Шаблон:Карточка компании

Intel Corporation (Шаблон:Transcription) — американская корпорация, производящая широкий спектр электронных устройств и компьютерных компонентов, включая микропроцессоры, наборы системной логики (чипсеты) и др. Штаб-квартира — в городе Санта-Клара, штат Калифорния, США.

История[]

Файл:Intelheadquarters.jpg Штаб-квартира в Санта-Клара Энди Гроув, Роберт Нойс и Гордон Мур в 1978

Компанию основали Роберт Нойс и Гордон Мур 18 июля 1968 года[1] после того, как ушли из компании Fairchild Semiconductor. К ним вскоре присоединился Энди Гроув, который разработал и внедрил метод корпоративного управления OKR, эффективно используемый сегодня в менеджменте. Бизнес-план компании был распечатан на печатной машинке Робертом Нойсом и занимал всего одну страницу. Представив его финансисту, который ранее помог создать Fairchild, Intel получила стартовый кредит в $2,5 млн.

Название Integrated Electronics было предложено Гордоном Муром (сначала компанию предполагалось назвать NM Electronics). Нойс одобрил этот вариант, но предложил представить его в сокращенном виде — Intel. Уже после регистрации компании 16 июля 1968 года выяснилось, что существует компания Intelco. Менять название было невыгодно — об Intel уже многие знали, так что во избежание вероятных судебных разбирательств пришлось выплатить $15 000 за право использования выбранного имени.

Шаблон:Sfn

Успех к компании пришёл в 1971, когда Intel начала сотрудничество с японской компанией Busicom. Intel получила заказ на двенадцать специализированных микросхем, но по предложению инженера Тэда Хоффа компания разработала один универсальный микропроцессор Intel 4004. Следующим был разработан Intel 8008.

В 1990-е компания стала крупнейшим производителем процессоров для персональных компьютеров. Серии процессоров Pentium и Celeron до сих порШаблон:Уточнить являются распространёнными.

Intel внесла существенный вклад в развитие компьютерной техники. Спецификации на множество портов, шин, стандартов, систем команд были разработаны при участии компании Intel или же ей самой. Например, такой тип памяти, как DDR, стал известен благодаря ей, хотя долгое время компания продвигала другой тип памяти — RAMBUS RAM (RDRAM).

Собственники и руководство[]

Почти 100 % акций компании находится в свободном обращении на фондовых биржах. Рыночная капитализация на середину июня 2008 года — $128,8 млрд[2].

Председатель совета директоров — Энди Брайант, президент — Рене Джеймс, главный исполнительный директор — Брайан Кржанич.

Руководители[]

- Роберт Нойс — президент компании и главный исполнительный директор в 1968—1975 гг.

- Гордон Мур — президент компании в 1975—1979 гг., главный исполнительный директор в 1975—1987 гг.

- Энди Гроув — президент компании в 1979—1997 гг., главный исполнительный директор в 1987—1998 гг.

- Крэйг Барретт — президент компании в 1997—2002 гг., главный исполнительный директор в 1998—2005 гг.

- Пол Отеллини — президент компании в 2002—2013 гг., главный исполнительный директор в 2005—2013 гг.

- Брайан Кржанич — главный исполнительный директор в 2013—2018 гг.

- Рене Джеймс — президент компании в 2013—2015 гг.

- Эндрю Брайант — председатель совета директоров с 2012 года.

- Роберт Суон — главный исполнительный директор с 30 января 2019 года. Главный финансовый директор в 2016-2018 гг.

Деятельность[]

Intel — крупнейший в мире производитель микропроцессоров, занимающий на 2008 год 75 % этого рынка[2]. Основные покупатели продукции компании (по данным 2013 года) — производители персональных компьютеров Dell (17%), Hewlett-Packard (15%) и Lenovo (12%)[3]. Помимо микропроцессоров, Intel выпускает полупроводниковые компоненты для промышленного и сетевого оборудования.

Показатели деятельности[]

| 2015 год[4] | 2016 год[4] | 2017 год[4] | 2018 год[4] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Выручка от реализации, млрд $ | Шаблон:Падение 55,36 | Шаблон:Рост 59,39 | Шаблон:Рост 62,76 | Шаблон:Рост 70,85 |

| Чистая прибыль, млрд $ | Шаблон:Падение 11,42 | Шаблон:Падение 10,32 | Шаблон:Падение 9,60 | Шаблон:Рост 21,05 |

Intel в России[]

Шаблон:Main

В Российской Федерации у компании имеется три центра НИОКР — в Москве, Новосибирске и Нижнем Новгороде, в последнем работают также специалисты из закрытого в конце 2011 года филиала корпорации в технопарке «Система-Саров» неподалеку от поселка Сатис (Дивеевский район).[5] Помимо исследовательской деятельности, Intel осуществляет в России целый ряд успешных программ в области корпоративной социальной ответственности, особенно в сфере школьного и вузовского образования[6], в частности работает с вузами c целью повысить квалификацию среди студентов и преподавателей по направлениям научных исследований, а также в области технологического предпринимательства. В целом, деятельность корпорации в области образования направлена на повышение уровня институтов, заинтересованных в разработке и продвижении современных образовательных технологий. В Intel активно работает корпоративная программа добровольчества Intel Involved, более 40 процентов штатных сотрудников компании являются добровольцами, помогая местному сообществу.

По программе «Intel® Обучение для будущего» с 2002 года по настоящее время в России более миллиона учителей школ и студентов педагогических ВУЗов прошли обучение тому, как интегрировать элементы ИКТ в учебные планы. Инициатива, объявленная в 2000 году лишь в ряде штатов США, на сегодня охватывает свыше 10 млн учителей более чем из 40 стран мира.

В 2004 году при содействии российского подразделения Intel появилась кафедра микропроцессорных технологий в МФТИ (зав. кафедрой член-корреспондент РАН Б. А. Бабаян, директор по архитектуре подразделения Software and Services Group (SSG) корпорации Intel). Кафедра готовит магистров в области разработки новых вычислительных средств и технологий.

7 апреля 2006 года была открыта учебно-исследовательская лаборатория Intel в Новосибирском государственном университете[7].

В 2011 году компания отпраздновала 20-летие деятельности Intel в РФ и СНГ. В честь этого события в московской школе управления «Сколково» прошла большая партнерская конференция с участием руководства компании[8].

Летом 2015 года компания открыла лабораторию по разработке решений для «интернета вещей» в Москве[9].

Антимонопольные преследования[]

В мае 2009 года Еврокомиссия пришла к заключению, что компания Intel платила скрытые вознаграждения фирмам-производителям компьютеров (таким, как Acer, Dell, HP, Lenovo и NEC), а также продавцам компьютеров, чтобы они отдавали предпочтения процессорам фирмы Intel, а не её конкурента AMD. За нарушение антимонопольного законодательства Intel была оштрафована на рекордную сумму в €1,06 млрд, а также получила строгие предписания «немедленно прекратить незаконную деятельность в случае, если она до сих пор продолжается». Руководство Intel не согласилось с вердиктом Еврокомиссии и подало апелляцию[10].

В начале августа 2009 года Уполномоченный по рассмотрению жалоб (омбудсмен) Евросоюза Никифорос Диамандурос подверг решение Еврокомиссии жёсткой критике. По словам Диамандуроса, Еврокомиссия провела расследование «недобросовестно», упустив хотя бы даже факт своей встречи с представителями второго по величине производителя компьютеров компании Dell, имевшей место в августе 2006 г. Тогда в беседе с комиссарами один из руководителей Dell рассказал, что они используют чипы Intel, так как процессоры AMD «гораздо хуже по качеству». Получается, что Dell сделала выбор в пользу процессоров Intel из технических соображений, а не под влиянием Intel[11]. Так как дело стало публичным, Европейская комиссия решила раскрыть доказательства. Появился пресс-релиз, в котором были представлены фрагменты деловой переписки Intel и вышеназванных компаний. В нём говорилось, что долю AMD на рынке процессоров нужно сократить до 5 и даже 0 %, за что Intel предоставляла этим компаниям различные бонусы.

В итоге в октябре 2009 года большинство разногласий удалось уладить. Intel обязалась выплатить AMD $1,25 млрд, а также следовать определенному набору правил ведения бизнес-деятельности. AMD же обязалась свернуть все судебные дела против Intel по всему миру[12].

16 декабря 2009 года Федеральная торговая комиссия США (FTC) подала иск в суд против Intel. Комиссия обвинила корпорацию в том, что та «путём давления, подкупов и угроз прекращения сотрудничества» принуждала производителей ПК отказываться от сотрудничества с конкурентами. Всё это, по мнению Комиссии, привело к лишению потребителей права выбора, а также к манипулированию ценами и препятствованию инновациям в микроэлектронной промышленности США[13]. Летом 2010 года было достигнуто соглашение с FTC, запрещающее Intel прибегать к ряду методов в своей бизнес-практике. Тем не менее, это соглашение не означает, что в будущем комиссия не подаст против компании другие иски в случае обнаружения новых нарушений.[14][15]

См. также[]

Шаблон:Викиновости-кат

- AMD

- Список микропроцессоров Intel

- OpenCV

- Список чипсетов Intel

- Intel C++ compiler

- Intel Fortran Compiler

- Intel Software Network

- Iometer

- Thunderbolt

- Стратегия «тик-так»

- Закон Мура

Примечания[]

- ↑ Intel Celebrates 40 Years of Innovation

- ↑ 2,0 2,1 Глеб Крампец. «Сила России — в науке и инженерах», — Крейг Баррет, председатель совета директоров Intel // Ведомости, № 111 (2133), 19 июня 2008

- ↑ Шаблон:Cite web

- ↑ 4,0 4,1 4,2 4,3 Ошибка цитирования Неверный тег

<ref>; для сносокFS_2015не указан текст - ↑ Intel открыла Центр исследований и разработок в Новосибирске, Compulenta, 29 октября 2004 года

- ↑ Инициативы Intel® в образовании

- ↑ Состоялась презентация учебно-исследовательской лаборатории НГУ-Intel

- ↑ Будущее согласно Intel // EGZT.ru

- ↑ Шаблон:Cite web

- ↑ Шаблон:Cite news/

- ↑ Шаблон:Cite news/

- ↑ Шаблон:Cite web

- ↑ Власти США начали судебное расследование против Intel

- ↑ Intel и Федеральная торговая комиссия США достигли предварительного согласия

- ↑ Intel пришла к соглашению с Федеральной торговой комиссией

Литература[]

- Шаблон:Книга

- Шаблон:Статья

- Шаблон:Статья

Ссылки[]

- Официальный сайт Intel WorldwideШаблон:Ref-en

- Официальный сайт Intel РоссияШаблон:Ref-ru

- Шаблон:ВТ-ЛП

- Образовательная инициатива Intel

- Инвестфонд «Intel Capital» отчитался о последних инвестициях

- Intel в числе лучших производителей на российском рынке по итогам 2009 года по мнению реселлеров

- История маркетинговой кампании Intel Inside

| Просмотр этого шаблона

Процессоры Intel |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Шаблон:DJIA

Шаблон:Nasdaq 100

Шаблон:Dow Jones Global Titans 50

Шаблон:PHLX Semiconductor Sector

Шаблон:Open Handset Alliance Members

Шаблон:Микроконтроллеры

Шаблон:Нет полных библиографических описаний

Информация о компании Intel Corporation

Компания продает эти платформы в основном OEM-производителям, ODM- производителям и производителям отраслевого и коммуникационного оборудования в комьютерной и коммуникационной отраслях. Платформы Компании используются в широком ряду вычислительных систем, таких как ноутбуки (включая Ultrabook™ устройства и системы 2 в 1-ом), настольные компьютеры, серверы, планшеты, смартфоны, автомобильные информационно-развлекательные системы, автоматизированные производственные линии и медицинское оборудование. Компания также разрабатывает и продает программное обеспечение и услуги, предназначенные в основном для обеспечения безопасности и технологической интеграции.

Первоначально Компания была основана в 1968 году в штате Калифорния, а в 1989 году была зарегистрирована в качестве корпорации в соответствии с законодательством штата Делавэр. Штаб-квартира Intel Corporation находится по адресу: 2200, Мишн Колледж Булевард, Санта Клара, штат Калифорния, 95054-1549, США. Телефонный номер Компании, включая междугородный телефонный код: +1- (408) 765-8080.

Ценные бумаги компании Intel Corporation

Обыкновенные акции Компании прошли листинг на бирже The NASDAQ Stock Market LLC, где они торгуются под символом INTC. По состоянию на 7 февраля 2014 года в реестре акционеров Компании было зарегистрировано около 144 000 акционеров. На вышеуказанную дату было выпущено и находилось в обращении 4 972 000 000 обыкновенных акций. На 20 ноября 2014 года цена закрытия акций составила 35,95 доллара США. Минимальная и максимальная цена акции за 52 недели, предшествующие 20 ноября 2014 года, составляла 23,40 и 35,97 доллара США соответственно.

В2013 и 2012 финансовом году Компания выплатила в качестве дивидендов 4,5 млрд. долларов США (квартальные дивиденды по 0,225 доллара США на обыкновенную акцию) и 4,4 млрд. долларов США (квартальные дивиденды по 0,225 доллара США на обыкновенную акцию в 3 и 4 кварталах и по 0,2100 доллара США на обыкновенную акцию в 1 и 2 кварталах) соответственно и предполагает выплачивать квартальные дивиденды в будущем при условии принятия Советом директоров решения об объявлении дивидендов.

Дополнительная информация о компании Intel Corporation

Отчеты и иная информация, представленная Компанией в SEC, доступны бесплатно на сайте Компании по адресу http://www.intc.com/sec.cfm?DocType=Quarterly по мере публикации таких отчетов на сайте SEC.

Coordinates: 37°23′16″N 121°57′49″W / 37.38778°N 121.96361°W

|

|

Headquarters at Santa Clara in 2017 |

|

|

Trade name |

Intel |

|---|---|

| Formerly | N M Electronics (1968) |

| Type | Public |

|

Traded as |

|

| Industry |

|

| Founded | July 18, 1968; 54 years ago |

| Founders |

|

| Headquarters |

Santa Clara, California , U.S. |

|

Area served |

Worldwide |

|

Key people |

Frank D. Yeary (Chairman) Pat Gelsinger (CEO) |

| Products | Central processing units Microprocessors Integrated graphics processing units (iGPU) Systems-on-chip (SoCs) Motherboard chipsets Network interface controllers Modems Solid state drives Wi-Fi and Bluetooth Chipsets Flash memory Vehicle automation sensors |

| Revenue | |

|

Operating income |

|

|

Net income |

|

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

|

Number of employees |

131,900 (2022) |

| Subsidiaries |

|

| Website | www.intel.com |

| Footnotes / references [1][2] |

Intel Corporation (commonly known as Intel) is an American multinational corporation and technology company headquartered in Santa Clara, California. It is the world’s largest semiconductor chip manufacturer by revenue,[3][4] and is one of the developers of the x86 series of instruction sets found in most personal computers (PCs). Incorporated in Delaware,[5] Intel ranked No. 45 in the 2020 Fortune 500 list of the largest United States corporations by total revenue for nearly a decade, from 2007 to 2016 fiscal years.[6]

Intel supplies microprocessors for computer system manufacturers such as Acer, Lenovo, HP, and Dell. Intel also manufactures motherboard chipsets, network interface controllers and integrated circuits, flash memory, graphics chips, embedded processors and other devices related to communications and computing.

Intel (integrated and electronics) was founded on July 18, 1968, by semiconductor pioneers Gordon Moore (of Moore’s law) and Robert Noyce (1927–1990), and is associated with the executive leadership and vision of Andrew Grove. Intel was a key component of the rise of Silicon Valley as a high-tech center. Noyce was a key inventor of the integrated circuit (microchip).[7][8] Intel was an early developer of SRAM and DRAM memory chips, which represented the majority of its business until 1981. Although Intel created the world’s first commercial microprocessor chip in 1971, it was not until the success of the personal computer (PC) that this became its primary business.

During the 1990s, Intel invested heavily in new microprocessor designs fostering the rapid growth of the computer industry. During this period, Intel became the dominant supplier of microprocessors for PCs and was known for aggressive and anti-competitive tactics in defense of its market position, particularly against AMD, as well as a struggle with Microsoft for control over the direction of the PC industry.[9][10]

The Open Source Technology Center at Intel hosts PowerTOP and LatencyTOP, and supports other open-source projects such as Wayland, Mesa, Threading Building Blocks (TBB), and Xen.[11]

Current operations[edit]

Operating segments[edit]

- Client Computing Group – 51.8% of 2020 revenues – produces PC processors and related components.[12][13]

- Data Center Group – 33.7% of 2020 revenues – produces hardware components used in server, network, and storage platforms.[12]

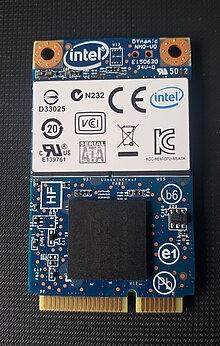

- Non-Volatile Memory Solutions Group – 6.9% of 2020 revenues – produces components for solid-state drives: NAND flash memory and 3D XPoint (Optane).[12]

- Internet of Things Group – 5.2% of 2020 revenues – offers platforms designed for retail, transportation, industrial, buildings and home use.[12]

- Programmable Solutions Group – 2.4% of 2020 revenues – manufactures programmable semiconductors (primarily FPGAs).[12]

Customers[edit]

In 2020, Dell accounted for about 17% of Intel’s total revenues, Lenovo accounted for 12% of total revenues, and HP Inc. accounted for 10% of total revenues.[1] As of August 2021, the US Department of Defense is another large customer for Intel.[14][15][16][17]

[edit]

According to IDC, while Intel enjoyed the biggest market share in both the overall worldwide PC microprocessor market (73.3%) and the mobile PC microprocessor (80.4%) in the second quarter of 2011, the numbers decreased by 1.5% and 1.9% compared to the first quarter of 2011.[18][19]

Intel’s market share decreased significantly in the enthusiast market as of 2019,[20] and they have faced delays for their 10 nm products. According to former Intel CEO Bob Swan, the delay was caused by the company’s overly aggressive strategy for moving to its next node.[21]

[edit]

In the 1980s, Intel was among the top ten sellers of semiconductors (10th in 1987) in the world. It was part of the «Win-Tel» personal computer domination in the 1990s and early 2000s. In 1992, Intel became the biggest chip maker by revenue and held the position until 2018 when it was surpassed by Samsung, but Intel returned to its former position the year after.[22][23] Other major semiconductor companies include TSMC, GlobalFoundries, Samsung, Texas Instruments, Toshiba, STMicroelectronics, United Microelectronics Corporation (UMC), Micron, SK Hynix, Kioxia, and SMIC.

Major competitors[edit]

Intel’s competitors in PC chipsets included AMD, VIA Technologies, Silicon Integrated Systems, and Nvidia. Intel’s competitors in networking include NXP Semiconductors, Infineon,[needs update] Broadcom Limited, Marvell Technology Group and Applied Micro Circuits Corporation, and competitors in flash memory included Spansion, Samsung Electronics, Qimonda, Kioxia, STMicroelectronics, Micron, and SK Hynix.

The only major competitor in the x86 processor market is AMD, with which Intel has had full cross-licensing agreements since 1976: each partner can use the other’s patented technological innovations without charge after a certain time.[24] However, the cross-licensing agreement is canceled in the event of an AMD bankruptcy or takeover.[25]

Some smaller competitors such as VIA Technologies produce low-power x86 processors for small factor computers and portable equipment. However, the advent of such mobile computing devices, in particular, smartphones, has in recent years led to a decline in PC sales.[26] Since over 95% of the world’s smartphones currently use processors cores designed by ARM Holdings, using the ARM instruction set, ARM has become a major competitor for Intel’s processor market. ARM is also planning to make attempts at setting foot into the PC and server market, with Ampere and IBM each individually designing CPUs for servers and supercomputers.[27] The only other major competitor in processor instruction sets is RISC-V, which is an open-source CPU instruction set. With the major phone and telecommunications manufacturer Huawei releasing chips based on the RISC instruction set due to US sanctions.

Intel has been involved in several disputes regarding violation of antitrust laws, which are noted below.

Carbon footprint[edit]

Intel reported Total CO2e emissions (Direct + Indirect) for the twelve months ending 31 December 2020 at 2,882 Kt (+94/+3.4% y-o-y).[28] Intel plans to reduce carbon emissions 10% by 2030 from a 2020 base year.[29]

| Dec 2017 | Dec 2018 | Dec 2019 | Dec 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2,461[30] | 2,578[31] | 2,788[32] | 2,882[28] |

History[edit]

Origins[edit]

Intel was founded in Mountain View, California, on July 18, 1968 by Gordon E. Moore (known for «Moore’s law»), a chemist, and Robert Noyce, a physicist and co-inventor of the integrated circuit. Arthur Rock (investor and venture capitalist) helped them find investors, while Max Palevsky was on the board from an early stage.[33] Moore and Noyce had left Fairchild Semiconductor to found Intel. Rock was not an employee, but he was an investor and was chairman of the board.[34][35] The total initial investment in Intel was $2.5 million in convertible debentures (equivalent to $19.5 million in 2021) and $10,000 from Rock. Just 2 years later, Intel became a public company via an initial public offering (IPO), raising $6.8 million ($23.50 per share).[34] Intel’s third employee was Andy Grove,[note 1] a chemical engineer, who later ran the company through much of the 1980s and the high-growth 1990s.

In deciding on a name, Moore and Noyce quickly rejected «Moore Noyce»,[36] near homophone for «more noise» – an ill-suited name for an electronics company, since noise in electronics is usually undesirable and typically associated with bad interference. Instead, they founded the company as NM Electronics (or MN Electronics) on July 18, 1968, but by the end of the month had changed the name to Intel which stood for Integrated Electronics.[note 2] Since «Intel» was already trademarked by the hotel chain Intelco, they had to buy the rights for the name.[34][42]

Early history[edit]

At its founding, Intel was distinguished by its ability to make logic circuits using semiconductor devices. The founders’ goal was the semiconductor memory market, widely predicted to replace magnetic-core memory. Its first product, a quick entry into the small, high-speed memory market in 1969, was the 3101 Schottky TTL bipolar 64-bit static random-access memory (SRAM), which was nearly twice as fast as earlier Schottky diode implementations by Fairchild and the Electrotechnical Laboratory in Tsukuba, Japan.[43][44] In the same year, Intel also produced the 3301 Schottky bipolar 1024-bit read-only memory (ROM)[45] and the first commercial metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET) silicon gate SRAM chip, the 256-bit 1101.[34][46][47]

While the 1101 was a significant advance, its complex static cell structure made it too slow and costly for mainframe memories. The three-transistor cell implemented in the first commercially available dynamic random-access memory (DRAM), the 1103 released in 1970, solved these issues. The 1103 was the bestselling semiconductor memory chip in the world by 1972, as it replaced core memory in many applications.[48][49] Intel’s business grew during the 1970s as it expanded and improved its manufacturing processes and produced a wider range of products, still dominated by various memory devices.

Intel created the first commercially available microprocessor (Intel 4004) in 1971.[34] The microprocessor represented a notable advance in the technology of integrated circuitry, as it miniaturized the central processing unit of a computer, which then made it possible for small machines to perform calculations that in the past only very large machines could do. Considerable technological innovation was needed before the microprocessor could actually become the basis of what was first known as a «mini computer» and then known as a «personal computer».[50] Intel also created one of the first microcomputers in 1973.[46][51]

Intel opened its first international manufacturing facility in 1972, in Malaysia, which would host multiple Intel operations, before opening assembly facilities and semiconductor plants in Singapore and Jerusalem in the early 1980s, and manufacturing and development centers in China, India, and Costa Rica in the 1990s.[52] By the early 1980s, its business was dominated by dynamic random-access memory (DRAM) chips. However, increased competition from Japanese semiconductor manufacturers had, by 1983, dramatically reduced the profitability of this market. The growing success of the IBM personal computer, based on an Intel microprocessor, was among factors that convinced Gordon Moore (CEO since 1975) to shift the company’s focus to microprocessors and to change fundamental aspects of that business model. Moore’s decision to sole-source Intel’s 386 chip played into the company’s continuing success.

By the end of the 1980s, buoyed by its fortuitous position as microprocessor supplier to IBM and IBM’s competitors within the rapidly growing personal computer market, Intel embarked on a 10-year period of unprecedented growth as the primary (and most profitable) hardware supplier to the PC industry, part of the winning ‘Wintel’ combination. Moore handed over his position as CEO to Andy Grove in 1987. By launching its Intel Inside marketing campaign in 1991, Intel was able to associate brand loyalty with consumer selection, so that by the end of the 1990s, its line of Pentium processors had become a household name.

Challenges to dominance (2000s)[edit]

After 2000, growth in demand for high-end microprocessors slowed. Competitors, most notably AMD (Intel’s largest competitor in its primary x86 architecture market), garnered significant market share, initially in low-end and mid-range processors but ultimately across the product range, and Intel’s dominant position in its core market was greatly reduced,[53] mostly due to controversial NetBurst microarchitecture. In the early 2000s then-CEO, Craig Barrett attempted to diversify the company’s business beyond semiconductors, but few of these activities were ultimately successful.

Litigation[edit]

Intel had also for a number of years been embroiled in litigation. US law did not initially recognize intellectual property rights related to microprocessor topology (circuit layouts), until the Semiconductor Chip Protection Act of 1984, a law sought by Intel and the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA).[54] During the late 1980s and 1990s (after this law was passed), Intel also sued companies that tried to develop competitor chips to the 80386 CPU.[55] The lawsuits were noted to significantly burden the competition with legal bills, even if Intel lost the suits.[55] Antitrust allegations had been simmering since the early 1990s and had been the cause of one lawsuit against Intel in 1991. In 2004 and 2005, AMD brought further claims against Intel related to unfair competition.

Reorganization and success with Intel Core (2005–2015)[edit]

In 2005, CEO Paul Otellini reorganized the company to refocus its core processor and chipset business on platforms (enterprise, digital home, digital health, and mobility).

On June 6, 2005, Steve Jobs, then CEO of Apple, announced that Apple would be using Intel’s x86 processors for its Macintosh computers, switching from the PowerPC architecture developed by the AIM alliance.[56] This was seen as win for Intel,[57] although an analyst called the move «risky» and «foolish», as Intel’s current offerings at the time were considered to be behind those of AMD and IBM.[58]

In 2006, Intel unveiled its Core microarchitecture to widespread critical acclaim; the product range was perceived as an exceptional leap in processor performance that at a stroke regained much of its leadership of the field.[59][60] In 2008, Intel had another «tick» when it introduced the Penryn microarchitecture, fabricated using the 45 nm process node. Later that year, Intel released a processor with the Nehalem architecture to positive reception.[61]

On June 27, 2006, the sale of Intel’s XScale assets was announced. Intel agreed to sell the XScale processor business to Marvell Technology Group for an estimated $600 million and the assumption of unspecified liabilities. The move was intended to permit Intel to focus its resources on its core x86 and server businesses, and the acquisition completed on November 9, 2006.[62]

In 2008, Intel spun off key assets of a solar startup business effort to form an independent company, SpectraWatt Inc. In 2011, SpectraWatt filed for bankruptcy.[63]

In February 2011, Intel began to build a new microprocessor manufacturing facility in Chandler, Arizona, completed in 2013 at a cost of $5 billion.[64] The building is now the 10 nm-certified Fab 42 and is connected to the other Fabs (12, 22, 32) on Ocotillo Campus via an enclosed bridge known as the Link.[65][66][67][68] The company produces three-quarters of its products in the United States, although three-quarters of its revenue come from overseas.[69]

The Alliance for Affordable Internet (A4AI) was launched in October 2013 and Intel is part of the coalition of public and private organizations that also includes Facebook, Google, and Microsoft. Led by Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the A4AI seeks to make Internet access more affordable so that access is broadened in the developing world, where only 31% of people are online. Google will help to decrease Internet access prices so that they fall below the UN Broadband Commission’s worldwide target of 5% of monthly income.[70]

Attempts at entering the smartphone market[edit]

In April 2011, Intel began a pilot project with ZTE Corporation to produce smartphones using the Intel Atom processor for China’s domestic market. In December 2011, Intel announced that it reorganized several of its business units into a new mobile and communications group[71] that would be responsible for the company’s smartphone, tablet, and wireless efforts. Intel planned to introduce Medfield – a processor for tablets and smartphones – to the market in 2012, as an effort to compete with ARM.[72] As a 32-nanometer processor, Medfield is designed to be energy-efficient, which is one of the core features in ARM’s chips.[73]

At the Intel Developers Forum (IDF) 2011 in San Francisco, Intel’s partnership with Google was announced. In January 2012, Google announced Android 2.3, supporting Intel’s Atom microprocessor.[74][75][76] In 2013, Intel’s Kirk Skaugen said that Intel’s exclusive focus on Microsoft platforms was a thing of the past and that they would now support all «tier-one operating systems» such as Linux, Android, iOS, and Chrome.[77]

In 2014, Intel cut thousands of employees in response to «evolving market trends»,[78] and offered to subsidize manufacturers for the extra costs involved in using Intel chips in their tablets. In April 2016, Intel cancelled the SoFIA platform and the Broxton Atom SoC for smartphones,[79][80][81][82] effectively leaving the smartphone market.[83][84]

Intel custom foundry[edit]

Finding itself with excess fab capacity after the failure of the Ultrabook to gain market traction and with PC sales declining, in 2013 Intel reached a foundry agreement to produce chips for Altera using a 14nm process. General Manager of Intel’s custom foundry division Sunit Rikhi indicated that Intel would pursue further such deals in the future.[85] This was after poor sales of Windows 8 hardware caused a major retrenchment for most of the major semiconductor manufacturers, except for Qualcomm, which continued to see healthy purchases from its largest customer, Apple.[86]

As of July 2013, five companies were using Intel’s fabs via the Intel Custom Foundry division: Achronix, Tabula, Netronome, Microsemi, and Panasonic – most are field-programmable gate array (FPGA) makers, but Netronome designs network processors. Only Achronix began shipping chips made by Intel using the 22nm Tri-Gate process.[87][88] Several other customers also exist but were not announced at the time.[89]

The foundry business was closed in 2018 due to Intel’s issues with its manufacturing.[90][91]

Security and manufacturing challenges (2016–2021)[edit]

Intel continued its tick-tock model of a microarchitecture change followed by a die shrink until the 6th generation Core family based on the Skylake microarchitecture. This model was deprecated in 2016, with the release of the seventh generation Core family (codenamed Kaby Lake), ushering in the process–architecture–optimization model. As Intel struggled to shrink their process node from 14 nm to 10 nm, processor development slowed down and the company continued to use the Skylake microarchitecture until 2020, albeit with optimizations.[21]

10 nm process node issues[edit]

While Intel originally planned to introduce 10 nm products in 2016, it later became apparent that there were manufacturing issues with the node.[92] The first microprocessor under that node, Cannon Lake (marketed as 8th generation Core), was released in small quantities in 2018.[93][94] The company first delayed the mass production of their 10 nm products to 2017.[95][96] They later delayed mass production to 2018,[97] and then to 2019. Despite rumors of the process being cancelled,[98] Intel finally introduced mass-produced 10 nm 10th generation Intel Core mobile processors (codenamed «Ice Lake») in September 2019.[99]

Intel later acknowledged that their strategy to shrink to 10 nm was too aggressive.[21][100] While other foundries used up to four steps in 10 nm or 7 nm processes, the company’s 10 nm process required up to five or six multi-pattern steps.[101] In addition, Intel’s 10 nm process is denser than its counterpart processes from other foundries.[102][103] Since Intel’s microarchitecture and process node development were coupled, processor development stagnated.[21]

Security flaws[edit]

In early January 2018, it was reported that all Intel processors made since 1995,[104] excluding Intel Itanium and pre-2013 Intel Atom processors, have been subject to two security flaws dubbed Meltdown and Spectre.[105][106] It is believed that «hundreds of millions» of systems could be affected by these flaws.[107][108] More security flaws were disclosed on May 3, 2018,[109] on August 14, 2018, on January 18, 2019, and on March 5, 2020.[110][111][112][113]

On March 15, 2018, Intel reported that it will redesign its CPUs to protect against the Spectre security vulnerability, the redesigned processors were sold later in 2018.[114][115] Existing chips vulnerable to Meltdown and Spectre can be fixed with a software patch at a cost to performance.[116][117][118][119]

Renewed competition and other developments (2018–present)[edit]

Due to Intel’s issues with its 10 nm process node and the company’s slow processor development,[21] the company now found itself in a market with intense competition.[120] The company’s main competitor, AMD, introduced the Zen microarchitecture and a new chiplet based design to critical acclaim. Since its introduction, AMD, once unable to compete with Intel in the high-end CPU market, has undergone a resurgence,[121] and Intel’s dominance and market share have considerably decreased.[122] In addition, Apple is switching from the x86 architecture and Intel processors to their own Apple silicon for their Macintosh computers from 2020 onwards. The transition is expected to affect Intel minimally; however, it might prompt other PC manufacturers to reevaluate their reliance on Intel and the x86 architecture.[123][124]

‘IDM 2.0’ strategy[edit]

On March 23, 2021, CEO Pat Gelsinger laid out new plans for the company.[125] These include a new strategy, called IDM 2.0, that includes investments in manufacturing facilities, use of both internal and external foundries, and a new foundry business called Intel Foundry Services (IFS), a standalone business unit.[126][127] Unlike Intel Custom Foundry, IFS will offer a combination of packaging and process technology, and Intel’s IP portfolio including x86 cores. Other plans for the company include a partnership with IBM and a new event for developers and engineers, called «Intel ON».[91] Gelsinger also confirmed that Intel’s 7 nm process is on track, and that the first products using their 7 nm process (also known as Intel 4) are Ponte Vecchio and Meteor Lake.[91]

In January 2022, Intel reportedly selected New Albany, Ohio, near Columbus, Ohio, as the site for a major new manufacturing facility.[128] The facility will cost at least $20 billion.[129] The company expects the facility to begin producing chips by 2025.[130] The same year Intel also choose Magdeburg, Germany, as a site for two new chip mega factories for €17 billion (topping Tesla’s investment in Brandenburg). Groundbreaking is planned for 2023, while production start is planned for 2027. Including subcontractors this would create 10.000 new jobs.[131]

In August 2022, Intel signed a $30 billion partnership with Brookfield Asset Management to fund its recent factory expansions. As part of the deal, Intel would have a controlling stake by funding 51% of the cost of building new chip-making facilities in Chandler, with Brookfield owning the remaining 49% stake, allowing the companies to split the revenue from those facilities.[132][133]

On January 31, 2023, as part of $3 billion in cost reductions, Intel announced pay cuts affecting employees above midlevel, ranging from 5% upwards. It also suspended bonuses and merit pay increases, while reducing retirement plan matching. These cost reductions followed layoffs announced in the fall of 2022. [134]

Product and market history[edit]

SRAMs, DRAMs, and the microprocessor[edit]

Intel’s first products were shift register memory and random-access memory integrated circuits, and Intel grew to be a leader in the fiercely competitive DRAM, SRAM, and ROM markets throughout the 1970s. Concurrently, Intel engineers Marcian Hoff, Federico Faggin, Stanley Mazor, and Masatoshi Shima invented Intel’s first microprocessor. Originally developed for the Japanese company Busicom to replace a number of ASICs in a calculator already produced by Busicom, the Intel 4004 was introduced to the mass market on November 15, 1971, though the microprocessor did not become the core of Intel’s business until the mid-1980s. (Note: Intel is usually given credit with Texas Instruments for the almost-simultaneous invention of the microprocessor)

In 1983, at the dawn of the personal computer era, Intel’s profits came under increased pressure from Japanese memory-chip manufacturers, and then-president Andy Grove focused the company on microprocessors. Grove described this transition in the book Only the Paranoid Survive. A key element of his plan was the notion, then considered radical, of becoming the single source for successors to the popular 8086 microprocessor.

Until then, the manufacture of complex integrated circuits was not reliable enough for customers to depend on a single supplier, but Grove began producing processors in three geographically distinct factories,[which?] and ceased licensing the chip designs to competitors such as AMD.[135] When the PC industry boomed in the late 1980s and 1990s, Intel was one of the primary beneficiaries.

Early x86 processors and the IBM PC[edit]

The die from an Intel 8742, an 8-bit microcontroller that includes a CPU running at 12 MHz, 128 bytes of RAM, 2048 bytes of EPROM, and I/O in the same chip

Despite the ultimate importance of the microprocessor, the 4004 and its successors the 8008 and the 8080 were never major revenue contributors at Intel. As the next processor, the 8086 (and its variant the 8088) was completed in 1978, Intel embarked on a major marketing and sales campaign for that chip nicknamed «Operation Crush», and intended to win as many customers for the processor as possible. One design win was the newly created IBM PC division, though the importance of this was not fully realized at the time.

IBM introduced its personal computer in 1981, and it was rapidly successful. In 1982, Intel created the 80286 microprocessor, which, two years later, was used in the IBM PC/AT. Compaq, the first IBM PC «clone» manufacturer, produced a desktop system based on the faster 80286 processor in 1985 and in 1986 quickly followed with the first 80386-based system, beating IBM and establishing a competitive market for PC-compatible systems and setting up Intel as a key component supplier.

In 1975, the company had started a project to develop a highly advanced 32-bit microprocessor, finally released in 1981 as the Intel iAPX 432. The project was too ambitious and the processor was never able to meet its performance objectives, and it failed in the marketplace. Intel extended the x86 architecture to 32 bits instead.[136][137]

386 microprocessor[edit]

During this period Andrew Grove dramatically redirected the company, closing much of its DRAM business and directing resources to the microprocessor business. Of perhaps greater importance was his decision to «single-source» the 386 microprocessor. Prior to this, microprocessor manufacturing was in its infancy, and manufacturing problems frequently reduced or stopped production, interrupting supplies to customers. To mitigate this risk, these customers typically insisted that multiple manufacturers produce chips they could use to ensure a consistent supply. The 8080 and 8086-series microprocessors were produced by several companies, notably AMD, with which Intel had a technology-sharing contract.

Grove made the decision not to license the 386 design to other manufacturers, instead, producing it in three geographically distinct factories: Santa Clara, California; Hillsboro, Oregon; and Chandler, a suburb of Phoenix, Arizona. He convinced customers that this would ensure consistent delivery. In doing this, Intel breached its contract with AMD, which sued and was paid millions of dollars in damages but could not manufacture new Intel CPU designs any longer. (Instead, AMD started to develop and manufacture its own competing x86 designs.)

As the success of Compaq’s Deskpro 386 established the 386 as the dominant CPU choice, Intel achieved a position of near-exclusive dominance as its supplier. Profits from this funded rapid development of both higher-performance chip designs and higher-performance manufacturing capabilities, propelling Intel to a position of unquestioned leadership by the early 1990s.

486, Pentium, and Itanium[edit]

Intel introduced the 486 microprocessor in 1989, and in 1990 established a second design team, designing the processors code-named «P5» and «P6» in parallel and committing to a major new processor every two years, versus the four or more years such designs had previously taken. Engineers Vinod Dham and Rajeev Chandrasekhar (Member of Parliament, India) were key figures on the core team that invented the 486 chip and later, Intel’s signature Pentium chip. The P5 project was earlier known as «Operation Bicycle», referring to the cycles of the processor through two parallel execution pipelines. The P5 was introduced in 1993 as the Intel Pentium, substituting a registered trademark name for the former part number (numbers, such as 486, cannot be legally registered as trademarks in the United States). The P6 followed in 1995 as the Pentium Pro and improved into the Pentium II in 1997. New architectures were developed alternately in Santa Clara, California and Hillsboro, Oregon.

The Santa Clara design team embarked in 1993 on a successor to the x86 architecture, codenamed «P7». The first attempt was dropped a year later but quickly revived in a cooperative program with Hewlett-Packard engineers, though Intel soon took over primary design responsibility. The resulting implementation of the IA-64 64-bit architecture was the Itanium, finally introduced in June 2001. The Itanium’s performance running legacy x86 code did not meet expectations, and it failed to compete effectively with x86-64, which was AMD’s 64-bit extension of the 32-bit x86 architecture (Intel uses the name Intel 64, previously EM64T). In 2017, Intel announced that the Itanium 9700 series (Kittson) would be the last Itanium chips produced.[138][139]

The Hillsboro team designed the Willamette processors (initially code-named P68), which were marketed as the Pentium 4.

During this period, Intel undertook two major supporting advertising campaigns. The first campaign, the 1991 «Intel Inside» marketing and branding campaign, is widely known and has become synonymous with Intel itself. The idea of «ingredient branding» was new at the time, with only NutraSweet and a few others making attempts to do so.[140] This campaign established Intel, which had been a component supplier little-known outside the PC industry, as a household name.

The second campaign, Intel’s Systems Group, which began in the early 1990s, showcased manufacturing of PC motherboards, the main board component of a personal computer, and the one into which the processor (CPU) and memory (RAM) chips are plugged.[141] The Systems Group campaign was lesser known than the Intel Inside campaign.

Shortly after, Intel began manufacturing fully configured «white box» systems for the dozens of PC clone companies that rapidly sprang up.[citation needed] At its peak in the mid-1990s, Intel manufactured over 15% of all PCs, making it the third-largest supplier at the time.[citation needed]

During the 1990s, Intel Architecture Labs (IAL) was responsible for many of the hardware innovations for the PC, including the PCI Bus, the PCI Express (PCIe) bus, and Universal Serial Bus (USB). IAL’s software efforts met with a more mixed fate; its video and graphics software was important in the development of software digital video,[citation needed] but later its efforts were largely overshadowed by competition from Microsoft. The competition between Intel and Microsoft was revealed in testimony by then IAL Vice-president Steven McGeady at the Microsoft antitrust trial (United States v. Microsoft Corp.).

Pentium flaw[edit]

In June 1994, Intel engineers discovered a flaw in the floating-point math subsection of the P5 Pentium microprocessor. Under certain data-dependent conditions, the low-order bits of the result of a floating-point division would be incorrect. The error could compound in subsequent calculations. Intel corrected the error in a future chip revision, and under public pressure it issued a total recall and replaced the defective Pentium CPUs (which were limited to some 60, 66, 75, 90, and 100 MHz models[142]) on customer request.

The bug was discovered independently in October 1994 by Thomas Nicely, Professor of Mathematics at Lynchburg College. He contacted Intel but received no response. On October 30, he posted a message about his finding on the Internet.[143] Word of the bug spread quickly and reached the industry press. The bug was easy to replicate; a user could enter specific numbers into the calculator on the operating system. Consequently, many users did not accept Intel’s statements that the error was minor and «not even an erratum». During Thanksgiving, in 1994, The New York Times ran a piece by journalist John Markoff spotlighting the error. Intel changed its position and offered to replace every chip, quickly putting in place a large end-user support organization. This resulted in a $475 million charge against Intel’s 1994 revenue.[144] Dr. Nicely later learned that Intel had discovered the FDIV bug in its own testing a few months before him (but had decided not to inform customers).[145]

The «Pentium flaw» incident, Intel’s response to it, and the surrounding media coverage propelled Intel from being a technology supplier generally unknown to most computer users to a household name. Dovetailing with an uptick in the «Intel Inside» campaign, the episode is considered to have been a positive event for Intel, changing some of its business practices to be more end-user focused and generating substantial public awareness, while avoiding a lasting negative impression.[146]

Intel Core[edit]

The Intel Core line originated from the original Core brand, with the release of the 32-bit Yonah CPU, Intel’s first dual-core mobile (low-power) processor. Derived from the Pentium M, the processor family used an enhanced version of the P6 microarchitecture. Its successor, the Core 2 family, was released on July 27, 2006. This was based on the Intel Core microarchitecture, and was a 64-bit design.[147] Instead of focusing on higher clock rates, the Core microarchitecture emphasized power efficiency and a return to lower clock speeds.[148] It also provided more efficient decoding stages, execution units, caches, and buses, reducing the power consumption of Core 2-branded CPUs while increasing their processing capacity.

In November 2008, Intel released the first generation Core processors based on the Nehalem microarchitecture. Intel also introduced a new naming scheme, with the three variants now named Core i3, i5, and i7 (as well as i9 from 7th generation onwards). Unlike the previous naming scheme, these names no longer correspond to specific technical features. It was succeeded by the Westmere microarchitecture in 2010, with a die shrink to 32 nm and included Intel HD Graphics.

In 2011, Intel released the Sandy Bridge-based 2nd generation Core processor family. This generation featured an 11% performance increase over Nehalem.[149] It was succeeded by Ivy Bridge-based 3rd generation Core, introduced at the 2012 Intel Developer Forum.[150] Ivy Bridge featured a die shrink to 22 nm, and supported both DDR3 memory and DDR3L chips.

Intel continued its tick-tock model of a microarchitecture change followed by a die shrink until the 6th generation Core family based on the Skylake microarchitecture. This model was deprecated in 2016, with the release of the seventh generation Core family based on Kaby Lake, ushering in the process–architecture–optimization model.[151] From 2016 until 2021, Intel later released more optimizations on the Skylake microarchitecture with Kaby Lake R, Amber Lake, Whiskey Lake, Coffee Lake, Coffee Lake R, and Comet Lake.[152][153][154][155] Intel struggled to shrink their process node from 14 nm to 10 nm, with the first microarchitecture under that node, Cannon Lake (marketed as 8th generation Core), only being released in small quantities in 2018.[93][94]

In 2019, Intel released the 10th generation of Core processors, codenamed «Amber Lake», «Comet Lake», and «Ice Lake». Ice Lake, based on the Sunny Cove microarchitecture, was produced on the 10 nm process and was limited to low-power mobile processors. Both Amber Lake and Comet Lake were based on a refined 14 nm node, with the latter being used for desktop and high performance mobile products and the former used for low-power mobile products.

In September 2020, 11th generation Core mobile processors, codenamed Tiger Lake, were launched.[156] Tiger Lake is based on the Willow Cove microarchitecture and a refined 10 nm node.[157] Intel later released 11th generation Core desktop processors (codenamed «Rocket Lake»), fabricated using Intel’s 14 nm process and based on the Cypress Cove microarchitecture,[158] on March 30, 2021.[159] It replaced Comet Lake desktop processors. All 11th generation Core processors feature new integrated graphics based on the Intel Xe microarchitecture.[160]

Both desktop and mobile products were unified under a single process node with the release of 12th generation Intel Core processors (codenamed «Alder Lake») in late 2021.[161][162] This generation will be fabricated using Intel’s 7 nm process, called Intel 7, for both desktop and mobile processors, and is based on a hybrid architecture utilizing high-performance Golden Cove cores and high-efficiency Gracemont (Atom) cores.[161]

Meltdown, Spectre, and other security vulnerabilities[edit]

In early January 2018, it was reported that all Intel processors made since 1995[163][107] (besides Intel Itanium and pre-2013 Intel Atom) have been subject to two security flaws dubbed Meltdown and Spectre.[164][106]

The impact on performance resulting from software patches is «workload-dependent». Several procedures to help protect home computers and related devices from the Spectre and Meltdown security vulnerabilities have been published.[165][166][167][168] Spectre patches have been reported to significantly slow down performance, especially on older computers; on the newer 8th generation Core platforms, benchmark performance drops of 2–14 percent have been measured.[116] Meltdown patches may also produce performance loss.[117][118][119] It is believed that «hundreds of millions» of systems could be affected by these flaws.[107][169]

On March 15, 2018, Intel reported that it will redesign its CPUs (performance losses to be determined) to protect against the Spectre security vulnerability, and expects to release the newly redesigned processors later in 2018.[114][115]

On May 3, 2018, eight additional Spectre-class flaws were reported. Intel reported that they are preparing new patches to mitigate these flaws.[170]

On August 14, 2018, Intel disclosed three additional chip flaws referred to as L1 Terminal Fault (L1TF). They reported that previously released microcode updates, along with new, pre-release microcode updates can be used to mitigate these flaws.[171][172]

On January 18, 2019, Intel disclosed three new vulnerabilities affecting all Intel CPUs, named «Fallout», «RIDL», and «ZombieLoad», allowing a program to read information recently written, read data in the line-fill buffers and load ports, and leak information from other processes and virtual machines.[173][174][175] Coffeelake-series CPUs are even more vulnerable, due to hardware mitigations for Spectre.[citation needed]

On March 5, 2020, computer security experts reported another Intel chip security flaw, besides the Meltdown and Spectre flaws, with the systematic name CVE-2019-0090 (or, «Intel CSME Bug»).[110] This newly found flaw is not fixable with a firmware update, and affects nearly «all Intel chips released in the past five years».[111][112][113]

Use of Intel products by Apple Inc. (2005–2019)[edit]

On June 6, 2005, Steve Jobs, then CEO of Apple, announced that Apple would be transitioning the Macintosh from its long favored PowerPC architecture to the Intel x86 architecture because the future PowerPC road map was unable to satisfy Apple’s needs.[56][176] This was seen as a win for Intel,[57] although an analyst called the move «risky» and «foolish», as Intel’s current offerings at the time were considered to be behind those of AMD and IBM.[58] The first Mac computers containing Intel CPUs were announced on January 10, 2006, and Apple had its entire line of consumer Macs running on Intel processors by early August 2006. The Apple Xserve server was updated to Intel Xeon processors from November 2006 and was offered in a configuration similar to Apple’s Mac Pro.[177]

Despite Apple’s use of Intel products, relations between the two companies were strained at times.[178] Rumors of Apple switching from Intel processors to their own designs began circulating as early as 2011.[179] On June 22, 2020, during Apple’s annual WWDC, Tim Cook, Apple’s CEO, announced that they would be transitioning their entire Mac line from Intel CPUs to custom Apple-designed processors over the course of the next two years. In the short term, this transition is estimated to have minimal effects on Intel, as Apple only accounts for 2% to 4% of their revenue. However, Apple’s shift to their own chips might prompt other PC manufacturers to reassess their reliance on Intel and the x86 architecture.[123][124] By November 2020, Apple unveiled the M1, their processor designed for the Mac.[180][181][182][183]

Solid-state drives (SSD)[edit]

In 2008, Intel began shipping mainstream solid-state drives (SSDs) with up to 160 GB storage capacities.[184] As with their CPUs, Intel develops SSD chips using ever-smaller nanometer processes. These SSDs make use of industry standards such as NAND flash,[185] mSATA,[186] PCIe, and NVMe. In 2017, Intel introduced SSDs based on 3D XPoint technology under the Optane brand name.[187]

In 2021, SK Hynix acquired most of Intel’s NAND memory business[188] for $7 billion, with a remaining transaction worth $2 billion expected in 2025.[189] Intel also discontinued its consumer Optane products in 2021.[190] In July 2022, Intel disclosed in its Q2 earnings report that it would cease future product development within its Optane business.[191]

Supercomputers[edit]

The Intel Scientific Computers division was founded in 1984 by Justin Rattner, to design and produce parallel computers based on Intel microprocessors connected in hypercube internetwork topology.[192] In 1992, the name was changed to the Intel Supercomputing Systems Division, and development of the iWarp architecture was also subsumed.[193] The division designed several supercomputer systems, including the Intel iPSC/1, iPSC/2, iPSC/860, Paragon and ASCI Red. In November 2014, Intel stated that it was planning to use optical fibers to improve networking within supercomputers.[194]

Fog computing[edit]

On November 19, 2015, Intel, alongside ARM Holdings, Dell, Cisco Systems, Microsoft, and Princeton University, founded the OpenFog Consortium, to promote interests and development in fog computing.[195] Intel’s Chief Strategist for the IoT Strategy and Technology Office, Jeff Fedders, became the consortium’s first president.[196]

Self-driving cars[edit]

Intel is one of the biggest stakeholders in the self-driving car industry, having joined the race in mid 2017[197] after joining forces with Mobileye.[198] The company is also one of the first in the sector to research consumer acceptance, after an AAA report quoted a 78% nonacceptance rate of the technology in the US.[199]

Safety levels of the technology, the thought of abandoning control to a machine, and psychological comfort of passengers in such situations were the major discussion topics initially. The commuters also stated that they did not want to see everything the car was doing. This was primarily a referral to the auto-steering wheel with no one sitting in the driving seat. Intel also learned that voice control regulator is vital, and the interface between the humans and machine eases the discomfort condition, and brings some sense of control back.[200] It is important to mention that Intel included only 10 people in this study, which makes the study less credible.[199] In a video posted on YouTube,[201] Intel accepted this fact and called for further testing.

Programmable devices[edit]

Intel has sold Stratix, Arria, and Cyclone FPGAs since acquiring Altera in 2015. In 2019, Intel released Agilex FPGAs: chips aimed at data centers, 5G applications, and other uses.[202]

Competition, antitrust and espionage[edit]

By the end of the 1990s, microprocessor performance had outstripped software demand for that CPU power. Aside from high-end server systems and software, whose demand dropped with the end of the «dot-com bubble», consumer systems ran effectively on increasingly low-cost systems after 2000. Intel’s strategy of producing ever-more-powerful processors and obsoleting their predecessors stumbled,[citation needed] leaving an opportunity for rapid gains by competitors, notably AMD. This, in turn, lowered the profitability[citation needed] of the processor line and ended an era of unprecedented dominance of the PC hardware by Intel.[citation needed]

Intel’s dominance in the x86 microprocessor market led to numerous charges of antitrust violations over the years, including FTC investigations in both the late 1980s and in 1999, and civil actions such as the 1997 suit by Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) and a patent suit by Intergraph. Intel’s market dominance (at one time[when?] it controlled over 85% of the market for 32-bit x86 microprocessors) combined with Intel’s own hardball legal tactics (such as its infamous 338 patent suit versus PC manufacturers)[203] made it an attractive target for litigation, culminating in Intel agreeing to pay AMD $1.25B and grant them a perpetual patent cross-license in 2009 as well as several anti-trust judgements in Europe, Korea, and Japan.[204]

A case of industrial espionage arose in 1995 that involved both Intel and AMD. Bill Gaede, an Argentine formerly employed both at AMD and at Intel’s Arizona plant, was arrested for attempting in 1993 to sell the i486 and P5 Pentium designs to AMD and to certain foreign powers.[205] Gaede videotaped data from his computer screen at Intel and mailed it to AMD, which immediately alerted Intel and authorities, resulting in Gaede’s arrest. Gaede was convicted and sentenced to 33 months in prison in June 1996.[206][207]

Corporate affairs[edit]

Leadership and corporate structure[edit]

Paul Otellini, Craig Barrett and Sean Maloney in 2006

Robert Noyce was Intel’s CEO at its founding in 1968, followed by co-founder Gordon Moore in 1975. Andy Grove became the company’s president in 1979 and added the CEO title in 1987 when Moore became chairman. In 1998, Grove succeeded Moore as chairman, and Craig Barrett, already company president, took over. On May 18, 2005, Barrett handed the reins of the company over to Paul Otellini, who had been the company president and COO and who was responsible for Intel’s design win in the original IBM PC. The board of directors elected Otellini as president and CEO, and Barrett replaced Grove as Chairman of the Board. Grove stepped down as chairman but is retained as a special adviser. In May 2009, Barrett stepped down as chairman of the board and was succeeded by Jane Shaw. In May 2012, Intel vice chairman Andy Bryant, who had held the posts of CFO (1994) and Chief Administrative Officer (2007) at Intel, succeeded Shaw as executive chairman.[208]

In November 2012, president and CEO Paul Otellini announced that he would step down in May 2013 at the age of 62, three years before the company’s mandatory retirement age. During a six-month transition period, Intel’s board of directors commenced a search process for the next CEO, in which it considered both internal managers and external candidates such as Sanjay Jha and Patrick Gelsinger.[209] Financial results revealed that, under Otellini, Intel’s revenue increased by 55.8 percent (US$34.2 to 53.3 billion), while its net income increased by 46.7% (US$7.5 billion to 11 billion),[210] proving that his illegal business practices were more profitable than the fines levied against the company as punishment for employing them.

On May 2, 2013, Executive Vice President and COO Brian Krzanich was elected as Intel’s sixth CEO,[211] a selection that became effective on May 16, 2013, at the company’s annual meeting. Reportedly, the board concluded that an insider could proceed with the role and exert an impact more quickly, without the need to learn Intel’s processes, and Krzanich was selected on such a basis.[212] Intel’s software head Renée James was selected as president of the company, a role that is second to the CEO position.[213]

As of May 2013, Intel’s board of directors consists of Andy Bryant, John Donahoe, Frank Yeary, Ambassador Charlene Barshefsky, Susan Decker, Reed Hundt, Paul Otellini, James Plummer, David Pottruck, and David Yoffie and Creative director will.i.am. The board was described by former Financial Times journalist Tom Foremski as «an exemplary example of corporate governance of the highest order» and received a rating of ten from GovernanceMetrics International, a form of recognition that has only been awarded to twenty-one other corporate boards worldwide.[214]

On June 21, 2018, Intel announced the resignation of Brian Krzanich as CEO, with the exposure of a relationship he had with an employee. Bob Swan was named interim CEO, as the Board began a search for a permanent CEO.

On January 31, 2019, Swan transitioned from his role as CFO and interim CEO and was named by the Board as the seventh CEO to lead the company.[215]

On January 13, 2021, Intel announced that Swan would be replaced as CEO by Pat Gelsinger, effective February 15. Gelsinger is a former Intel chief technology officer who had previously been head of VMWare.[216]

Board of directors[edit]

As of March 2023:[217]

- Frank D. Yeary (chairman), managing member of Darwin Capital

- Pat Gelsinger, CEO of Intel[218]

- James Goetz, managing director of Sequoia Capital

- Andrea Goldsmith, dean of engineering and applied science at Princeton University

- Alyssa Henry, Square, Inc. executive

- Omar Ishrak, chairman and former CEO of Medtronic

- Risa Lavizzo-Mourey, former president and CEO of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

- Tsu-Jae King Liu, professor at the UC Berkeley College of Engineering

- Barbara G. Novick, co-founder of BlackRock

- Gregory Smith, CFO of Boeing

- Dion Weisler, former president and CEO of HP Inc.

- Lip-Bu Tan, executive chairman of Cadence Design Systems

Employment[edit]

Intel microprocessor facility in Costa Rica was responsible in 2006 for 20% of Costa Rican exports and 4.9% of the country’s GDP.[219]

Intel has a mandatory retirement policy for its CEOs when they reach age 65. Andy Grove retired at 62, while both Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore retired at 58. Grove retired as chairman and as a member of the board of directors in 2005 at age 68.

Intel’s headquarters are located in Santa Clara, California, and the company has operations around the world. Its largest workforce concentration anywhere is in Washington County, Oregon[220] (in the Portland metropolitan area’s «Silicon Forest»), with 18,600 employees at several facilities.[221] Outside the United States, the company has facilities in China, Costa Rica, Malaysia, Israel, Ireland, India, Russia, Argentina and Vietnam, in 63 countries and regions internationally. In March 2022, because of International sanctions during the Russo-Ukrainian War, Intel stopped supplying Russian market.[222] In the U.S. Intel employs significant numbers of people in California, Colorado, Massachusetts, Arizona, New Mexico, Oregon, Texas, Washington and Utah. In Oregon, Intel is the state’s largest private employer.[221][223] The company is the largest industrial employer in New Mexico while in Arizona the company has 12,000 employees as of January 2020.[224]

Intel invests heavily in research in China and about 100 researchers – or 10% of the total number of researchers from Intel – are located in Beijing.[225]

In 2011, the Israeli government offered Intel $290 million to expand in the country. As a condition, Intel would employ 1,500 more workers in Kiryat Gat and between 600 and 1000 workers in the north.[226]

In January 2014, it was reported that Intel would cut about 5,000 jobs from its work force of 107,000. The announcement was made a day after it reported earnings that missed analyst targets.[227]

In March 2014, it was reported that Intel would embark upon a $6 billion plan to expand its activities in Israel. The plan calls for continued investment in existing and new Intel plants until 2030. As of 2014, Intel employs 10,000 workers at four development centers and two production plants in Israel.[228]

Due to declining PC sales, in 2016 Intel cut 12,000 jobs.[229] In 2021, Intel reversed course under new CEO Pat Gelsinger and started hiring thousands of engineers.[230]

Diversity[edit]

Intel has a Diversity Initiative, including employee diversity groups as well as supplier diversity programs.[231] Like many companies with employee diversity groups, they include groups based on race and nationality as well as sexual identity and religion. In 1994, Intel sanctioned one of the earliest corporate Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender employee groups,[232] and supports a Muslim employees group,[233] a Jewish employees group,[234] and a Bible-based Christian group.[235][236]

Intel has received a 100% rating on numerous Corporate Equality Indices released by the Human Rights Campaign including the first one released in 2002. In addition, the company is frequently named one of the 100 Best Companies for Working Mothers by Working Mother magazine.

In January 2015, Intel announced the investment of $300 million over the next five years to enhance gender and racial diversity in their own company as well as the technology industry as a whole.[237][238][239][240][241]

In February 2016, Intel released its Global Diversity & Inclusion 2015 Annual Report.[242] The male-female mix of US employees was reported as 75.2% men and 24.8% women. For US employees in technical roles, the mix was reported as 79.8% male and 20.1% female.[242] NPR reports that Intel is facing a retention problem (particularly for African Americans), not just a pipeline problem.[243]

Economic impact in Oregon in 2009[edit]

In 2011, ECONorthwest conducted an economic impact analysis of Intel’s economic contribution to the state of Oregon. The report found that in 2009 «the total economic impacts attributed to Intel’s operations, capital spending, contributions and taxes amounted to almost $14.6 billion in activity, including $4.3 billion in personal income and 59,990 jobs».[244] Through multiplier effects, every 10 Intel jobs supported, on average, was found to create 31 jobs in other sectors of the economy.[245]

Intel Israel[edit]

Intel has been operating in the State of Israel since Dov Frohman founded the Israeli branch of the company in 1974 in a small office in Haifa. Intel Israel currently has development centers in Haifa, Jerusalem and Petah Tikva, and has a manufacturing plant in the Kiryat Gat industrial park that develops and manufactures microprocessors and communications products. Intel employed about 10,000 employees in Israel in 2013. Maxine Fesberg has been the CEO of Intel Israel since 2007 and the Vice President of Intel Global. In December 2016, Fesberg announced her resignation, her position of chief executive officer (CEO) has been filled by Yaniv Gerti since January 2017.

Key acquisitions and investments (2010–present)[edit]

In 2010, Intel purchased McAfee, a manufacturer of computer security technology, for $7.68 billion.[246] As a condition for regulatory approval of the transaction, Intel agreed to provide rival security firms with all necessary information that would allow their products to use Intel’s chips and personal computers.[247] After the acquisition, Intel had about 90,000 employees, including about 12,000 software engineers.[248] In September 2016, Intel sold a majority stake in its computer-security unit to TPG Capital, reversing the five-year-old McAfee acquisition.[249]

In August 2010, Intel and Infineon Technologies announced that Intel would acquire Infineon’s Wireless Solutions business.[250] Intel planned to use Infineon’s technology in laptops, smart phones, netbooks, tablets and embedded computers in consumer products, eventually integrating its wireless modem into Intel’s silicon chips.[251]

In March 2011, Intel bought most of the assets of Cairo-based SySDSoft.[252]

In July 2011, Intel announced that it had agreed to acquire Fulcrum Microsystems Inc., a company specializing in network switches.[253] The company used to be included on the EE Times list of 60 Emerging Startups.[253]

In October 2011, Intel reached a deal to acquire Telmap, an Israeli-based navigation software company. The purchase price was not disclosed, but Israeli media reported values around $300 million to $350 million.[254]

In July 2012, Intel agreed to buy 10% of the shares of ASML Holding NV for $2.1 billion and another $1 billion for 5% of the shares that need shareholder approval to fund relevant research and development efforts, as part of a EUR3.3 billion ($4.1 billion) deal to accelerate the development of 450-millimeter wafer technology and extreme ultra-violet lithography by as much as two years.[255]

In July 2013, Intel confirmed the acquisition of Omek Interactive, an Israeli company that makes technology for gesture-based interfaces, without disclosing the monetary value of the deal. An official statement from Intel read: «The acquisition of Omek Interactive will help increase Intel’s capabilities in the delivery of more immersive perceptual computing experiences.» One report estimated the value of the acquisition between US$30 million and $50 million.[256]

The acquisition of a Spanish natural language recognition startup, Indisys was announced in September 2013. The terms of the deal were not disclosed but an email from an Intel representative stated: «Intel has acquired Indisys, a privately held company based in Seville, Spain. The majority of Indisys employees joined Intel. We signed the agreement to acquire the company on May 31 and the deal has been completed.» Indysis explains that its artificial intelligence (AI) technology «is a human image, which converses fluently and with common sense in multiple languages and also works in different platforms».[257]

In December 2014, Intel bought PasswordBox.[258]

In January 2015, Intel purchased a 30% stake in Vuzix, a smart glasses manufacturer. The deal was worth $24.8 million.[259]

In February 2015, Intel announced its agreement to purchase German network chipmaker Lantiq, to aid in its expansion of its range of chips in devices with Internet connection capability.[260]

In June 2015, Intel announced its agreement to purchase FPGA design company Altera for $16.7 billion, in its largest acquisition to date.[261] The acquisition completed in December 2015.[262]

In October 2015, Intel bought cognitive computing company Saffron Technology for an undisclosed price.[263]

In August 2016, Intel purchased deep-learning startup Nervana Systems for over $400 million.[264]

In December 2016, Intel acquired computer vision startup Movidius for an undisclosed price.[265]

In March 2017, Intel announced that they had agreed to purchase Mobileye, an Israeli developer of «autonomous driving» systems for US$15.3 billion.[266]

In June 2017, Intel Corporation announced an investment of over ₹1,100 crore (US$140 million) for its upcoming Research and Development (R&D) centre in Bangalore, India.[267]

In January 2019, Intel announced an investment of over $11 billion on a new Israeli chip plant, as told by the Israeli Finance Minister.[268]

In November 2021, Intel recruited some of the employees of the Centaur Technology division from VIA Technologies, a deal worth $125 million, and effectively acquiring the talent and knowhow of their x86 division.[269][270] VIA retained the x86 licence and associated patents, and its Zhaoxin CPU joint-venture continues.[271]

In December 2021, Intel said it will invest $7.1 billion to build a new chip-packaging and testing factory in Malaysia. The new investment will expand the operations of its Malaysian subsidiary across Penang and Kulim, creating more than 4,000 new Intel jobs and more than 5,000 local construction jobs.[272]

In December 2021, Intel announced its plan to take Mobileye automotive unit via an IPO of newly issued stock in 2022, maintaining its majority ownership of the company.[273]

In May 2022, Intel announced that they have acquired Finnish graphics technology firm Siru innovations. The firm founded by ex-AMD Qualcomm mobile GPU engineers, is focused on developing software and silicon building blocks for GPU’s made by other companies and is set to join Intel’s fledgling Accelerated Computing Systems and Graphics Group.[274]

In May 2022, it was announced that Ericsson and Intel, are pooling research and development to create high-performing Cloud RAN solutions. The organisations have pooled to launch a tech hub in California, USA. The hub focuses on the benefits that Ericsson Cloud RAN and Intel technology can bring to: improving energy efficiency and network performance, reducing time to market, and monetizing new business opportunities such as enterprise applications.[275]

Ultrabook fund (2011)[edit]

In 2011, Intel Capital announced a new fund to support startups working on technologies in line with the company’s concept for next generation notebooks.[276] The company is setting aside a $300 million fund to be spent over the next three to four years in areas related to ultrabooks.[276] Intel announced the ultrabook concept at Computex in 2011. The ultrabook is defined as a thin (less than 0.8 inches [~2 cm] thick[277]) notebook that utilizes Intel processors[277] and also incorporates tablet features such as a touch screen and long battery life.[276][277]

At the Intel Developers Forum in 2011, four Taiwan ODMs showed prototype ultrabooks that used Intel’s Ivy Bridge chips.[278] Intel plans to improve power consumption of its chips for ultrabooks, like new Ivy Bridge processors in 2013, which will only have 10W default thermal design power.[279]

Intel’s goal for Ultrabook’s price is below $1000;[277] however, according to two presidents from Acer and Compaq, this goal will not be achieved if Intel does not lower the price of its chips.[280]

Open source support[edit]

Intel has a significant participation in the open source communities since 1999.[281][self-published source] For example, in 2006 Intel released MIT-licensed X.org drivers for their integrated graphic cards of the i965 family of chipsets. Intel released FreeBSD drivers for some networking cards,[282] available under a BSD-compatible license,[283] which were also ported to OpenBSD.[283] Binary firmware files for non-wireless Ethernet devices were also released under a BSD licence allowing free redistribution.[284] Intel ran the Moblin project until April 23, 2009, when they handed the project over to the Linux Foundation. Intel also runs the LessWatts.org campaigns.[285]