Место.

На официальных географических картах США, территории под названием Кремниевая (или Силиконовая) долина не существует. Тем не менее, пожалуй, любой уважающий себя бизнесмен, венчурный инвестор или стартарпер в мире наверняка ответит, что такое место есть, находится оно в штате Калифорния США и является ведущим мировым центром притяжения для разработчиков высокотехнологических проектов или местом развития мировых инноваций.

Под Кремниевой долиной подразумевают территорию — место, где накоплен уникальный опыт создания и продвижения высокотехнологичных, наукоемких стартапов, лучшую в мире площадку, на которой, вот уже более полувека успешно взаимодействуют венчурные инвесторы, разработчики, стартарперы, представители ведущих мировых технологических компаний и деловых СМИ.

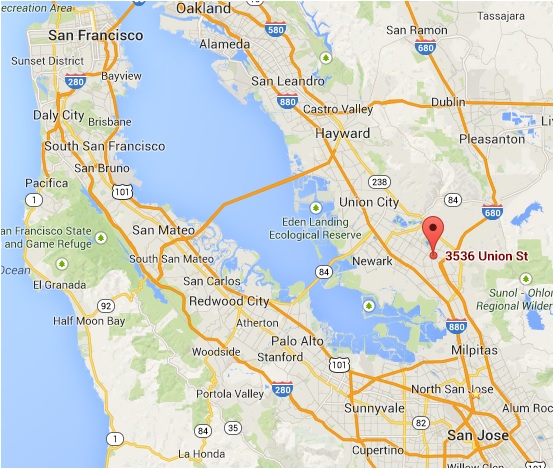

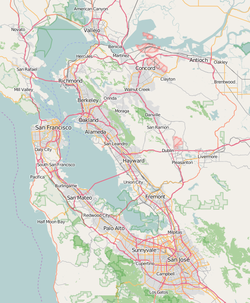

Изначально, под понятием «Кремниевая долина» подразумевали территорию находящуюся примерно в 20 милях от Сан-Франциско в районе пяти малых городов — Пало-Альто, Саннинвейл, Маутен-Вью, Купертино, и Санта-Клара. В настоящее время Кремниевой долиной считается куда более обширная территория от Сан-Франциско до Сан-Хосе включительно. Кремниевая долина сегодня это северная часть долины Санта-Клара, частично полуостров Сан-Франциско, восточный берег залива Сан-Франциско, туда же можно включить Кэмпбелл, Белмонт, Сан-Мантео, Поло-Альто, Фримонт, Лос-Алтос, Лос-Гатос, Менло-Парк, Милпитас, Морган Хил, Редвуд-Сити, Саратога, местность между хребтами Рашен-Ридж, Монте-Белло и Береговым хребтом ограниченную горами Койот-Пик, а так же долины Вест, Алмаден, Энергин, Палм и Мишен. В какой то мере, туда же можно отнести Санта-Круз, Скотс-Валли, Ливермор и Плезантон. Центром или неофициальной столицей Кремниевой долины принято считать Сан-Хосе.

История Кремниевой долины.

По всей видимости, история Кремниевой долины берет свое начало в 1951г. в Стэдфордском индустриальном парке, который создавался на землях Стэнфордского университета передаваемых им в долгосрочную аренду (до 99 лет) высокотехнологическим компаниям.

Первыми резидентами нового инновационного центра стали — Varian Associates, Hewlett-Paskard, Eastman Kodak, General Electric, Lockheed Corporation, другие высокотехнологические компании и стартапы.

Меньше полувека назад, в 1971г. понятие «Кремниевая долина» стало входить в мировой обиход с легкой руки журналиста Дона Хефлера, который использовал его первым в рамках серии статей под названием — Кремниевая долина США.

Не стоит путать понятия «Кремниевая долина» и «Силиконовая долина», как то связывая их между собой. Поскольку Silicon Valley (Кремниевая долина) находится в Калифорнии, а Silicone Valley (Силиконовая долина) или долина Сан-Фернандо, является другим знаковым-злаковым местом в США, где снимается большинство порнофильмов.

Самым первым, глобальным и успешным проектом Кремниевой долины стал Hewlet-Packard. В настоящее время компания является одним из мировых лидеров в области производства персональных компьютеров и других периферийных устройств.

Инфраструктура Кремниевой долины.

Основа — штат Калифорния (столица Сакраменто), крупнейшие города — Лос-Анжелес, Сан-Франциско, Сан-Хосе, Окленд, Сан-Диего, Сан-Бернардино, Риверсайд. Калифорния занимает первое место среди штатов США по объему валового продукта — более 2 трлн. долл., что сопоставимо с ВВП всей Российской Федерации за 2014г. (номинальный ВВП РФ в 2014г. составил 1,861 трлн. долл., по ППС — 3,745 трлн. долл.). В Калифорнии проживает больше всего миллиардеров — около 80-ти из списка Forbes 400. Калифорния является самым населенным штатом в Америке — 38,4 млн. чел., которые проживают в 480 городах и в сельской местности. Штат занимает третье место по площади в США.

Климат — средиземноморский, относительно прохладное лето и теплая зима, большое количество солнечных дней в году.

Крупнейшими городами в Кремниевой долине являются — Сан-Франциско, Сан-Хосе, Сан-Мантео, Поло-Альто, Фримонт, Санта-Круз, Скотс-Валли, Ливермор и Плезантон.

Инфраструктура — Кремниевая долина входит в тройку крупнейших технологических центров США (совместно с подобными центрами в Нью-Йорке и Вашингтоне).

Интелектуальное ядро — Стэнфордский университет, частный иследовательский университет, один из самых престижных в мире и высоко котирующихся в академических рейтингах вузов США и мира. Располагается южнее Сан-Франциско, рядом с Поло-Альто. Стэнфорд ежегодно принимает в свои ряды около 7000 студентов и 8000 аспирантов. Многие из выпускников впоследствии пополняют ряды обитателей Кремниевой долины, работая в местных компаниях, иногда возглавляют их или инициируют собственные проекты и стартапы, некоторые из которых, становятся успешными компаниями, самые успешные – глобальными компаниями мирового уровня. Сюда же, можно отнести университет Сан–Хосе (обучается около 30 000 студентов, до 130 образовательных программ) и университет Санта–Клары (старейший частный университет штата), а также Калифорнийский университет в Санта–Крузе (один из объединения 10-ти публичных калифорнийских университетов (самый известный – университет Беркли)).

Компании Кремниевой долины.

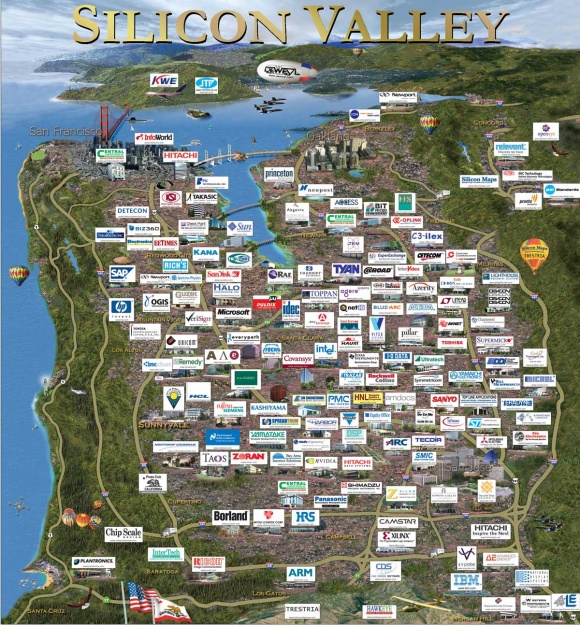

В настоящий момент около трех тысяч предприятий располагают свои головные офисы, представительства, центры разработки или производства в Кремниевой долине. Более трехсот компаний связаны с выпуском компьютеров, более тысячи занимаются созданием программного обеспечения.

Пионеры, родоначальники, самые успешные компании Кремниевой долины:

Varian Associates – один из пионеров СВЧ технологий. Первыми заключили договор аренды со Стенфордским университетом в 1951г., а в 1953г. въехали в уже построенный офис в Кремниевой долине.

Hewlett–Packard – Hewlett – Packard Company (HP). Пожалуй, первая успешная глобальная транснациональная компания из Кремниевой долины. Информационные технологии, аппаратное и программное обеспечение, персональные и планшетные компьютеры, смартфоны, серверы, устройства хранения данных, сетевое оборудование, принтеры, сканеры и т.п. Основана в 1939г. Штаб квартира в Поло – Альто. Одна из самых дорогих компаний, торгуется на NYSE, тикер акций – HPQ.

Eastman Kodak – Eastman Kodak Со. (США). Первая компания, создавшая цифровой фотоаппарат. Основана в 1881г. В 2013г. завершила процедуру банкротства. Торгуется на NYSE, символ акций – EК.

General Electric – General Electric (CША). Глобальная, многоотраслевая корпорация, производство – электротехнического, энергетического, медицинского оборудования, бытовой техники, транспортное машиностроение, авиадвигатели, др. Создана 1978г. Торгуется на NYSE, тикер акций – GE.

Lockheed Corporation – Lockheed Martin Corporation (США). Глобальная компания, работает в оборонной и в авиа–космической отрасли, основной заказчик и потребитель правительство США. Основана в 1912г. Расположена в Бербанк (Калифорния). Торгуется на NYSE, символ акций – LMT.

Intel – intel Corporation. (США). Производитель электронных устройств и компьютерных компонентов – микропроцессоров, флэш–памяти, SSD–накопители, сетевое оборудование, серверы, чипсеты. Создана в 1968г. Штаб–квартира в Санта – Клара. Торгуется на NASDAQ, тикер акций – INTC.

Apple – Apple Ink. (США). Производство ПК, планшетных компьютеров, аудиоплееров, телефонов и программного обеспечения – лидер индустрии. Основана в 1976г. Штаб квартира в Купертино. Одна из самых дорогих компаний, торгуется на NASDAQ, символ акций – AAPL.

Крупнейшие компании, входящие или входившие в разное время в ТОП Fortune 1000 располагающие свои офисы в Кремниевой долине.

Adobe — Adobe Systems, Incorporated. (США). Разработка программного обеспечения. Основана в 1982г. Офис в Сан–Хосе. Торгуется на NASDAQ, тиккер акций – ADBE.

AMD – Advanced Micro Devices, Inc. (США). Производство микрочипов, процессоров, графических процессоров, чипсетов и флэш– памяти. Создана в 1969г. Офис в Саннинвейл. Торгуется на NYSE, символ акций – AMD.

Altera — Аltera. (США). Разработчик логистических интегральных схем. Основана в 1983г. Основана в 1983г. Офис в Сан–Хосе. Включена в индекс S&P 500, торгуется на NASDAQ, тикер акций – ALTR.

Cisco – Cisco Systems, Inc. (США). Разработка и продажа сетевого оборудования. Создана в 1984г. Офис в Сан–Хосе. Торгуется на NASDAQ, символ акций – CSCO.

еВау – еВау Inc. (США). Услуги интернет аукциона, интернет магазина и осуществления мгновенных платежей (владеет PayPal). Основана в 1995г. Офис в Сан–Хосе. Торгуется на NASDAQ, тикер акций – EBAY.

Electronic Arts – Electronic Arts (EA). (США). Разработка, производство и распространение видеоигр, пионер рынка. Основана в 1982г. Штаб квартира в Редвуде. Торгуется на NASDAQ, символ акций – ЕА.

Facebook – Facebook. (CША). Крупнейшая социальная сеть в мире. Основана в 2004г. Штаб–квартира в Пало–Альто, Менло–Парк. Торгуется на NASDAQ, тикер акций – FB.

Google – Google, Inc. (CША). Крупнейший в мире интернет поисковик, облачные и рекламные технологии в интернете. Создана в 1998г., выход на биржу в 2004г. Штаб–квартира в Маутин–Вью. Торгуется на NASDAQ, символ акций – GOOG.

NetApp – NetApp, Inc. (США). Разработка и производство дисковых систем, и решений для хранения данных и управления информацией. Основана в 1992г. Штаб – квартира в Саннинвейл. Торгуется на NASDAQ, тикер акций – NTAP.

Nvidia – NVIDIA Corporation. (США). Разработка графических ускорителей и процессоров. Создана в 1993г. Офис в Санта – Клара. Торгуется на NASDAQ, символ акций – NVDA.

Оracle – Oracle. (CША). Производство программного обеспечения, поставки серверного оборудования. Основана в 1977г. Штаб квартира в Рэдвуд Шорз, южнее Сан – Франциско. Торгуется на NASDAQ, тикер акций – ORCL.

SanDisc – SanDisk. (CША). Крупнейший в мире разработчик и производитель носителей информации, карт памяти на базе флэш – памяти. Создана в 1988г. Офис в Милпитас. Торгуется на NASDAQ, символ акций – SNDK.

Symantec – Symantec. Разработка программного обеспечения в области информационной безопасности и её защиты, а так же программного обеспечения для ПК и центров обработки данных. Основана в 1982г. Офис в Купертино. Торгуется на NASDAQ, тикер акций – SYMC.

Yahoo! – Yahoo! (США). Вторая по популярности поисковая система в мире. Создана в 1995г. Офис в Саннинвейл. Торгуется на NASDAQ, символ акций – YHOO.

Хerox – Хerox Corporation. (США). Производство офисной, компьютерной и бытовой техники. Основана в 1906г. Торгуется на NYSE, тикер акций – XRX.

Tesla Motors – Tesla Motors. (CША). Производство электромобилей, создание инфраструктуры (сети станций подзарядки) для электромобилей. Основана в 2003г. Офис в Поло – Альто. Торгуется на NASDAQ, символ акций – TSLA.

Самые знаковые люди Кремниевой долины.

Фредерик Эммонс Терман – профессор Стэнфордского университета, (сын Льюса Термана создателя IQ теста), которого многие считают отцом и идеологом и одним из первых «бизнес ангелов» Кремниевой долины. В 1951г. возглавил работу по созданию Стэнфордского индустриального парка, на землях переданных университетом для размещения высоко технологических компаний. На протяжении нескольких десятков лет участвовал в становлении и формировании главного бизнес инкубатора в мире. Поощрял своих студентов создавать собственные компании, в некоторые из которых он инвестировал собственные средства.

Уильям Шокли – лауреат Нобелевской премии 1956г. по физике. Изобрел плоскостной биполярный транзистор, руководил одной из первых лабораторий в Кремниевой долине. Инициатор и участник многочисленных скандалов, был не так удачлив, как многие из его бывших партнеров и сотрудников, которые уходя от него, запускали собственные успешные стартапы и создавали компании, в частности так возникли – Fairchild Semiconductor, Intel и многие другие проекты, в общей сложности более ста компаний.

Уильям Миллер – профессор менеджмента и компьютерных наук Стенфордского университета. Основатель нескольких успешных стартапов и компаний, один из организаторов сетевого предпринимательского сообщества Joint Venture Silicon Valley Netvork в Кремниевой долине. При этом свою первую компанию он открыл в 60 лет!

Самые успешные предприниматели Кремниевой долины – Билл Хьюлетт, Дейв Паккард (Hewlett–Packard), Гари Хендрикс (Symantec), Гордон Мур, Робберт Нойс и Энди Гроув (Intel), Ларри Эллисон (Oracle), Стив Джобс и Стив Возняк (Apple), Билл Гейтс (Microsoft), Пьер Омидьяр (еВау), Джерри Янг и Дэвид Файло (Yahoo!), Ларри Пейдж и Сергей Брин (Google), Эван Уильямс, Джек Дорси, Биз Стоун и Ноа Гласс (Twitter), Марк Цукерберг (Facebook), Илон Маск (РаyPal, Tesla Motors, SpaceX) и многие, многие другие.

Самые успешные предприниматели Кремниевой долины, выходцы из бывшего СССР и России – Сергей Брин (Google), Ян Кум (WhatsApp), Валентин Гапонцев (IPG Photonics), Юрий Мильнер (инвестор – Facebook, Zynga, Twitter, Spotify, Groupon и др.), Макс Левчин (PayPal), Сергей Белоусов (Parallels и Acronis), Григорий Шенкман и Алекc Милославский (Genesys Telecommunications Labaratories и Exigen Services), Степан Пачиков (ParaGraph и Evernote), Давид Ян (ABBYY, программы Fine Reader и Lingvo), Юрий Фрайман (Viewdle) и многие другие. *(По разным оценкам от 30 000 до 60 000 специалистов и членов их семей проживающих в Кремниевой долине являются выходцами из России.

Кремниевая долина входит в тройку крупнейших технологических центров США (вместе с Нью–Йорком и Вашингтоном), всего там трудится около 400 000 специалистов ИТ–сферы. На каждую 1000 работников долины приходится порядка 300 специалистов IT–отрасли. Около 40% всех инженеров США работающих в области электроники, информатики и вычислительной техники работают в Калифорнии.

В школах Кремниевой долины процент детей имеющих высший коэффициент интеллектуальных способностей, измеряемых по принятым в США методикам, кратно превышает средний показатель по стране.

Основные факторы успеха Кремниевой долины:

1.Открытость, демократичность, акцент на горизонтальные связи, отсутствие вертикальных органов управления.

2.Дух творчества, инновационность и креативность.

3.Доступность научных ресурсов, технологий и разработок.

4.Развитые коммуникации и высокий уровень сотрудничества и кооперации не смотря на высочайший уровень конкуренции.

5.Высочайшая, активность, мотивация и ориентированность на успех всех обитателей Кремниевой долины.

6.Наличие хорошо отработанной технологии продвижения стартапов начиная с посевной стадии, венчурное и промежуточное финансирование, до вывода наиболее успешных компаний на IPO.

7.Ориентация на глобальные рынки, новые, прорывные и перспективные технологии.

8.Удачное местонахождение – в США с крупнейшей мировой экономикой и в штате Калифорния – одном из богатейших штатов Америки.

9.Минимальное государственного регулирование, хорошее законодательство, протекционизм, высокая скорость согласований, отсутствие засилья чиновников. Капитал и бизнес принимают основные решения и правят бал.

10.Кремниевая долина сумела привлечь крупнейших в мире инвесторов, лучших менторов, самых амбициозных бизнесменов и предпринимателей, ученых, а так же наиболее квалифицированных специалистов и работников.

36:46 Силиконовая Долина — большие возможности!

Конкуренты, аналоги и подражатели Кремниевой долины – крупнейшие технологические парки, бизнес инкубаторы и инновационные центры мира.

Нью–Йорк, штат Нью – Йорк, США. Кремниевая аллея – трехмильная полоса земли, простирающаяся от квартала Челси до его южной оконечности.

Бостон, штат Массачусетс, США. Территория вдоль дороги 128 – «Восточная кремниевая долина».

Остин, штат Техас, США. Резиденты – более 2000 хай–тек компаний.

Солт–Лейк–Сити, штат Юта, США. Основные резиденты хай–тек компании.

Кембридж, Великобритания. Технопарк вокруг Кембриджского университета.

Мedicon Valley, Дания и Швеция (Копенгаген и Мальме) – крупнейший в Европе технологический парк. Основные направления – медицина, биотехнологии, пищевое производство, другие отрасли. В сфере разработок занято более 40 000 сотрудников и 4 000 ученых.

Телль – Авив, Израиль. Размещаются многие крупнейшие в мире хай–тек и телекоммуникационные компании.

Чжунгуаньцунь, Китай. Офисы и заводы Microsoft, IBM, Intel, Nokia и других мировых гигантов, зарегистрировано более 20 000 компаний с суммарной выручкой более 400 млрд. долл., обеспечивает занятость около 1 млн. работников.

Хсинчу, Тайвань. Располагаются многие крупнейшие азиатские и мировые компании производители полупроводников, компьютерной техники и других электронных устройств.

Бангалор, Индия – около 200 высших учебных заведений, является одним из мировых центров фармакалогии, биотехнологий, космических исследований, компьютерных технологий и аэронавтики, хотя начинал, как центр оффшорного программирования.

Сколково, Россия – Площадь отведенной территории 400 Га. Более подробно о проекте в другой статье: Сколково – промежуточные итоги и перспективы. utmagazine.ru/posts/10900-skolkovo-promezhutochnye-itogi-i-perspektivy

Informatics Valley, Турция – рядом со Стамбулом. Проект стартовал в одно время со Сколково в 2010г. Площадь отведенной территории 3000 Га. Планируется построить новый город для 150 000 жителей с научно – исследовательскими институтами, университетами, заводами по производству современного оборудования, больницами, спортивными сооружениями, детскими садами и школами.

Кремниевая долина — обратная сторона медали.

1.Количество провальных и неуспешных проектов многократно превышает количество успешных. Венчурный бизнес, по определению является «зоной рискового земледелия». Десяток, другой мега успешных глобальных проектов мирового уровня и даже сотня успешных проектов – всего лишь вершина айсберга. Кремниевая долина это не только Hewlett–Packard, Intel, Apple, Googl, Facebook и ряд других успешных проектов, но и сотни или даже тысячи провальных стартапов, за всю её историю. До 95% (19 из 20) стартапов Кремниевой долины, даже если они и получают инвестиции, не добиваются заметных успехов.

2.Стоимость жизни, жилья и социальной инфраструктуры – поскольку в Кремниевой долине существенно более высокий уровень зарплат и доходов, чем в среднем по стране, это влияет на уровень стоимости жизни, жилья и всего остального. Тем, кто только начинает свою карьеру в Кремниевой долине, приходится искать недорогое жилье на окраинах городов или в пригородах. То же самое можно сказать о медицинском обслуживании, детских садах, школах, общественном транспорте и т.п.

3.Кремниевая долина это мега-высоко конкурентная среда для всех её участников – инвесторов, бизнесменов, менторов, предпринимателей, стартарперов и наемных работников. Поэтому большая часть её обитателей вынуждена работать в условиях постоянного стресса, под угрозой провала или увольнения – больше и эффективней, чем во многих других местах США и мира. Психологические проблемы и проблемы со здоровьем становятся неизбежными спутниками многих участников этой ярмарки тщеславия и погони за успехом, которыми во многом, характеризуется деловой климат в Кремниевой долине. Две трети из опрошенных предпринимателей долины признают наличие семейных проблем, половина – психологических, треть – наличие депрессии, что в разы или многократно превышает средние показатели по США.

1:30 «Кремниевая долина» трейлер («Кубик в кубе»).

|

Silicon Valley |

|

|---|---|

|

From top, left to right: Aerial view of Silicon Valley; Stanford University in Stanford; Apple Park in Cupertino; Downtown San Jose; Mission Santa Clara de Asís in Santa Clara; and City Hall & Center for Performing Arts in Mountain View |

|

|

Silicon Valley |

|

| Coordinates: 37°22′39″N 122°04′03″W / 37.37750°N 122.06750°WCoordinates: 37°22′39″N 122°04′03″W / 37.37750°N 122.06750°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| Region | San Francisco Bay Area |

| Megaregion | Northern California |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

Silicon Valley is a region in Northern California that serves as a global center for high technology and innovation. Located in the southern part of the San Francisco Bay Area, it corresponds roughly to the geographical area of Santa Clara Valley.[1][2][3] San Jose is Silicon Valley’s largest city, the third-largest in California, and the tenth-largest in the United States; other major Silicon Valley cities include Sunnyvale, Santa Clara, Redwood City, Mountain View, Palo Alto, Menlo Park, and Cupertino. The San Jose Metropolitan Area has the third-highest GDP per capita in the world (after Zürich, Switzerland and Oslo, Norway), according to the Brookings Institution,[4] and, as of June 2021, has the highest percentage of homes valued at $1 million or more in the United States.[5]

Silicon Valley is home to many of the world’s largest high-tech corporations, including the headquarters of more than 30 businesses in the Fortune 1000, and thousands of startup companies. Silicon Valley also accounts for one-third of all of the venture capital investment in the United States, which has helped it to become a leading hub and startup ecosystem for high-tech innovation. It was in Silicon Valley that the silicon-based integrated circuit, the microprocessor, and the microcomputer, among other technologies, were developed. As of 2021, the region employed about a half million information technology workers.[6]

As more high-tech companies were established across San Jose and the Santa Clara Valley, and then north towards the Bay Area’s two other major cities, San Francisco and Oakland, the term «Silicon Valley» came to have two definitions: a narrower geographic one, referring to Santa Clara County and southeastern San Mateo County, and a metonymical definition referring to high-tech businesses in the entire Bay Area. The term Silicon Valley is often used as a synecdoche for the American high-technology economic sector. The name also became a global synonym for leading high-tech research and enterprises, and thus inspired similarly named locations, as well as research parks and technology centers with comparable structures all around the world. Many headquarters of tech companies in Silicon Valley have become hotspots for tourism.[7][8][9]

Etymology[edit]

«Silicon» refers to the chemical element used in silicon-based transistors and integrated circuit chips, which is the focus of a large number of computer hardware and software innovators and manufacturers in the region. The popularization of the name is credited to Don Hoefler.[1] The first known appearance in print was in his article «Silicon Valley U.S.A.», in the January 11, 1971, issue of the weekly trade newspaper Electronic News. In preparation for this report, during a lunch meeting with marketing people who were visiting the area, he heard them use this term.[10] However, the term did not gain widespread use until the early 1980s,[1] at the time of the introduction of the IBM PC and numerous related hardware and software products to the consumer market.

The urbanized area is built upon an alluvial plain[11] within a longitudinal valley formed by roughly parallel earthquake faults. The area between the faults subsided into a graben or dropped valley.[12][13] Hoefler defined Silicon Valley as the urbanized parts of «the San Francisco Peninsula and Santa Clara Valley».[10] Before the expansive growth of the tech industry, the region had been the largest fruit-producing and packing region in the world up through the 1960s, with 39 fruit canneries.[14][15] The nickname it had been known as during that period was «the Valley of Heart’s Delight»,[16][17]

History[edit]

Silicon Valley was born through the intersection of several contributing factors including a skilled science research base housed in area universities, plentiful venture capital, and steady U.S. Department of Defense spending. Stanford University leadership was especially important in the valley’s early development. Together these elements formed the basis of its growth and success.[18]

Early military origins[edit]

The Bay Area had long been a major site of United States Navy research and technology. In 1909, Charles Herrold started the first radio station in the United States with regularly scheduled programming in San Jose. Later that year, Stanford University graduate Cyril Elwell purchased the U.S. patents for Poulsen arc radio transmission technology and founded the Federal Telegraph Corporation (FTC) in Palo Alto. Over the next decade, the FTC created the world’s first global radio communication system, and signed a contract with the Navy in 1912.[19]

In 1933, Air Base Sunnyvale, California, was commissioned by the United States Government for use as a Naval Air Station (NAS) to house the airship USS Macon in Hangar One. The station was renamed NAS Moffett Field, and between 1933 and 1947, U.S. Navy blimps were based there.[20]

A number of technology firms had set up shop in the area around Moffett Field to serve the Navy. When the Navy gave up its airship ambitions and moved most of its west coast operations to San Diego, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA, forerunner of NASA) took over portions of Moffett Field for aeronautics research. Many of the original companies stayed, while new ones moved in. The immediate area was soon filled with aerospace firms, such as Lockheed, which was Silicon Valley’s largest employer from the 1950s into 1980s.[21]

Role of Stanford University[edit]

Stanford University played the central role in the emergence of Silicon Valley, both through its academic programs and through its real investments into the local tech ecosystem, such as with the Stanford Research Park.[22]

Stanford University, its affiliates, and graduates have played a major role in the development of this area.[22] A very powerful sense of regional solidarity accompanied the rise of Silicon Valley.[23] From the 1890s, Stanford University’s leaders saw its mission as service to the (American) West and shaped the school accordingly. At the same time, the perceived exploitation of the West at the hands of eastern interests fueled booster-like attempts to build self-sufficient local industry. Thus regionalism helped align Stanford’s interests with those of the area’s high-tech firms for the first fifty years[timeframe?] of Silicon Valley’s development.[24]

Frederick Terman, as Stanford University’s dean of the school of engineering from 1946,[25]

encouraged faculty and graduates to start their own companies. In 1951 Terman spearheaded the formation of Stanford Industrial Park (now Stanford Research Park, an area surrounding Page Mill Road, south west of El Camino Real and extending beyond Foothill Expressway to Arastradero Road), where the university leased portions of its land to high-tech firms.[26] Terman is credited[by whom?] with nurturing companies like Hewlett-Packard, Varian Associates, Eastman Kodak, General Electric, Lockheed Corporation, and other high-tech firms, until what would become Silicon Valley grew up around the Stanford University campus.

In 1951, to address the financial demands of Stanford’s growth requirements, and to provide local employment-opportunities for graduating students, Frederick Terman proposed leasing Stanford’s lands for use as an office park named the Stanford Industrial Park (later Stanford Research Park). Leases were limited[by whom?] to high-technology companies. The first tenant was Varian Associates, founded by Stanford alumni in the 1930s to build military-radar components. Terman also found venture capital for civilian-technology start-ups. Hewlett-Packard became one of the major success-stories. Founded in 1939 in Packard’s garage by Stanford graduates Bill Hewlett and David Packard, Hewlett-Packard moved its offices into the Stanford Research Park shortly after 1953. In 1954 Stanford originated the Honors Cooperative Program to allow full-time employees of the companies to pursue graduate degrees from the university on a part-time basis. The initial companies signed five-year agreements in which they would pay double the tuition for each student in order to cover the costs. Hewlett-Packard has become the largest personal-computer manufacturer in the world, and transformed the home-printing market when it released the first thermal drop-on-demand ink-jet printer in 1984.[27] Other early tenants included Eastman Kodak, General Electric, and Lockheed.[28]

Rise of Silicon[edit]

In 1956, William Shockley, the co-inventor of the first working transistor (with John Bardeen and Walter Houser Brattain), moved from New Jersey to Mountain View, California, to start Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory to live closer to his ailing mother in Palo Alto. Shockley’s work served as the basis for many electronic developments for decades.[29][30] Both Frederick Terman and William Shockley are often called «the father of Silicon Valley».[31][32] In 1953, William Shockley left Bell Labs in a disagreement over the handling of the invention of the bipolar transistor. After returning to California Institute of Technology for a short while, Shockley moved to Mountain View, California, in 1956, and founded Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory. Unlike many other researchers who used germanium as the semiconductor material, Shockley believed that silicon was the better material for making transistors. Shockley intended to replace the current transistor with a new three-element design (today known as the Shockley diode), but the design was considerably more difficult to build than the «simple» transistor. In 1957, Shockley decided to end research on the silicon transistor. As a result of Shockley’s abusive management style, eight engineers left the company to form Fairchild Semiconductor; Shockley referred to them as the «traitorous eight». Two of the original employees of Fairchild Semiconductor, Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore, would go on to found Intel.[33][34]

The first IBM plant in Silicon Valley, established in San Jose in 1943

In 1957, Mohamed Atalla at Bell Labs developed the process of silicon surface passivation by thermal oxidation,[35][36][37] which electrically stabilized silicon surfaces[38] and reduced the concentration of electronic states at the surface.[36] This enabled silicon to surpass the conductivity and performance of germanium, leading to silicon replacing germanium as the dominant semiconductor material,[37][39] and paving the way for the mass-production of silicon semiconductor devices.[40] This led to Atalla inventing the MOSFET (metal-oxide-silicon field-effect transistor), also known as the MOS transistor, with his colleague Dawon Kahng in 1959.[41] It was the first truly compact transistor that could be miniaturised and mass-produced for a wide range of uses,[42] and is credited with starting the silicon revolution.[39]

The MOSFET was initially overlooked and ignored by Bell Labs in favour of bipolar transistors, which led to Atalla resigning from Bell Labs and joining Hewlett-Packard in 1961.[43] However, the MOSFET generated significant interest at RCA and Fairchild Semiconductor. In late 1960, Karl Zaininger and Charles Meuller fabricated a MOSFET at RCA, and Chih-Tang Sah built a MOS-controlled tetrode at Fairchild. MOS devices were later commercialized by General Microelectronics and Fairchild in 1964.[41] The development of MOS technology became the focus of startup companies in California, such as Fairchild and Intel, fuelling the technological and economic growth of what would later be called Silicon Valley.[44]

Following the 1959 inventions of the monolithic integrated circuit (IC) chip by Robert Noyce at Fairchild, and the MOSFET (MOS transistor) by Mohamed Atalla and Dawon Kahng at Bell Labs,[41] Atalla first proposed the concept of the MOS integrated circuit (MOS IC) chip in 1960,[42] and then the first commercial MOS IC was introduced by General Microelectronics in 1964.[45] The development of the MOS IC led to the invention of the microprocessor,[46] incorporating the functions of a computer’s central processing unit (CPU) on a single integrated circuit.[47] The first single-chip microprocessor was the Intel 4004,[48] designed and realized by Federico Faggin along with Ted Hoff, Masatoshi Shima and Stanley Mazor at Intel in 1971.[46][49] In April 1974, Intel released the Intel 8080,[50] a «computer on a chip», «the first truly usable microprocessor».

Origins of the Internet[edit]

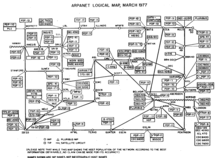

On April 23, 1963, J. C. R. Licklider, the first director of the Information Processing Techniques Office (IPTO) at The Pentagon’s ARPA issued an office memorandum addressed to Members and Affiliates of the Intergalactic Computer Network. It rescheduled a meeting in Palo Alto regarding his vision of a computer network, which he imagined as an electronic commons open to all, the main and essential medium of informational interaction for governments, institutions, corporations, and individuals.[51][52][53][54] As head of IPTO from 1962 to 1964, «Licklider initiated three of the most important developments in information technology: the creation of computer science departments at several major universities, time-sharing, and networking.»[54] In 1969, the Stanford Research Institute (now SRI International), operated one of the four original nodes that comprised ARPANET, predecessor to the Internet.[55]

Emergence of venture capital[edit]

By the early 1970s, there were many semiconductor companies in the area, computer firms using their devices, and programming and service companies serving both. Industrial space was plentiful and housing was still inexpensive. Growth during this era was fueled by the emergence of venture capital on Sand Hill Road, beginning with Kleiner Perkins and Sequoia Capital in 1972; the availability of venture capital exploded after the successful $1.3 billion IPO of Apple Computer in December 1980. Since the 1980s, Silicon Valley has been home to the largest concentration of venture capital firms in the world.[56]

In 1971, Don Hoefler traced the origins of Silicon Valley firms, including via investments from Fairchild’s eight co-founders.[10][57] The key investors in Kleiner Perkins and Sequoia Capital were from the same group, directly leading to Tech Crunch 2014 estimate of 92 public firms of 130 related listed firms then worth over US$2.1 trillion with over 2,000 firms traced back to them.[58]

Rise of computer culture[edit]

The Homebrew Computer Club was a highly influential computer hobbyist group in the 1970s and 80s that produced many influential tech founders, like Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak. Pictured is the invitation to its first meeting in 1975.

The Homebrew Computer Club was an informal group of electronic enthusiasts and technically minded hobbyists who gathered to trade parts, circuits, and information pertaining to DIY construction of computing devices.[59] It was started by Gordon French and Fred Moore who met at the Community Computer Center in Menlo Park. They both were interested in maintaining a regular, open forum for people to get together to work on making computers more accessible to everyone.[60]

The first meeting was held as of March 1975 at French’s garage in Menlo Park, San Mateo County, California; which was on occasion of the arrival of the MITS Altair microcomputer, the first unit sent to the area for review by People’s Computer Company. Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs credit that first meeting with inspiring them to design the original Apple I and (successor) Apple II computers. As a result, the first preview of the Apple I was given at the Homebrew Computer Club.[61] Subsequent meetings were held at an auditorium at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center.[62]

Advent of software[edit]

Although semiconductors are still a major component of the area’s economy, Silicon Valley has been most famous in recent years for innovations in software and Internet services. Silicon Valley has significantly influenced computer operating systems, software, and user interfaces.

Using money from NASA, the US Air Force, and ARPA, Douglas Engelbart invented the mouse and hypertext-based collaboration tools in the mid-1960s and 1970s while at Stanford Research Institute (now SRI International), first publicly demonstrated in 1968 in what is now known as The Mother of All Demos. Engelbart’s Augmentation Research Center at SRI was also involved in launching the ARPANET (precursor to the Internet) and starting the Network Information Center (now InterNIC). Xerox hired some of Engelbart’s best researchers beginning in the early 1970s. In turn, in the 1970s and 1980s, Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) played a pivotal role in object-oriented programming, graphical user interfaces (GUIs), Ethernet, PostScript, and laser printers.

While Xerox marketed equipment using its technologies, for the most part its technologies flourished elsewhere. The diaspora of Xerox inventions led directly to 3Com and Adobe Systems, and indirectly to Cisco, Apple Computer, and Microsoft. Apple’s Macintosh GUI was largely a result of Steve Jobs’ visit to PARC and the subsequent hiring of key personnel.[63] Cisco’s impetus stemmed from the need to route a variety of protocols over Stanford University’s Ethernet campus network.[64]

Internet age[edit]

Commercial use of the Internet became practical and grew slowly throughout the early 1990s. In 1995, commercial use of the Internet grew substantially and the initial wave of internet startups, Amazon.com, eBay, and the predecessor to Craigslist began operations.[65]

Silicon Valley is generally considered to have been the center of the dot-com bubble, which started in the mid-1990s and collapsed after the NASDAQ stock market began to decline dramatically in April 2000. During the bubble era, real estate prices reached unprecedented levels. For a brief time, Sand Hill Road was home to the most expensive commercial real estate in the world, and the booming economy resulted in severe traffic congestion.

The PayPal Mafia is sometimes credited with inspiring the re-emergence of consumer-focused Internet companies after the dot-com bust of 2001.[66] After the dot-com crash, Silicon Valley continues to maintain its status as one of the top research and development centers in the world. A 2006 The Wall Street Journal story found that 12 of the 20 most inventive towns in America were in California, and 10 of those were in Silicon Valley.[67] San Jose led the list with 3,867 utility patents filed in 2005, and number two was Sunnyvale, at 1,881 utility patents.[68] Silicon Valley is also home to a significant number of «Unicorn» ventures, referring to startup companies whose valuation has exceeded $1 billion dollars.[69]

Economy[edit]

The San Francisco Bay Area has the largest concentration of high-tech companies in the United States, at 387,000 high-tech jobs, of which Silicon Valley accounts for 225,300 high-tech jobs. Silicon Valley has the highest concentration of high-tech workers of any metropolitan area, with 285.9 out of every 1,000 private-sector workers. Silicon Valley has the highest average high-tech salary in the United States at $144,800.[70] Largely a result of the high technology sector, the San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, CA Metropolitan Statistical Area has the most millionaires and the most billionaires in the United States per capita.[71]

The region is the biggest high-tech manufacturing center in the United States.[72][73] The unemployment rate of the region was 9.4% in January 2009 and has decreased to a record low of 2.7% as of August 2019.[74] Silicon Valley received 41% of all U.S. venture investment in 2011, and 46% in 2012.[75] More traditional industries also recognize the potential of high-tech development, and several car manufacturers have opened offices in Silicon Valley to capitalize on its entrepreneurial ecosystem.[76]

Manufacture of transistors is, or was, the core industry in Silicon Valley. The production workforce[77] was for the most part composed of Asian and Latino immigrants who were paid low wages and worked in hazardous conditions due to the chemicals used in the manufacture of integrated circuits. Technical, engineering, design, and administrative staffs were in large part[78] well compensated.[79]

Housing[edit]

Silicon Valley has a severe housing shortage, caused by the market imbalance between jobs created and housing units built: from 2010 to 2015, many more jobs have been created than housing units built. (400,000 jobs, 60,000 housing units)[80] This shortage has driven home prices extremely high, far out of the range of production workers.[81] As of 2016 a two-bedroom apartment rented for about $2,500 while the median home price was about $1 million.[80] The Financial Post called Silicon Valley the most expensive U.S. housing region.[82] Homelessness is a problem with housing beyond the reach of middle-income residents; there is little shelter space other than in San Jose which, as of 2015, was making an effort to develop shelters by renovating old hotels.[83]

The Economist also attributes the high cost of living to the success of the industries in this region. Although, this rift between high and low salaries is driving many residents out who can no longer afford to live there. In the Bay Area, the number of residents planning to leave within the next several years has had an increase of 35% since 2016, from 34% to 46%.[84][85]

Notable companies[edit]

Thousands of high technology companies are headquartered in Silicon Valley. Among those, the following are in the Fortune 1000:

- Adobe Inc.

- Advanced Micro Devices

- Agilent Technologies

- Alphabet Inc., includes Google

- Apple Inc.

- Applied Materials

- Block, Inc.

- Broadcom Inc.

- Cadence Design Systems

- Cisco Systems

- eBay

- Electronic Arts

- HP Inc.

- Intel

- Intuit

- Intuitive Surgical

- Juniper Networks

- KLA Corporation

- Lam Research

- Maxim Integrated

- Meta Platforms, includes Facebook

- NetApp

- Netflix

- Nvidia

- PayPal

- Salesforce

- Sanmina Corporation

- Seagate Technology

- ServiceNow

- Synnex

- Synopsys

- Western Digital

Additional notable companies headquartered in Silicon Valley (some of which are defunct, subsumed, or relocated) include:

- 23andMe

- 3Com (acquired by Hewlett-Packard)

- 8×8

- Actel (acquired by Microsemi)

- Actuate Corporation

- Adaptec (acquired by PMC-Sierra)

- Aeria Games and Entertainment

- Altera (acquired by Intel)

- Amazon.com’s A9.com

- Amazon.com’s Lab126.com

- Amdahl (acquired by Fujitsu)

- Atari

- Atmel (acquired by Microchip Technology)

- Brocade Communications Systems (acquired by Broadcom)

- BEA Systems (acquired by Oracle Corporation)

- Cypress Semiconductor (acquired by Infineon Technologies)

- Extreme Networks

- Fairchild Semiconductor (acquired by onsemi)

- Flex (formally Flextronics)

- Foundry Networks (acquired by Brocade Communications Systems)

- Geeknet (Slashdot)

- GlobalFoundries (moved to Malta, New York)

- GoPro

- Harmonic, Inc.

- Hitachi Data Systems

- Hitachi Global Storage Technologies (acquired by Western Digital)

- Hewlett Packard Enterprise (moved to Spring, Texas)

- IDEO

- Informatica

- LinkedIn (acquired by Microsoft)

- Lockheed Martin Space (now headquartered in Denver, Colorado)

- Logitech

- LSI (acquired by Broadcom)

- Maxtor (acquired by Seagate)

- McAfee (acquired by Intel)

- Memorex (acquired by Burroughs)

- Mozilla Foundation

- Move, Inc.

- National Semiconductor (acquired by Texas Instruments)

- Nook (subsidiary of Barnes & Noble)

- Oracle Corporation (moved to Austin, Texas)

- Palm, Inc. (acquired by TCL Corporation)

- PARC

- Proofpoint

- Quantcast

- Quora

- Rambus

- Roku, Inc.

- RSA Security (acquired by EMC)

- SanDisk (acquired by Western Digital)

- SolarCity (acquired by Tesla, Inc.)

- Sony Mobile Communications (U.S. subsidiary headquarters)

- Sony Interactive Entertainment

- SRI International

- Sun Microsystems (acquired by Oracle Corporation)

- SunPower

- SurveyMonkey

- Symantec (now NortonLifeLock and headquartered in Tempe, Arizona)

- Syntex (acquired by Roche)

- Tesla, Inc. (now headquartered in Austin, Texas)

- TIBCO Software

- TiVo (acquired by Xperi)

- Uber

- Verifone (moved to Coral Springs, Florida)

- VeriSign (moved to Reston, Virginia)

- Veritas Technologies (split off from Symantec)

- VMware (acquired by Dell Technologies)

- Walmart Labs

- WebEx (acquired by Cisco Systems)

- YouTube (acquired by Google)

- Yelp, Inc.

- Zoom

- Zynga

- Xilinx (acquired by AMD)

Limits of growth[edit]

The wealth inequality in Silicon Valley is more pronounced than in any other regions of the US. According to 2021 national statistics, 23% of Silicon Valley residents lived below the poverty threshold. In March 2023, the Silicon Valley Bank had triggered a world-wide banking crisis, and an intervention by the U.S. Department of the Treasury. The extreme growth by Silicon Valley companies and the resulting economic crisis had caused the demise of Silicon Valley Bank when the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation stepped in to protect the assets of local residents.[86][87]

Demographics[edit]

Depending on what geographic regions are included in the meaning of the term, the population of Silicon Valley is between 3.5 and 4 million. A 1999 study by AnnaLee Saxenian for the Public Policy Institute of California reported that a third of Silicon Valley scientists and engineers were immigrants and that nearly a quarter of Silicon Valley’s high-technology firms since 1980 were run by Chinese (17 percent) or Indian descent CEOs (7 percent).[88] There is a stratum of well-compensated technical employees and managers, including tens of thousands of «single-digit millionaires». This income and range of assets will support a middle-class lifestyle in Silicon Valley.[89]

Diversity[edit]

Margaret O’Mara, a professor of history at the University of Washington, in 2019 pointed out problematic failures regarding diversity in Silicon Valley. Male oligopolies of high-tech power have recreated traditional environments that repress the talents and ambitions of women, people of color, and other minorities to the benefit of whites and Asian males. [90]

Gender[edit]

In November 2006, the University of California, Davis released a report analyzing business leadership by women within the state.[91] The report showed that although 103 of the 400 largest public companies headquartered in California were located in Santa Clara County (the most of all counties), only 8.8% of Silicon Valley companies had women CEOs.[92]: 4, 7 This was the lowest percentage in the state.[93] (San Francisco County had 19.2% and Marin County had 18.5%.)[92]

Silicon Valley tech leadership positions are occupied almost exclusively by men.[94] This is also represented in the number of new companies founded by women as well as the number of women-lead startups that receive venture capital funding. Wadhwa said he believes that a contributing factor is a lack of parental encouragement to study science and engineering.[95] He also cited a lack of women role models and noted that most famous tech leaders—like Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, and Mark Zuckerberg—are men.[94]

As of October 2014, some high-profile Silicon Valley firms were working actively to prepare and recruit women. Bloomberg reported that Apple, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft attended the 20th annual Grace Hopper Celebration of Women in Computing conference to actively recruit and potentially hire female engineers and technology experts.[96] The same month, the second annual Platform Summit was held to discuss increasing racial and gender diversity in tech.[97] As of April 2015 experienced women were engaged in creation of venture capital firms which leveraged women’s perspectives in funding of startups.[98]

After UC Davis published its Study of California Women Business Leaders in November 2006,[92] some San Jose Mercury News readers dismissed the possibility that sexism contributed in making Silicon Valley’s leadership gender gap the highest in the state. A January 2015 issue of Newsweek magazine featured an article detailing reports of sexism and misogyny in Silicon Valley.[99] The article’s author, Nina Burleigh, asked, «Where were all these offended people when women like Heidi Roizen published accounts of having a venture capitalist stick her hand in his pants under a table while a deal was being discussed?»[100]

Silicon Valley firms’ board of directors are composed of 15.7% women compared with 20.9% in the S&P 100.[101]

The 2012 lawsuit Pao v. Kleiner Perkins was filed in San Francisco County Superior Court by executive Ellen Pao for gender discrimination against her employer, Kleiner Perkins.[102] The case went to trial in February 2015. On March 27, 2015, the jury found in favor of Kleiner Perkins on all counts.[103] Nevertheless, the case, which had wide press coverage, resulted in major advances in consciousness of gender discrimination on the part of venture capital and technology firms and their women employees.[104][105] Two other cases have been filed against Facebook and Twitter.[106]

Statistics[edit]

In 2014, tech companies Google, Yahoo!, Facebook, Apple, and others, released corporate transparency reports that offered detailed employee breakdowns. In May, Google said 17% of its tech employees worldwide were women, and, in the U.S., 1% of its tech workers were black and 2% were Hispanic.[107] June 2014 brought reports from Yahoo! and Facebook. Yahoo! said that 15% of its tech jobs were held by women, 2% of its tech employees were black and 4% Hispanic.[108] Facebook reported that 15% of its tech workforce was female, and 3% was Hispanic and 1% was black.[109] In August, Apple reported that 80% of its global tech staff was male and that, in the U.S., 54% of its tech jobs were staffed by Caucasians and 23% by Asians.[110] Soon after, USA Today published an article about Silicon Valley’s lack of tech-industry diversity, pointing out that it is largely white or Asian, and male. «Blacks and Hispanics are largely absent,» it reported, «and women are underrepresented in Silicon Valley—from giant companies to start-ups to venture capital firms.»[111] Civil rights activist Jesse Jackson said of improving diversity in the tech industry, «This is the next step in the civil rights movement»[112] while T. J. Rodgers has argued against Jackson’s assertions.

According to a 2019 Lincoln Network survey, 48% of high-tech workers in Silicon Valley identify as Christians, with Roman Catholicism (27%) being its largest branch, followed by Protestantism (19%).[113] The same study found that 16% of high-tech workers identify as nothing in particular, 11% as something else, 8% as Agnostics, and 7% as Atheists. Around 4% of high-tech workers in Silicon Valley identify as Jews, 3% as Hindus, and 2% as Muslims.[113]

Municipalities[edit]

The following Santa Clara County cities are traditionally considered to be in Silicon Valley (in alphabetical order):[114][115]

- Campbell

- Cupertino

- Gilroy

- Los Altos

- Los Gatos

- Milpitas

- Morgan Hill

- Mountain View

- Palo Alto

- San Jose

- Santa Clara

- Saratoga

- Sunnyvale

The geographical boundaries of Silicon Valley have changed over the years. Historically, the term Silicon Valley was treated as synonymous with Santa Clara Valley,[1][2][3] and then its meaning later evolved to refer to Santa Clara County plus adjacent regions in southern San Mateo County and southern Alameda County.[116] However, over the years this geographical area has been expanded to include San Francisco County, Contra Costa County, and the northern parts of Alameda County and San Mateo County, this shift has occurred due to the expansion in the local economy and the development of new technologies.[116]

The United States Department of Labor’s Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages program defined Silicon Valley as the counties of Alameda, Contra Costa, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, and Santa Cruz.[117]

In 2015, MIT researchers developed a novel method for measuring which towns are home to startups with higher growth potential and this defines Silicon Valley to center on the municipalities of Menlo Park, Mountain View, Palo Alto, and Sunnyvale.[118][119]

Education[edit]

Funding for public schools in upscale Silicon Valley communities such as Woodside is often supplemented by grants from private foundations set up for that purpose and funded by local residents. Schools in less affluent areas such as East Palo Alto must depend on state funding.[120]

Colleges and universities[edit]

- Bay Area Medical Academy

- California University of Management and Technology

- California South Bay University

- Carnegie Mellon Silicon Valley

- Cañada College

- Chabot College

- De Anza College

- DeVry University

- Evergreen Valley College

- Foothill College

- Gavilan College

- International Technological University

- Lincoln Law School of San Jose

- Menlo College

- Mission College

- National University San Jose Campus

- Northwestern Polytechnic University

- Ohlone College

- Palo Alto University

- Palmer College of Chiropractic, West Campus

- Peralta Colleges

- San Jose City College

- San José State University

- Santa Clara University

- Singularity University

- Sofia University

- Stanford University

- University of California, Santa Cruz, Silicon Valley Campus

- University of San Francisco South Bay Campus

- University of Silicon Valley

- West Valley College

- William Jessup University

Culture[edit]

Events[edit]

- Apple Worldwide Developers Conference, San Jose

- Facebook F8, San Jose

- BayCon, Santa Clara

- Christmas in the Park, San Jose

- Cinequest Film Festival, multiple venues

- FanimeCon, San Jose

- LiveStrong Challenge bike race, San Jose

- Los Altos Art and Wine Festival, Los Altos[121]

- Mountain View Art and Wine Festival, Mountain View[122]

- Palo Alto Festival of the Arts, Palo Alto[123]

- San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival, San Jose

- San Jose Jazz Festival, San Jose

- San Jose Holiday Parade, San Jose

- Silicon Valley Comic Con, San Jose

- Silicon Valley Pride, San Jose

- Stanford Jazz Festival, Stanford

Graphic arts[edit]

- Allied Arts Guild, Menlo Park[124][125]

- Pace Gallery, Palo Alto.[126]

- Pacific Art League

- Movimiento de Arte y Cultura Latino Americana, San Jose

Museums[edit]

- Computer History Museum

- Children’s Discovery Museum of San Jose

- CuriOdyssey

- De Saisset Museum at Santa Clara University

- Hiller Aviation Museum

- History Park by History San José

- The HP Garage

- Intel Museum

- Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University

- Japanese American Museum of San Jose

- Los Altos History Museum

- Moffett Field Historical Society Museum,

- Museum of American Heritage

- Palo Alto Art Center

- Palo Alto Junior Museum and Zoo

- Portuguese Historical Museum

- Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum

- San Mateo County History Museum

- San Jose Museum of Art

- San Jose Museum of Quilts & Textiles

- Sunnyvale Heritage Park Museum

- The Tech Museum of Innovation

- Viet Museum

- Winchester Mystery House

Performing arts[edit]

- American Beethoven Society

- American Musical Theatre of San Jose

- Ballet San Jose

- Bing Concert Hall

- California Youth Symphony

- Opera San José

- Symphony Silicon Valley

- San Jose Center for the Performing Arts

- Broadway San Jose

- San Jose Repertory Theatre

- San Jose Youth Symphony

- San Jose Improv

- SjDANCEco

- Broadway by the Bay

- TheatreWorks Theatre Company

Media[edit]

Headquarters of The Mercury News, Silicon Valley’s largest newspaper, in Downtown San Jose

In 1980, Intelligent Machines Journal changed its name to InfoWorld, and, with offices in Palo Alto, began covering the emergence of the microcomputer industry in the valley.[128]

Local and national media cover Silicon Valley and its companies. CNN, The Wall Street Journal, and Bloomberg News operate Silicon Valley bureaus out of Palo Alto. Public broadcaster KQED (TV) and KQED-FM, as well as the Bay Area’s local ABC station KGO-TV, operate bureaus in San Jose. KNTV, NBC’s local Bay Area affiliate «NBC Bay Area», is located in San Jose. Produced from this location is the nationally distributed TV Show «Tech Now» as well as the CNBC Silicon Valley bureau. San Jose-based media serving Silicon Valley include the San Jose Mercury News daily and the Metro Silicon Valley weekly.

Specialty media include El Observador and the San Jose / Silicon Valley Business Journal. Most of the Bay Area’s other major TV stations, newspapers, and media operate in San Francisco or Oakland. Patch.com operates various web portals, providing local news, discussion and events for residents of Silicon Valley. Mountain View has a public nonprofit station, KMVT-15. KMVT-15’s shows include Silicon Valley Education News (EdNews)-Edward Tico Producer.

Cultural references[edit]

Some appearances in media, in order by release date:

- A View to a Kill—1985 film from the James Bond series. Bond thwarts an elaborate ploy by the film’s antagonist, Max Zorin, to destroy Silicon Valley.[129]

- Triumph of the Nerds: The Rise of Accidental Empires – 1996 documentary

- Pirates of Silicon Valley—1999 film about the early days of Apple Computer and Microsoft (though the latter has never been based in Silicon Valley)

- Code Monkeys—2007 comedy series

- The Social Network—2010 film

- Startups Silicon Valley—reality TV series, debuted 2012 on Bravo[130]

- Betas—TV series, debuted 2013 on Amazon Video[131]

- Jobs—2013 film

- The Internship—2013 comedy film about working at Google

- Silicon Valley—2014 American sitcom from HBO

- Halt and Catch Fire—2014 TV series, the last two seasons are primarily set in Silicon Valley

- Steve Jobs—2015 film

- Watch Dogs 2—2016 video game developed by Ubisoft

- Valley of the Boom—2019 docudrama about the 1990s tech boom in Silicon Valley

- Devs—2020 TV miniseries

- Start-Up—2020 South Korean television series, when three artificial intelligence (A.I.) developers from South Korea are offered positions as engineers for the fictional company, 2STO which is located in Silicon Valley.

- The Dropout—2022 TV miniseries about the rise and fall of Theranos

- Super Pumped—2022 TV series about Travis Kalanick’s time at Uber

See also[edit]

- List of tourist attractions in Silicon Valley

- List of places with «Silicon» names around the world

- List of technology centers around the world

- Semiconductor industry

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Malone, Michael S. (2002). The Valley of Heart’s Delight: A Silicon Valley Notebook 1963 — 2001. New York: John S. Wiley & Sons. p. xix. ISBN 9780471201915. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ^ a b Matthews, Glenna (2003). Silicon Valley, Women, and the California Dream: Gender, Class, and Opportunity in the Twentieth Century. Stanford: Stanford University Press. p. 2. ISBN 9780804741545.

- ^ a b Shueh, Sam (2009). Silicon Valley. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 9780738570938. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ^ Hall, Gina (January 23, 2015). «Silicon Valley Business Journal – San Jose Area has World’s Third-Highest GDP Per Capita, Brookings Says». Archived from the original on March 9, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ^ Kolomatsky, Michael (June 17, 2021). «Where Are the Million-Dollar Homes? — A new report reveals which U.S. metropolitan areas have the highest percentage of homes valued at $1 million or more». The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ «Silicon Valley Index 2022 report» (PDF). Silicon Valley Index. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 4, 2022. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ Carson, Biz. «16 Silicon Valley landmarks you must visit on your next trip». Business Insider. Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- ^ «Tech Headquarters You Can Visit in Silicon Valley». TripSavvy. Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- ^ Sheng, Ellen (December 3, 2018). «Why the headquarters of iconic tech companies are now among America’s top tourist attractions». CNBC. Archived from the original on July 26, 2019. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- ^ a b c Laws, David (January 7, 2015). «Who named Silicon Valley?». Computer History Museum. Archived from the original on October 16, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2018.

- ^ The Frivolous Valley and Its Dreadful Conformity, by Michael Anton (Law & Liberty, published September 4, 2018)

- ^ «Timeline of the history of water in Santa Clara County — Santa Clara Valley Water District». Valleywater.org. Archived from the original on February 8, 2010. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Santa Clara Valley Groundwater Basin, East Bay Plain Subbasin Archived 2020-12-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Valley of Heart’s Delight : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive. Archive.org (2001-03-10). Retrieved on 2013-07-21.

- ^ Golden Harvest…Fifty Years of Calpak Progress : California Packing Corporation, Industrial and Public Relations Department : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive. Archive.org. Retrieved on 2013-07-21.

- ^ https://valleyofheartsdelight.com/Quote:

“The Valley of Heart’s Delight” was the way in which Santa Clara County, home to San Jose and now Silicon Valley, was once described. For those of us who grew up climbing trees in the orchards, and who grow a few fruit trees in their own yards, it still is the Valley of Heart’s Delight. This valley was once famous for wheat, later for grapevines, citrus, nuts, cherry trees, and fruits of all kinds. Hints of the valley’s past are everywhere to be found. - ^ Silicon Valley Turns Fifty, by David Laws, published on January 11, 2021

- ^ Castells, Manuel (2011). The Rise of the Network Society. John Wiley & Sons. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-4443-5631-1. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ^ Sturgeon, Timothy J. (2000). «How Silicon Valley Came to Be». In Kenney, Martin (ed.). Understanding Silicon Valley: The Anatomy of an Entrepreneurial Region. Stanford University. ISBN 978-0-8047-3734-0. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ Black, Dave. «Moffett Field History». moffettfieldmuseum.org. Archived from the original on April 6, 2005. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ Madrigal, Alexis C. (January 15, 2020). «Silicon Valley Abandons the Culture That Made It the Envy of the World». The Atlantic. Archived from the original on January 15, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ a b Markoff, John (April 17, 2009). «Searching for Silicon Valley». The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved April 17, 2009.

- ^ «Scholar examines links between Stanford, Silicon Valley». news.stanford.edu. Retrieved December 11, 2022.

- ^ Stephen B. Adams, «Regionalism in Stanford’s Contribution to the Rise of Silicon Valley», Enterprise & Society 2003 4(3): 521–543

- ^

Frederick Terman — «When Terman returned to Stanford University in 1946 as dean of engineering, he applied his wartime reputation and experience to augmenting the university’s income by encouraging research for the U.S. government […]. - ^ Sandelin, John, The Story of the Stanford Industrial/Research Park, 2004 Archived June 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «History of Computing Industrial Era 1984–1985». thocp.net. Archived from the original on April 28, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^

«The Stanford Research Park: The Engine of Silicon Valley». PaloAltoHistory.com. Archived from the original on March 29, 2014. Retrieved March 29, 2014. - ^ Leonhardt, David (April 6, 2008). «Holding On». The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

In 1955, the physicist William Shockley set up a semiconductor laboratory in Mountain View, partly to be near his mother in Palo Alto. …

- ^ Markoff, John (January 13, 2008). «Two Views of Innovation, Colliding in Washington». The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

The co-inventor of the transistor and the founder of the valley’s first chip company, William Shockley, moved to Palo Alto, Calif., because his mother lived there. …

- ^ Tajnai, Carolyn (May 1985). «Fred Terman, the Father of Silicon Valley». Stanford Computer Forum. Carolyn Terman. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ^ «Silicon Valley’s First Founder Was Its Worst | Backchannel». Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on September 1, 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- ^ Goodheart, Adam (July 2, 2006). «10 Days That Changed History». The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017.

- ^ McLaughlin, John; Weimers, Leigh; Winslow, Ward (2008). Silicon Valley: 110 Year Renaissance. Silicon Valley Historical Association. ISBN 978-0-9649217-4-0. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015.

- ^ Kooi, E.; Schmitz, A. (2005). «Brief Notes on the History of Gate Dielectrics in MOS Devices». High Dielectric Constant Materials: VLSI MOSFET Applications. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 33–44. ISBN 9783540210818.

- ^ a b Black, Lachlan E. (2016). New Perspectives on Surface Passivation: Understanding the Si-Al2O3 Interface. Springer. p. 17. ISBN 9783319325217. Archived from the original on December 30, 2019. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- ^ a b Heywang, W.; Zaininger, K.H. (2013). «2.2. Early history». Silicon: Evolution and Future of a Technology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 26–28. ISBN 9783662098974.

- ^ Lécuyer, Christophe; Brock, David C. (2010). Makers of the Microchip: A Documentary History of Fairchild Semiconductor. MIT Press. p. 111. ISBN 9780262294324. Archived from the original on February 17, 2020. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- ^ a b Feldman, Leonard C. (2001). «Introduction». Fundamental Aspects of Silicon Oxidation. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 1–11. ISBN 9783540416821.

- ^ Sah, Chih-Tang (October 1988). «Evolution of the MOS transistor-from conception to VLSI» (PDF). Proceedings of the IEEE. 76 (10): 1280–1326 (1290). Bibcode:1988IEEEP..76.1280S. doi:10.1109/5.16328. ISSN 0018-9219. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 27, 2019. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

Those of us active in silicon material and device research during 1956–1960 considered this successful effort by the Bell Labs group led by Atalla to stabilize the silicon surface the most important and significant technology advance, which blazed the trail that led to silicon integrated circuit technology developments in the second phase and volume production in the third phase.

- ^ a b c «1960: Metal Oxide Semiconductor (MOS) Transistor Demonstrated». The Silicon Engine. Computer History Museum. Archived from the original on February 20, 2020. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- ^ a b Moskowitz, Sanford L. (2016). Advanced Materials Innovation: Managing Global Technology in the 21st century. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 165–167. ISBN 9780470508923. Archived from the original on December 17, 2019. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ Lojek, Bo (2007). History of Semiconductor Engineering. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 120 & 321–323. ISBN 9783540342588.

- ^ Lécuyer, Christophe (2006). Making Silicon Valley: Innovation and the Growth of High Tech, 1930-1970. Chemical Heritage Foundation. pp. 253–6 & 273. ISBN 9780262122818.

- ^ «1964 – First Commercial MOS IC Introduced». Computer History Museum. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- ^ a b «1971: Microprocessor Integrates CPU Function onto a Single Chip». Computer History Museum. Archived from the original on October 30, 2019. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- ^ Osborne, Adam (1980). An Introduction to Microcomputers. Vol. 1: Basic Concepts (2nd ed.). Berkeley, California: Osborne-McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-931988-34-9. Archived from the original on October 27, 2019. Retrieved August 6, 2019.

- ^ Intel’s First Microprocessor—the Intel 4004, Intel Corp., November 1971, archived from the original on May 13, 2008, retrieved May 17, 2008

- ^ Federico Faggin, The Making of the First Microprocessor Archived October 27, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, IEEE Solid-State Circuits Magazine, Winter 2009, IEEE Xplore

- ^ Intel (April 15, 1974). «From CPU to software, the 8080 Microcomputer is here». Electronic News. New York: Fairchild Publications. pp. 44–45. Electronic News was a weekly trade newspaper. The same advertisement appeared in the May 2, 1974, issue of Electronics magazine.

- ^ Licklider, J. C. R. (April 23, 1963). «Topics for Discussion at the Forthcoming Meeting, Memorandum For: Members and Affiliates of the Intergalactic Computer Network». Washington, D.C.: Advanced Research Projects Agency, via KurzweilAI.net. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- ^ Leiner, Barry M.; et al. (December 10, 2003). ««Origins of the Internet» in A Brief History of the Internet version 3.32″. The Internet Society. Archived from the original on June 4, 2007. Retrieved November 3, 2007.

- ^ Garreau, Joel (2006). Radical Evolution: The Promise and Peril of Enhancing Our Minds, Our Bodies—and what it Means to be Human. Broadway. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-7679-1503-8. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved September 7, 2015.

- ^ a b «Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) (United States Government)». Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on January 11, 2014. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ Christophe Lécuyer, «What Do Universities Really Owe Industry? The Case of Solid State Electronics at Stanford,» Minerva: a Review of Science, Learning & Policy 2005 43(1): 51–71

- ^ Scott, W. Richard; Lara, Bernardo; Biag, Manuelito; Ris, Ethan; Liang, Judy (2017). «The Regional Economy of the San Francisco Bay Area». In Scott, W. Richard; Kirst, Michael W. (eds.). Higher Education and Silicon Valley: Connected But Conflicted. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 65. ISBN 9781421423081. Retrieved August 11, 2019.

- ^ A Legal Bridge Spanning 100 Years: From the Gold Mines of El Dorado to the «Golden» Startups of Silicon Valley Archived June 1, 2013, at the Wayback Machine by Gregory Gromov

- ^ Morris, Rhett (July 26, 2014). «The First Trillion-Dollar Startup». Tech Crunch. Archived from the original on February 22, 2019. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- ^ «Homebrew And How The Apple Came To Be». atariarchives.org. Archived from the original on April 7, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ Markoff, John (2006) [2005]. What the Dormouse Said: How the Sixties Counterculture Shaped the Personal Computer Industry. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-303676-0. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ^ Wozniak, Steve (2006). iWoz. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-393-33043-4.

After my first meeting, I started designing the computer that would later be known as the Apple I. It was that inspiring.

- ^ Freiberger, Paul; Swaine, Michael (2000) [1984]. Fire in the Valley: The Making of the Personal Computer. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-135895-8.

- ^ Graphical User Interface (GUI) Archived October 1, 2002, at the Wayback Machine from apple-history.com

- ^ Waters, John K. (2002). John Chambers and the Cisco Way: Navigating Through Volatility. John Wiley & Sons. p. 28. ISBN 9780471273554.

- ^ W. Josephujjwal sarkar Campbell (January 2, 2015). «The Year of the Internet». 1995: The Year the Future Began. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-27399-3.

- ^ Banks, Marcus (May 16, 2008). «Nonfiction review: ‘Once You’re Lucky’«. San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Reed Albergotti, «The Most Inventive Towns in America», Archived December 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Wall Street Journal, July 22–23, 2006, P1.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ «The Unicorn List». Fortune. January 22, 2015. Archived from the original on April 11, 2015. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- ^ «Cybercities 2008: An Overview of the High-Technology Industry in the Nation’s Top 60 Cities». aeanet.org. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ «America’s Greediest Cities». Forbes. December 3, 2007. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017.

- ^ Albanesius, Chloe (June 24, 2008). «AeA Study Reveals Where the Tech Jobs Are». PC Magazine. Archived from the original on January 12, 2018.

- ^ Pimentel, Benjamin. «Silicon Valley and N.Y. still top tech rankings». MarketWatch. Archived from the original on December 10, 2008. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ «SAN JOSE-SUNNYVALE-SANTA CLARA METROPOLITAN STATISTICAL AREA» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2019.

- ^ «Venture Capital Survey Silicon Valley Fourth Quarter 2011». Fenwick.com. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ «Porsche lands in Silicon Valley to develop sportscars of the future». IBI. May 8, 2017. Archived from the original on May 13, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

Carmakers who have recently expanded to Silicon Valley include Volkswagen, Hyundai, General Motors, Ford, Honda, Toyota, BMW, Nissan and Mercedes-Benz.

- ^ «Production Occupations (Major Group)». bls.gov. Bureau of Labor Statistics. May 2014. Archived from the original on March 20, 2015. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ^ Matthews, Glenda (November 20, 2002). Silicon Valley, Women, and the California Dream: Gender, Class, and Opportunity in the Twentieth Century (1 ed.). Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. pp. 154–56. ISBN 978-0-8047-4796-7. Archived from the original on October 27, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ «Occupational Employment Statistics Semiconductor and Other Electronic Component Manufacturing». bls.gov. Bureau of Labor Statistics. May 2014. Archived from the original on May 5, 2015. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ^ a b Brown, Eliot (June 7, 2016). «Neighbors Clash in Silicon Valley Job growth far outstrips housing, creating an imbalance; San Jose chafes at Santa Clara». The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on June 7, 2016. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ^ Matthews, Glenda (November 20, 2002). Silicon Valley, Women, and the California Dream: Gender, Class, and Opportunity in the Twentieth Century (1 ed.). Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. pp. 233. ISBN 978-0-8047-4796-7. Archived from the original on October 27, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ News, Bloomberg (July 29, 2016). «Zero down on a $2 million house is no problem in Silicon Valley’s ‘weird and scary’ real estate market | Financial Post». Financial Post. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ Potts, Monica (December 13, 2015). «Dispossessed in the Land of Dreams: Those left behind by Silicon Valley’s technology boom struggle to stay in the place they call home». The New Republic. Archived from the original on December 14, 2015. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

A 2013 census showed Santa Clara County having more than 7,000 homeless people, the fifth-highest homeless population per capita in the country and among the highest populations sleeping outside or in unsuitable shelters like vehicles.

- ^ «Silicon Valley is changing, and its lead over other tech hubs narrowing». The Economist. Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- ^ «Why startups are leaving Silicon Valley». The Economist. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

- ^ «Silicon Valley’s Vast Wealth Disparity Continues to Widen as Poverty Increases» kqed.org. Accessed 15 March 2023.

- ^ FDIC Creates a Deposit Insurance National Bank of Santa Clara to Protect Insured Depositors of Silicon Valley Bank, Santa Clara, California fdic.gov. Accessed 15 March 2023.

- ^ Saxenian, AnnaLee (1999). «Silicon Valley’s New Immigrant Entrepreneurs» (PDF). Public Policy Institute of California. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 31, 2016.

- ^ Riflin, Gary (August 5, 2007). «In Silicon Valley, Millionaires Who Don’t Feel Rich». The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 5, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

Silicon Valley is thick with those who might be called working-class millionaires

- ^ Margaret O’Mara. The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America (2019) pp. 2, 7, 320, 398, 401.

- ^ «Women Missing From Decision-Making Roles in State Biz» (Press release). UC Regents. November 16, 2006. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ^ a b c Ellis, Katrina (2006). «UC Davis Study of California Women Business Leaders» (PDF). UC Regents. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ^ Zee, Samantha (November 16, 2006). «California, Silicon Valley Firms Lack Female Leaders (Update1)». Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ^ a b Wadhwa, Vivek (November 9, 2011). «Silicon Valley women are on the rise, but have far to go». Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 25, 2014. Retrieved December 26, 2014.

This is one of Silicon Valley’s most glaring faults: It is male-dominated.

- ^ Wadhwa, Vivek (May 15, 2010). «Fixing Societal Problems: It Starts With Mom and Dad». TechCrunch. AOL. Archived from the original on December 27, 2014. Retrieved December 26, 2014.

- ^ Burrows, Peter (October 8, 2014). «Gender Gap Draws Thousands From Google, Apple to Phoenix». Bloomberg Business. Bloomberg. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2015.