ост-Индской компании, основанной в 1602 году.

Англия, как и остальная часть Западной Европы, испытывала аппетит к экзотическим восточным товарам, таким как специи, ткани и украшения. Но морские путешествия в Ост-Индию были чрезвычайно рискованными предприятиями, которые включали вооруженные столкновения с конкурирующими торговцами и смертельные заболевания, такие как цинга. Уровень смертности сотрудников Ост-Индской компании был шокирующим – 30 процентов.

Многие отличительные черты современной корпорации были впервые применены Ост-Индской компанией. Например, это была крупнейшая и самой продолжительная акционерная компания своего времени. Она привлекала и объединяла капитал путем продажи акций населению.

Потребительская культура, питаемая торговлей в Ост-Индии

До Ост-Индской компании большая часть одежды в Европе была сделана из шерсти. И рассчитана на долговечность, а не на моду. Но это начало меняться, поскольку рынки наводнили недорогие, красиво сотканные хлопчатобумажные ткани из Индии. Где каждый регион страны производил ткань разных цветов и узоров. Новые ткани внезапно стали модным на улицах городов Европы.

В Индии торговля и политика смешиваются

Когда британские и другие европейские торговцы прибыли в Индию, им пришлось искать расположение местных правителей и королей. Хотя Ост-Индская компания технически была частным предприятием. Ее устав и готовые к бою сотрудники придавали ей политический вес. Индийские правители приглашали боссов местной компании в суд. Вымогали у них взятки и использовали силы компании в региональных войнах. Иногда против французских или голландских торговых компаний.

От торговой компании к империи

Важный поворотный момент в превращении Ост-Индской компании из высокодоходной компании в полноценную империю наступил после битвы при Плесси в 1757 году. В битве 50 000 индийских солдат противостояли всего лишь 3 000 солдат компании. Победа дала Ост-Индской компании широкие налоговые преференции в Бенгалии. В то время одной из богатейших индийских провинций.

В 1784 году британский парламент принял «Закон об Индии». Который официально включал британское правительство в управление земельными владениями Ост-Индской компании в Индии. Когда это произошло, Компания перестала быть просто значительной торговой организацией. И стала частью настоящей Британской империи.

Опиумные войны и конец Ост-Индской компании

Интересы Ост-Индской компании не заканчивались в Индии. Одном из самых мрачных эпизодов в истории компании стал провоз контрабандой опиума в Китай в обмен на самый ценный товар страны – чай. Китай обменивал чай только на серебро, но его было трудно найти в Англии. Поэтому компания нарушила запрет Китая на поставку опиума через черный рынок индийских производителей и контрабандистов опиума. По мере того, как чай хлынул в Лондон, инвесторы компании разбогатели. А миллионы китайцев пропали в опиумных притонах.

Когда Китай начал подавлять торговлю опиумом, британское правительство направило военные корабли. Что спровоцировало Опиумную войну 1840 года. Унизительное поражение Китая передало Британии контроль над Гонконгом. Но конфликт пролил свет на темные дела Ост-Индской компании ради прибыли.

К середине XIX века противодействие монопольному статусу Ост-Индской компании достигла в английском парламенте апогея. Подпитываемого аргументами Адама Смита о свободном рынке.