This article is about the social media service. For its owner, formerly known as Facebook, Inc., see Meta Platforms.

|

|

|

Screenshot Mark Zuckerberg’s profile (viewed when logged out) |

|

|

Type of site |

Social networking service Publisher |

|---|---|

| Available in | 112 languages[1] |

|

List of languages Multilingual |

|

| Founded | February 4, 2004; 19 years ago in Cambridge, Massachusetts |

| Area served | Worldwide, except blocking countries |

| Owner | Meta Platforms |

| Founder(s) |

|

| CEO | Mark Zuckerberg |

| URL | facebook.com |

| Registration | Required (to do any activity) |

| Users | |

| Launched | February 4, 2004; 19 years ago |

| Current status | Active |

| Written in | C++, Hack (as HHVM) |

| [3][4][5] |

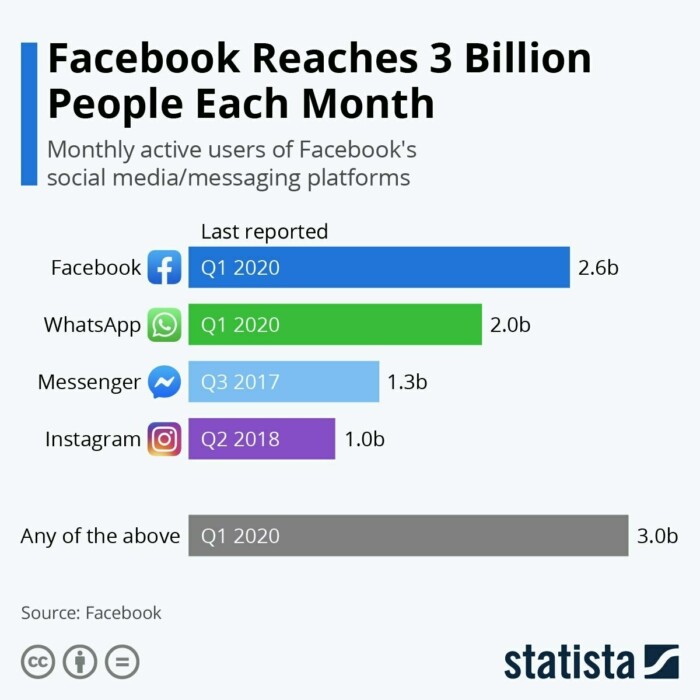

Facebook is an online social media and social networking service owned by American company Meta Platforms. Founded in 2004 by Mark Zuckerberg with fellow Harvard College students and roommates Eduardo Saverin, Andrew McCollum, Dustin Moskovitz, and Chris Hughes, its name comes from the face book directories often given to American university students. Membership was initially limited to Harvard students, gradually expanding to other North American universities and, since 2006, anyone over 13 years old. As of July 2022, Facebook claimed 2.93 billion monthly active users,[6] and ranked third worldwide among the most visited websites.[7] It was the most downloaded mobile app of the 2010s.[8]

Facebook can be accessed from devices with Internet connectivity, such as personal computers, tablets and smartphones. After registering, users can create a profile revealing information about themselves. They can post text, photos and multimedia which are shared with any other users who have agreed to be their «friend» or, with different privacy settings, publicly. Users can also communicate directly with each other with Facebook Messenger, join common-interest groups, and receive notifications on the activities of their Facebook friends and the pages they follow.

The subject of numerous controversies, Facebook has often been criticized over issues such as user privacy (as with the Cambridge Analytica data scandal), political manipulation (as with the 2016 U.S. elections) and mass surveillance.[9] Posts originating from the Facebook page of Breitbart News, a media organization previously affiliated with Cambridge Analytica,[10] are currently among the most widely shared political content on Facebook.[11][12][13][14][15] Facebook has also been subject to criticism over psychological effects such as addiction and low self-esteem, and various controversies over content such as fake news, conspiracy theories, copyright infringement, and hate speech.[16] Commentators have accused Facebook of willingly facilitating the spread of such content,[17][18][19][20][21][22] as well as exaggerating its number of users to appeal to advertisers.[23]

History

2003–2006: Thefacebook, Thiel investment, and name change

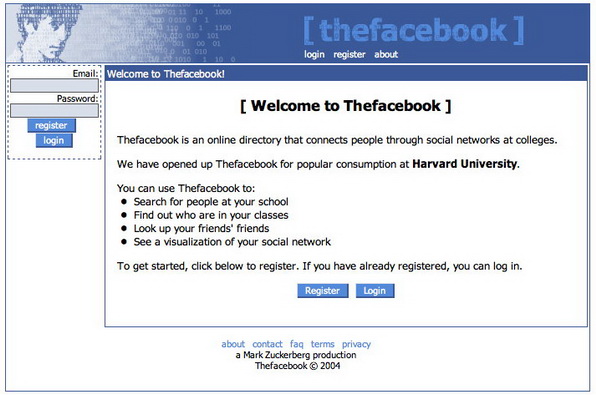

Original layout and name of Thefacebook in 2004, showing Al Pacino’s face superimposed with binary numbers as Facebook’s original logo, designed by co-founder Andrew McCollum[24]

Zuckerberg built a website called «Facemash» in 2003 while attending Harvard University. The site was comparable to Hot or Not and used «photos compiled from the online face books of nine Houses, placing two next to each other at a time and asking users to choose the «hotter» person».[25] Facemash attracted 450 visitors and 22,000 photo-views in its first four hours.[26] The site was sent to several campus group listservs, but was shut down a few days later by Harvard administration. Zuckerberg faced expulsion and was charged with breaching security, violating copyrights and violating individual privacy. Ultimately, the charges were dropped.[25] Zuckerberg expanded on this project that semester by creating a social study tool. He uploaded art images, each accompanied by a comments section, to a website he shared with his classmates.[27]

A «face book» is a student directory featuring photos and personal information.[26] In 2003, Harvard had only a paper version[28] along with private online directories.[25][29] Zuckerberg told The Harvard Crimson, «Everyone’s been talking a lot about a universal face book within Harvard. … I think it’s kind of silly that it would take the University a couple of years to get around to it. I can do it better than they can, and I can do it in a week.»[29] In January 2004, Zuckerberg coded a new website, known as «TheFacebook», inspired by a Crimson editorial about Facemash, stating, «It is clear that the technology needed to create a centralized Website is readily available … the benefits are many.» Zuckerberg met with Harvard student Eduardo Saverin, and each of them agreed to invest $1,000 ($1,435 in 2021 dollars[30]) in the site.[31] On February 4, 2004, Zuckerberg launched «TheFacebook», originally located at thefacebook.com.[32]

Six days after the site launched, Harvard seniors Cameron Winklevoss, Tyler Winklevoss, and Divya Narendra accused Zuckerberg of intentionally misleading them into believing that he would help them build a social network called HarvardConnection.com. They claimed that he was instead using their ideas to build a competing product.[33] The three complained to the Crimson and the newspaper began an investigation. They later sued Zuckerberg, settling in 2008[34] for 1.2 million shares (worth $300 million ($354 million in 2021 dollars[30]) at Facebook’s IPO).[35]

Membership was initially restricted to students of Harvard College. Within a month, more than half the undergraduates had registered.[36] Dustin Moskovitz, Andrew McCollum, and Chris Hughes joined Zuckerberg to help manage the growth of the website.[37] In March 2004, Facebook expanded to Columbia, Stanford and Yale.[38] It then became available to all Ivy League colleges, Boston University, NYU, MIT, and successively most universities in the United States and Canada.[39][40]

In mid-2004, Napster co-founder and entrepreneur Sean Parker—an informal advisor to Zuckerberg—became company president.[41] In June 2004, the company moved to Palo Alto, California.[42] It received its first investment later that month from PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel.[43] In 2005, the company dropped «the» from its name after purchasing the domain name Facebook.com for US$200,000 ($277,492 in 2021 dollars[30]).[44] The domain had belonged to AboutFace Corporation.

In May 2005, Accel Partners invested $12.7 million ($17.6 million in 2021 dollars[30]) in Facebook, and Jim Breyer[45] added $1 million ($1.39 million in 2021 dollars[30]) of his own money. A high-school version of the site launched in September 2005.[46] Eligibility expanded to include employees of several companies, including Apple Inc. and Microsoft.[47]

2006–2012: Public access, Microsoft alliance, and rapid growth

In May 2006, Facebook hired its first intern, Julie Zhuo.[48] After a month, Zhuo was hired as a full-time engineer.[48] On September 26, 2006, Facebook opened to everyone at least 13 years old with a valid email address.[49][50][51] By late 2007, Facebook had 100,000 pages on which companies promoted themselves.[52] Organization pages began rolling out in May 2009.[53] On October 24, 2007, Microsoft announced that it had purchased a 1.6% share of Facebook for $240 million ($314 million in 2021 dollars[30]), giving Facebook a total implied value of around $15 billion ($19.6 billion in 2021 dollars[30]). Microsoft’s purchase included rights to place international advertisements.[54][55]

In May 2007, at the first f8 developers conference, Facebook announced the launch of the Facebook Developer Platform, providing a framework for software developers to create applications that interact with core Facebook features. By the second annual f8 developers conference on July 23, 2008, the number of applications on the platform had grown to 33,000, and the number of registered developers had exceeded 400,000.[56]

The website won awards such as placement into the «Top 100 Classic Websites» by PC Magazine in 2007,[57] and winning the «People’s Voice Award» from the Webby Awards in 2008.[58]

On July 20, 2008, Facebook introduced «Facebook Beta», a significant redesign of its user interface on selected networks. The Mini-Feed and Wall were consolidated, profiles were separated into tabbed sections, and an effort was made to create a cleaner look.[59] Facebook began migrating users to the new version in September 2008.[60]

In October 2008, Facebook announced that its international headquarters would locate in Dublin, Ireland.[61] In September 2009, Facebook said that it had achieved positive cash flow for the first time.[62] A January 2009 Compete.com study ranked Facebook the most used social networking service by worldwide monthly active users.[63][better source needed] China blocked Facebook in 2009 following the Ürümqi riots.[64]

In 2010, Facebook won the Crunchie «Best Overall Startup Or Product» award[65] for the third year in a row.[66]

The company announced 500 million users in July 2010.[67] Half of the site’s membership used Facebook daily, for an average of 34 minutes, while 150 million users accessed the site from mobile devices. A company representative called the milestone a «quiet revolution.»[68] In October 2010 groups were introduced.[69] In November 2010, based on SecondMarket Inc. (an exchange for privately held companies’ shares), Facebook’s value was $41 billion ($50.9 billion in 2021 dollars[30]). The company had slightly surpassed eBay to become the third largest American web company after Google and Amazon.com.[70][71]

On November 15, 2010, Facebook announced it had acquired the domain name fb.com from the American Farm Bureau Federation for an undisclosed amount. On January 11, 2011, the Farm Bureau disclosed $8.5 million ($10.2 million in 2021 dollars[30]) in «domain sales income», making the acquisition of FB.com one of the ten highest domain sales in history.[72]

In February 2011, Facebook announced plans to move its headquarters to the former Sun Microsystems campus in Menlo Park, California.[73][74] In March 2011, it was reported that Facebook was removing about 20,000 profiles daily for violations such as spam, graphic content and underage use, as part of its efforts to boost cyber security.[75] Statistics showed that Facebook reached one trillion page views in the month of June 2011, making it the most visited website tracked by DoubleClick.[76][77] According to a Nielsen study, Facebook had in 2011 become the second-most accessed website in the U.S. behind Google.[78][79]

2012–2013: IPO, lawsuits, and one billion active users

In March 2012, Facebook announced App Center, a store selling applications that operate via the website. The store was to be available on iPhones, Android devices, and for mobile web users.[80]

Billboard on the Thomson Reuters building welcomes Facebook to NASDAQ, May 2012

Facebook’s initial public offering came on May 17, 2012, at a share price of US$38 ($45.00 in 2021 dollars[30]). The company was valued at $104 billion ($123 billion in 2021 dollars[30]), the largest valuation to that date.[81][82][83] The IPO raised $16 billion ($18.9 billion in 2021 dollars[30]), the third-largest in U.S. history, after Visa Inc. in 2008 and AT&T Wireless in 2000.[84][85] Based on its 2012 income of $5 billion ($5.9 billion in 2021 dollars[30]), Facebook joined the Fortune 500 list for the first time in May 2013, ranked 462.[86] The shares set a first-day record for trading volume of an IPO (460 million shares).[87] The IPO was controversial given the immediate price declines that followed,[88][89][90][91] and was the subject of lawsuits,[92] while SEC and FINRA both launched investigations.[93]

Zuckerberg announced at the start of October 2012 that Facebook had one billion monthly active users,[94] including 600 million mobile users, 219 billion photo uploads and 140 billion friend connections.[95]

2013–2014: Site developments, A4AI, and 10th anniversary

On January 15, 2013, Facebook announced Facebook Graph Search, which provides users with a «precise answer», rather than a link to an answer by leveraging data present on its site.[96] Facebook emphasized that the feature would be «privacy-aware», returning results only from content already shared with the user.[97] On April 3, 2013, Facebook unveiled Facebook Home, a user-interface layer for Android devices offering greater integration with the site. HTC announced HTC First, a phone with Home pre-loaded.[98]

On April 15, 2013, Facebook announced an alliance across 19 states with the National Association of Attorneys General, to provide teenagers and parents with information on tools to manage social networking profiles.[99] On April 19 Facebook modified its logo to remove the faint blue line at the bottom of the «F» icon. The letter F moved closer to the edge of the box.[100]

Following a campaign by 100 advocacy groups, Facebook agreed to update its policy on hate speech. The campaign highlighted content promoting domestic violence and sexual violence against women and led 15 advertisers to withdraw, including Nissan UK, House of Burlesque, and Nationwide UK. The company initially stated, «while it may be vulgar and offensive, distasteful content on its own does not violate our policies».[101] It took action on May 29.[102]

On June 12, Facebook announced that it was introducing clickable hashtags to help users follow trending discussions, or search what others are talking about on a topic.[103] San Mateo County, California, became the top wage-earning county in the country after the fourth quarter of 2012 because of Facebook. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that the average salary was 107% higher than the previous year, at $168,000 a year ($198,293 in 2021 dollars[30]), more than 50% higher than the next-highest county, New York County (better known as Manhattan), at roughly $110,000 a year ($129,835 in 2021 dollars[30]).[104]

Facebook joined Alliance for Affordable Internet (A4AI) in October, as it launched. The A4AI is a coalition of public and private organizations that includes Google, Intel and Microsoft. Led by Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the A4AI seeks to make Internet access more affordable to ease access in the developing world.[105]

The company celebrated its 10th anniversary during the week of February 3, 2014.[106] In January 2014, over one billion users connected via a mobile device.[107] As of June, mobile accounted for 62% of advertising revenue, an increase of 21% from the previous year.[108] By September Facebook’s market capitalization had exceeded $200 billion ($229 billion in 2021 dollars[30]).[109][110][111]

Zuckerberg participated in a Q&A session at Tsinghua University in Beijing, China, on October 23, where he attempted to converse in Mandarin. Zuckerberg hosted visiting Chinese politician Lu Wei, known as the «Internet czar» for his influence in China’s online policy, on December 8.[112][113][114]

2015–2020: Algorithm revision; fake news

As of 2015, Facebook’s algorithm was revised in an attempt to filter out false or misleading content, such as fake news stories and hoaxes. It relied on users who flag a story accordingly. Facebook maintained that satirical content should not be intercepted.[115] The algorithm was accused of maintaining a «filter bubble», where material the user disagrees with[116] and posts with few likes would be deprioritized.[117] In November, Facebook extended paternity leave from 4 weeks to 4 months.[118]

On April 12, 2016, Zuckerberg outlined his 10-year vision, which rested on three main pillars: artificial intelligence, increased global connectivity, and virtual and augmented reality.[119] In July, a US$1 billion suit was filed against the company alleging that it permitted Hamas to use it to perform assaults that cost the lives of four people.[120] Facebook released its blueprints of Surround 360 camera on GitHub under an open-source license.[121] In September, it won an Emmy for its animated short «Henry».[122] In October, Facebook announced a fee-based communications tool called Workplace that aims to «connect everyone» at work. Users can create profiles, see updates from co-workers on their news feed, stream live videos and participate in secure group chats.[123]

Following the 2016 U.S. presidential election, Facebook announced that it would combat fake news by using fact checkers from sites like FactCheck.org and Associated Press (AP), making reporting hoaxes easier through crowdsourcing, and disrupting financial incentives for abusers.[124]

On January 17, 2017, Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg planned to open Station F, a startup incubator campus in Paris, France.[126] On a six-month cycle, Facebook committed to work with ten to 15 data-driven startups there.[127] On April 18, Facebook announced the beta launch of Facebook Spaces at its annual F8 developer conference.[128] Facebook Spaces is a virtual reality version of Facebook for Oculus VR goggles. In a virtual and shared space, users can access a curated selection of 360-degree photos and videos using their avatar, with the support of the controller. Users can access their own photos and videos, along with media shared on their newsfeed.[129] In September, Facebook announced it would spend up to US$1 billion on original shows for its Facebook Watch platform.[130] On October 16, it acquired the anonymous compliment app tbh, announcing its intention to leave the app independent.[131][132][133][134]

In October 2017, Facebook expanded its work with Definers Public Affairs, a PR firm that had originally been hired to monitor press coverage of the company to address concerns primarily regarding Russian meddling, then mishandling of user data by Cambridge Analytica, hate speech on Facebook, and calls for regulation.[135] Company spokesman Tim Miller stated that a goal for tech firms should be to «have positive content pushed out about your company and negative content that’s being pushed out about your competitor». Definers claimed that George Soros was the force behind what appeared to be a broad anti-Facebook movement, and created other negative media, along with America Rising, that was picked up by larger media organisations like Breitbart News.[135][136] Facebook cut ties with the agency in late 2018, following public outcry over their association.[137]

In May 2018 at F8, the company announced it would offer its own dating service. Shares in competitor Match Group fell by 22%.[138] Facebook Dating includes privacy features and friends are unable to view their friends’ dating profile.[139] In July, Facebook was charged £500,000 by UK watchdogs for failing to respond to data erasure requests.[140] On July 18, Facebook established a subsidiary named Lianshu Science & Technology in Hangzhou City, China, with $30 million ($32.4 million in 2021 dollars[30]) of capital. All its shares are held by Facebook Hong.[141] Approval of the registration of the subsidiary was then withdrawn, due to a disagreement between officials in Zhejiang province and the Cyberspace Administration of China.[142] On July 26, Facebook became the first company to lose over $100 billion ($108 billion in 2021 dollars[30]) worth of market capitalization in one day, dropping from nearly $630 billion to $510 billion after disappointing sales reports.[143][144] On July 31, Facebook said that the company had deleted 17 accounts related to the 2018 U.S. midterm elections. On September 19, Facebook announced that, for news distribution outside the United States, it would work with U.S. funded democracy promotion organizations, International Republican Institute and the National Democratic Institute, which are loosely affiliated with the Republican and Democratic parties.[145] Through the Digital Forensic Research Lab Facebook partners with the Atlantic Council, a NATO-affiliated think tank.[145] In November, Facebook launched smart displays branded Portal and Portal Plus (Portal+). They support Amazon’s Alexa (intelligent personal assistant service). The devices include video chat function with Facebook Messenger.[146][147]

In August 2018, a lawsuit was filed in Oakland, California claiming that Facebook created fake accounts in order to inflate its user data and appeal to advertisers in the process.[23]

In January 2019, the 10-year challenge was started[148] asking users to post a photograph of themselves from 10 years ago (2009) and a more recent photo.[149]

Criticized for its role in vaccine hesitancy, Facebook announced in March 2019 that it would provide users with «authoritative information» on the topic of vaccines.[150]

A study in the journal Vaccine[151] of advertisements posted in the three months prior to that found that 54% of the anti-vaccine advertisements on Facebook were placed by just two organisations funded by well-known anti-vaccination activists.[152] The Children’s Health Defense / World Mercury Project chaired by Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Stop Mandatory Vaccination, run by campaigner Larry Cook, posted 54% of the advertisements. The ads often linked to commercial products, such as natural remedies and books.

On March 14, the Huffington Post reported that Facebook’s PR agency had paid someone to tweak Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg’s Wikipedia page, as well as adding a page for the global head of PR, Caryn Marooney.[153]

In March 2019, the perpetrator of the Christchurch mosque shootings in New Zealand used Facebook to stream live footage of the attack as it unfolded. Facebook took 29 minutes to detect the livestreamed video, which was eight minutes longer than it took police to arrest the gunman. About 1.3m copies of the video were blocked from Facebook but 300,000 copies were published and shared. Facebook has promised changes to its platform; spokesman Simon Dilner told Radio New Zealand that it could have done a better job. Several companies, including the ANZ and ASB banks, have stopped advertising on Facebook after the company was widely condemned by the public.[154] Following the attack, Facebook began blocking white nationalist, white supremacist, and white separatist content, saying that they could not be meaningfully separated. Previously, Facebook had only blocked overtly supremacist content. The older policy had been condemned by civil rights groups, who described these movements as functionally indistinct.[155][156] Further bans were made in mid-April 2019, banning several British far-right organizations and associated individuals from Facebook, and also banning praise or support for them.[157][158]

NTJ’s member Moulavi Zahran Hashim, a radical Islamist imam believed to be the mastermind behind the 2019 Sri Lanka Easter bombings, preached on a pro-ISIL Facebook account, known as «Al-Ghuraba» media.[159][160]

On May 2, 2019, at F8, the company announced its new vision with the tagline «the future is private».[161] A redesign of the website and mobile app was introduced, dubbed as «FB5».[162] The event also featured plans for improving groups,[163] a dating platform,[164] end-to-end encryption on its platforms,[165] and allowing users on Messenger to communicate directly with WhatsApp and Instagram users.[166][167]

On July 31, 2019, Facebook announced a partnership with University of California, San Francisco to build a non-invasive, wearable device that lets people type by simply imagining themselves talking.[168]

On August 13, 2019, it was revealed that Facebook had enlisted hundreds of contractors to create and obtain transcripts of the audio messages of users.[169][170][171] This was especially common of Facebook Messenger, where the contractors frequently listened to and transcribed voice messages of users.[171] After this was first reported on by Bloomberg News, Facebook released a statement confirming the report to be true,[170] but also stated that the monitoring program was now suspended.[170]

On September 5, 2019, Facebook launched Facebook Dating in the United States. This new application allows users to integrate their Instagram posts in their dating profile.[172]

Facebook News, which features selected stories from news organizations, was launched on October 25.[173] Facebook’s decision to include far-right website Breitbart News as a «trusted source» was negatively received.[174][175]

On November 17, 2019, the banking data for 29,000 Facebook employees was stolen from a payroll worker’s car. The data was stored on unencrypted hard drives and included bank account numbers, employee names, the last four digits of their social security numbers, salaries, bonuses, and equity details. The company didn’t realize the hard drives were missing until November 20. Facebook confirmed that the drives contained employee information on November 29. Employees weren’t notified of the break-in until December 13, 2019.[176]

On March 10, 2020, Facebook appointed two new directors Tracey Travis and Nancy Killefer to their board of members.[177]

In June 2020, several major companies including Adidas, Aviva, Coca-Cola, Ford, HP, InterContinental Hotels Group, Mars, Starbucks, Target, and Unilever, announced they would pause adverts on Facebook for July in support of the Stop Hate For Profit campaign which claimed the company was not doing enough to remove hateful content.[178] The BBC noted that this was unlikely to affect the company as most of Facebook’s advertising revenue comes from small- to medium-sized businesses.[179]

On August 14, 2020, Facebook started integrating the direct messaging service of Instagram with its own Messenger for both iOS and Android devices. After the update, an update screen is said to pop up on Instagram’s mobile app with the following message, «There’s a New Way to Message on Instagram» with a list of additional features. As part of the update, the regular DM icon on the top right corner of Instagram will be replaced by the Facebook Messenger logo.[180]

On September 15, 2020, Facebook launched a climate science information centre to promote authoritative voices on climate change and provide access of «factual and up-to-date» information on climate science. It featured facts, figures and data from organizations, including the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Met Office, UN Environment Programme (UNEP), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and World Meteorological Organization (WMO), with relevant news posts.[181]

After the 2020 U.S. presidential election, Facebook temporarily increased the weight of ecosystem quality in its news feed algorithm.[182]

2020–present: FTC lawsuit, corporate re-branding, shut down of facial recognition technology, ease of policy

Facebook was sued by the Federal Trade Commission as well as a coalition of several states for illegal monopolization and antitrust. The FTC and states sought the courts to force Facebook to sell its subsidiaries WhatsApp and Instagram.[183][184] The suits were dismissed by a federal judge on June 28, 2021, who stated that there was not enough evidence brought in the suit to determine Facebook to be a monopoly at this point, though allowed the FTC to amend its case to include additional evidence.[185] In its amended filings in August 2021, the FTC asserted that Facebook had been a monopoly in the area of personal social networks since 2011, distinguishing Facebook’s activities from social media services like TikTok that broadcast content without necessarily limiting that message to intended recipients.[186]

In response to the proposed bill in the Australian Parliament for a News Media Bargaining Code, on February 17, 2021, Facebook blocked Australian users from sharing or viewing news content on its platform, as well as pages of some government, community, union, charity, political, and emergency services.[187] The Australian government strongly criticised the move, saying it demonstrated the «immense market power of these digital social giants».[188]

On February 22, Facebook said it reached an agreement with the Australian government that would see news returning to Australian users in the coming days. As part of this agreement, Facebook and Google can avoid the News Media Bargaining Code adopted on February 25 if they «reach a commercial bargain with a news business outside the Code».[189][190][191]

Facebook has been accused of removing and shadow banning content that spoke either in favor of protesting Indian farmers or against Narendra Modi’s government.[192][193][194] India-based employees of Facebook are at risk of arrest.[195]

On February 27, 2021, Facebook announced Facebook BARS app for rappers.[196]

On June 29, 2021, Facebook announced Bulletin, a platform for independent writers.[197][198] Unlike competitors such as Substack, Facebook would not take a cut of subscription fees of writers using that platform upon its launch, like Malcolm Gladwell and Mitch Albom. According to The Washington Post technology writer Will Oremus, the move was criticized by those who viewed it as an tactic intended by Facebook to force those competitors out of business.[199]

In October 2021, owner Facebook, Inc. changed its company name to Meta Platforms, Inc., or simply «Meta», as it shifts its focus to building the «metaverse». This change does not affect the name of the Facebook social networking service itself, instead being similar to the creation of Alphabet as Google’s parent company in 2015.[200]

In November 2021, Facebook stated it would stop targeting ads based on data related to health, race, ethnicity, political beliefs, religion and sexual orientation. The change will occur in January and will affect all apps owned by Meta Platforms.[201]

In February 2022, Facebook’s daily active users dropped for the first time in its 18-year history. According to Facebook’s parent Meta, DAUs dropped to 1.929 billion in the three months ending in December, down from 1.930 billion the previous quarter. Furthermore, the company warned that revenue growth would slow due to competition from TikTok and YouTube, as well as advertisers cutting back on spending.[202]

Analysts predict a «death spiral» for facebook stock as users leave while ad impressions increase, as the company chases revenue.[203]

On March 10, 2022, Facebook announced that it will temporarily ease rules to allow violent speech against ‘Russian invaders’.[204] Russia then banned all Meta services, including Instagram.[205]

October 4, 2021, global service outage

On October 4, 2021, Facebook had its worst outage since 2008. The outage was global in scope, and took down all Facebook properties, including Instagram and WhatsApp, from approximately 15:39 UTC to 22:05 UTC, and affected roughly three billion users.[206][207][208] Security experts identified the problem as a BGP withdrawal of all of the IP routes to their Domain Name (DNS) servers which were all self-hosted at the time.[209][210] The outage also affected all internal communications systems used by Facebook employees, which disrupted restoration efforts.[210]

Shutdown of facial recognition

On November 2, 2021, Facebook announced it would shut down its facial recognition technology and delete the data on over a billion users.[211] Meta later announced plans to implement the technology as well as other biometric systems in its future products, such as the metaverse.[212]

The shutdown of the technology will reportedly also stop Facebook’s automated alt text system, used to transcribe media on the platform for visually impaired users.[212]

In February 2023, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg announced that Meta would start selling blue «verified» badges on Instagram and Facebook.[213]

Website

Profile shown on Thefacebook in 2005

Previous Facebook logo in use from August 23, 2005, until July 1, 2015

Technical aspects

|

|

This section’s factual accuracy may be compromised due to out-of-date information. The reason given is: Facebook no longer uses HipHop for PHP. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (August 2020) |

The website’s primary color is blue as Zuckerberg is red–green colorblind, a realization that occurred after a test undertaken around 2007.[214][215] Facebook is built in PHP, compiled with HipHop for PHP, a «source code transformer» built by Facebook engineers that turns PHP into C++.[216] The deployment of HipHop reportedly reduced average CPU consumption on Facebook servers by 50%.[217]

2012 architecture

Facebook is developed as one monolithic application. According to an interview in 2012 with Facebook build engineer Chuck Rossi, Facebook compiles into a 1.5 GB binary blob which is then distributed to the servers using a custom BitTorrent-based release system. Rossi stated that it takes about 15 minutes to build and 15 minutes to release to the servers. The build and release process has zero downtime. Changes to Facebook are rolled out daily.[217]

Facebook used a combination platform based on HBase to store data across distributed machines. Using a tailing architecture, events are stored in log files, and the logs are tailed. The system rolls these events up and writes them to storage. The user interface then pulls the data out and displays it to users. Facebook handles requests as AJAX behavior. These requests are written to a log file using Scribe (developed by Facebook).[218]

Data is read from these log files using Ptail, an internally built tool to aggregate data from multiple Scribe stores. It tails the log files and pulls data out. Ptail data are separated into three streams and sent to clusters in different data centers (Plugin impression, News feed impressions, Actions (plugin + news feed)). Puma is used to manage periods of high data flow (Input/Output or IO). Data is processed in batches to lessen the number of times needed to read and write under high demand periods. (A hot article generates many impressions and news feed impressions that cause huge data skews.) Batches are taken every 1.5 seconds, limited by memory used when creating a hash table.[218]

Data is then output in PHP format. The backend is written in Java. Thrift is used as the messaging format so PHP programs can query Java services. Caching solutions display pages more quickly. The data is then sent to MapReduce servers where it is queried via Hive. This serves as a backup as the data can be recovered from Hive.[218]

Content delivery network (CDN)

Facebook uses its own content delivery network or «edge network» under the domain fbcdn.net for serving static data.[219][220] Until the mid 2010s, Facebook also relied on Akamai for CDN services.[221][222][223]

Hack programming language

On March 20, 2014, Facebook announced a new open-source programming language called Hack. Before public release, a large portion of Facebook was already running and «battle tested» using the new language.[224]

User profile/personal timeline

Facebook login/signup screen

Each registered user on Facebook has a personal profile that shows their posts and content.[225] The format of individual user pages was revamped in September 2011 and became known as «Timeline», a chronological feed of a user’s stories,[226][227] including status updates, photos, interactions with apps and events.[228] The layout let users add a «cover photo».[228] Users were given more privacy settings.[228] In 2007, Facebook launched Facebook Pages for brands and celebrities to interact with their fanbases.[229][230] 100,000 Pages[further explanation needed] launched in November.[231] In June 2009, Facebook introduced a «Usernames» feature, allowing users to choose a unique nickname used in the URL for their personal profile, for easier sharing.[232][233]

In February 2014, Facebook expanded the gender setting, adding a custom input field that allows users to choose from a wide range of gender identities. Users can also set which set of gender-specific pronoun should be used in reference to them throughout the site.[234][235][236] In May 2014, Facebook introduced a feature to allow users to ask for information not disclosed by other users on their profiles. If a user does not provide key information, such as location, hometown, or relationship status, other users can use a new «ask» button to send a message asking about that item to the user in a single click.[237][238]

News Feed

News Feed appears on every user’s homepage and highlights information including profile changes, upcoming events and friends’ birthdays.[239] This enabled spammers and other users to manipulate these features by creating illegitimate events or posting fake birthdays to attract attention to their profile or cause.[240] Initially, the News Feed caused dissatisfaction among Facebook users; some complained it was too cluttered and full of undesired information, others were concerned that it made it too easy for others to track individual activities (such as relationship status changes, events, and conversations with other users).[241] Zuckerberg apologized for the site’s failure to include appropriate privacy features. Users then gained control over what types of information are shared automatically with friends. Users are now able to prevent user-set categories of friends from seeing updates about certain types of activities, including profile changes, Wall posts and newly added friends.[242]

On February 23, 2010, Facebook was granted a patent[243] on certain aspects of its News Feed. The patent covers News Feeds in which links are provided so that one user can participate in the activity of another user.[244] The sorting and display of stories in a user’s News Feed is governed by the EdgeRank algorithm.[245]

The Photos application allows users to upload albums and photos.[246] Each album can contain 200 photos.[247] Privacy settings apply to individual albums. Users can «tag», or label, friends in a photo. The friend receives a notification about the tag with a link to the photo.[248] This photo tagging feature was developed by Aaron Sittig, now a Design Strategy Lead at Facebook, and former Facebook engineer Scott Marlette back in 2006 and was only granted a patent in 2011.[249][250]

On June 7, 2012, Facebook launched its App Center to help users find games and other applications.[251]

On May 13, 2015, Facebook in association with major news portals launched «Instant Articles» to provide news on the Facebook news feed without leaving the site.[252][253]

In January 2017, Facebook launched Facebook Stories for iOS and Android in Ireland. The feature, following the format of Snapchat and Instagram stories, allows users to upload photos and videos that appear above friends’ and followers’ News Feeds and disappear after 24 hours.[254]

On October 11, 2017, Facebook introduced the 3D Posts feature to allow for uploading interactive 3D assets.[255] On January 11, 2018, Facebook announced that it would change News Feed to prioritize friends/family content and de-emphasize content from media companies.[256]

In February 2020, Facebook announced it would spend $1 billion ($1.05 billion in 2021 dollars[30]) to license news material from publishers for the next three years; a pledge coming as the company falls under scrutiny from governments across the globe over not paying for news content appearing on the platform. The pledge would be in addition to the $600 million ($628 million in 2021 dollars[30]) paid since 2018 through deals with news companies such as The Guardian and Financial Times.[257][258][259]

In March and April 2021, in response to Apple announcing changes to its iOS device’s Identifier for Advertisers policy, which included requiring app developers to directly request to users the ability to track on an opt-in basis, Facebook purchased full-page newspaper advertisements attempting to convince users to allow tracking, highlighting the effects targeted ads have on small businesses.[260] Facebook’s efforts were ultimately unsuccessful, as Apple released iOS 14.5 in late April 2021, containing the feature for users in what has been deemed «App Tracking Transparency». Moreover, statistics from Verizon Communications subsidiary Flurry Analytics show 96% of all iOS users in the United States are not permitting tracking at all, and only 12% of worldwide iOS users are allowing tracking, which some news outlets deem «Facebook’s nightmare», among similar terms.[261][262][263][264] Despite the news, Facebook has stated that the new policy and software update would be «manageable».[265]

Like button

The «like» button, stylized as a «thumbs up» icon, was first enabled on February 9, 2009,[266] and enables users to easily interact with status updates, comments, photos and videos, links shared by friends, and advertisements. Once clicked by a user, the designated content is more likely to appear in friends’ News Feeds.[267][268] The button displays the number of other users who have liked the content.[269] The like button was extended to comments in June 2010.[270] In February 2016, Facebook expanded Like into «Reactions», choosing among five pre-defined emotions, including «Love», «Haha», «Wow», «Sad», or «Angry».[271][272][273][274] In late April 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, a new «Care» reaction was added.[275]

Instant messaging

Facebook Messenger is an instant messaging service and software application. It began as Facebook Chat in 2008,[276] was revamped in 2010[277] and eventually became a standalone mobile app in August 2011, while remaining part of the user page on browsers.[278]

Complementing regular conversations, Messenger lets users make one-to-one[279] and group[280] voice[281] and video calls.[282] Its Android app has integrated support for SMS[283] and «Chat Heads», which are round profile photo icons appearing on-screen regardless of what app is open,[284] while both apps support multiple accounts,[285] conversations with optional end-to-end encryption[286] and «Instant Games».[287] Some features, including sending money[288] and requesting transportation,[289] are limited to the United States.[288] In 2017, Facebook added «Messenger Day», a feature that lets users share photos and videos in a story-format with all their friends with the content disappearing after 24 hours;[290] Reactions, which lets users tap and hold a message to add a reaction through an emoji;[291] and Mentions, which lets users in group conversations type @ to give a particular user a notification.[291]

Businesses and users can interact through Messenger with features such as tracking purchases and receiving notifications, and interacting with customer service representatives. Third-party developers can integrate apps into Messenger, letting users enter an app while inside Messenger and optionally share details from the app into a chat.[292] Developers can build chatbots into Messenger, for uses such as news publishers building bots to distribute news.[293] The M virtual assistant (U.S.) scans chats for keywords and suggests relevant actions, such as its payments system for users mentioning money.[294][295] Group chatbots appear in Messenger as «Chat Extensions». A «Discovery» tab allows finding bots, and enabling special, branded QR codes that, when scanned, take the user to a specific bot.[296]

Privacy policy

See also: § Privacy

Facebook’s data policy outlines its policies for collecting, storing, and sharing user’s data.[297] Facebook enables users to control access to individual posts and their profile[298] through privacy settings.[299] The user’s name and profile picture (if applicable) are public.

Facebook’s revenue depends on targeted advertising, which involves analyzing user data to decide which ads to show each user. Facebook buys data from third parties, gathered from both online and offline sources, to supplement its own data on users. Facebook maintains that it does not share data used for targeted advertising with the advertisers themselves.[300] The company states:

«We provide advertisers with reports about the kinds of people seeing their ads and how their ads are performing, but we don’t share information that personally identifies you (information such as your name or email address that by itself can be used to contact you or identifies who you are) unless you give us permission. For example, we provide general demographic and interest information to advertisers (for example, that an ad was seen by a woman between the ages of 25 and 34 who lives in Madrid and likes software engineering) to help them better understand their audience. We also confirm which Facebook ads led you to make a purchase or take an action with an advertiser.»[297]

As of October 2021, Facebook claims it uses the following policy for sharing user data with third parties:

Apps, websites, and third-party integrations on or using our Products.

When you choose to use third-party apps, websites, or other services that use, or are integrated with, our Products, they can receive information about what you post or share. For example, when you play a game with your Facebook friends or use a Facebook Comment or Share button on a website, the game developer or website can receive information about your activities in the game or receive a comment or link that you share from the website on Facebook. Also, when you download or use such third-party services, they can access your public profile on Facebook, and any information that you share with them. Apps and websites you use may receive your list of Facebook friends if you choose to share it with them. But apps and websites you use will not be able to receive any other information about your Facebook friends from you, or information about any of your Instagram followers (although your friends and followers may, of course, choose to share this information themselves). Information collected by these third-party services is subject to their own terms and policies, not this one.

Devices and operating systems providing native versions of Facebook and Instagram (i.e. where we have not developed our own first-party apps) will have access to all information you choose to share with them, including information your friends share with you, so they can provide our core functionality to you.

Note: We are in the process of restricting developers’ data access even further to help prevent abuse. For example, we will remove developers’ access to your Facebook and Instagram data if you haven’t used their app in 3 months, and we are changing Login, so that in the next version, we will reduce the data that an app can request without app review to include only name, Instagram username and bio, profile photo and email address. Requesting any other data will require our approval.[297]

Facebook will also share data with law enforcement.[297]

Facebook’s policies have changed repeatedly since the service’s debut, amid a series of controversies covering everything from how well it secures user data, to what extent it allows users to control access, to the kinds of access given to third parties, including businesses, political campaigns and governments. These facilities vary according to country, as some nations require the company to make data available (and limit access to services), while the European Union’s GDPR regulation mandates additional privacy protections.[301]

Bug Bounty Program

On July 29, 2011, Facebook announced its Bug Bounty Program that paid security researchers a minimum of $500 ($602.00 in 2021 dollars[30]) for reporting security holes. The company promised not to pursue «white hat» hackers who identified such problems.[302][303] This led researchers in many countries to participate, particularly in India and Russia.[304]

Reception

Userbase

Facebook’s rapid growth began as soon as it became available and continued through 2018, before beginning to decline.

Facebook passed 100 million registered users in 2008,[305] and 500 million in July 2010.[67] According to the company’s data at the July 2010 announcement, half of the site’s membership used Facebook daily, for an average of 34 minutes, while 150 million users accessed the site by mobile.[68]

In October 2012, Facebook’s monthly active users passed one billion,[94][306] with 600 million mobile users, 219 billion photo uploads, and 140 billion friend connections.[95] The 2 billion user mark was crossed in June 2017.[307][308]

In November 2015, after skepticism about the accuracy of its «monthly active users» measurement, Facebook changed its definition to a logged-in member who visits the Facebook site through the web browser or mobile app, or uses the Facebook Messenger app, in the 30-day period prior to the measurement. This excluded the use of third-party services with Facebook integration, which was previously counted.[309]

From 2017 to 2019, the percentage of the U.S. population over the age of 12 who use Facebook has declined, from 67% to 61% (a decline of some 15 million U.S. users), with a higher drop-off among younger Americans (a decrease in the percentage of U.S. 12- to 34-year-olds who are users from 58% in 2015 to 29% in 2019).[310][311] The decline coincided with an increase in the popularity of Instagram, which is also owned by Meta.[310][311]

The number of daily active users experienced a quarterly decline for the first time in the last quarter of 2021, down to 1.929 billion from 1.930 billion,[312] but increased again the next quarter despite being banned in Russia.[313]

Historically, commentators have offered predictions of Facebook’s decline or end, based on causes such as a declining user base;[314] the legal difficulties of being a closed platform, inability to generate revenue, inability to offer user privacy, inability to adapt to mobile platforms, or Facebook ending itself to present a next generation replacement;[315] or Facebook’s role in Russian interference in the 2016 United States elections.[316]

Facebook popularity. Active users (in millions) of Facebook increased from just a million

in 2004 to 2.8 billion in 2020.[301][317]

Demographics

The highest number of Facebook users as of October 2018 are from India and the United States, followed by Indonesia, Brazil and Mexico.[319] Region-wise, the highest number of users are from Asia-Pacific (947 million) followed by Europe (381 million) and US-Canada (242 million). The rest of the world has 750 million users.[320]

Over the 2008–2018 period, the percentage of users under 34 declined to less than half of the total.[301]

Censorship

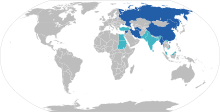

Map showing the countries that are either currently blocking or have blocked Facebook in the past

Currently blocked

Formerly blocked

In many countries the social networking sites and mobile apps have been blocked temporarily or permanently, including China,[321] Iran,[322] Vietnam,[323] Pakistan,[324] Syria,[325] and North Korea. In May 2018, the government of Papua New Guinea announced that it would ban Facebook for a month while it considered the impact of the website on the country, though no ban has since occurred.[326] In 2019, Facebook announced it would start enforcing its ban on users, including influencers, promoting any vape, tobacco products, or weapons on its platforms.[327]

Criticisms and controversies

«I’m here today because I believe Facebook’s products harm children, stoke division, and weaken our democracy. The company’s leadership knows how to make Facebook and Instagram safer, but won’t make the necessary changes because they have put their astronomical profits before people.»

—Frances Haugen, condemning lack of transparency around Facebook at a US congressional hearing (2021).[328]

«I don’t believe private companies should make all of the decisions on their own. That’s why we have advocated for updated internet regulations for several years now. I have testified in Congress multiple times and asked them to update these regulations. I’ve written op-eds outlining the areas of regulation we think are most important related to elections, harmful content, privacy, and competition.»

—Mark Zuckerberg, responding to Frances Haugen’s revelations (2021).[329]

Facebook’s importance and scale has led to criticisms in many domains. Issues include Internet privacy, excessive retention of user information,[330] its facial recognition software, DeepFace[331][332] its addictive quality[333] and its role in the workplace, including employer access to employee accounts.[334]

Facebook has been criticized for electricity usage,[335] tax avoidance,[336] real-name user requirement policies,[337] censorship[338][339] and its involvement in the United States PRISM surveillance program.[340]

According to The Express Tribune, Facebook «avoided billions of dollars in tax using offshore companies».[341]

Facebook is alleged to have harmful psychological effects on its users, including feelings of jealousy[342][343] and stress,[344][345] a lack of attention[346] and social media addiction.[347][348] According to Kaufmann et al., mothers’ motivations for using social media are often related to their social and mental health.[349] European antitrust regulator Margrethe Vestager stated that Facebook’s terms of service relating to private data were «unbalanced».[350]

Facebook has been criticized for allowing users to publish illegal or offensive material. Specifics include copyright and intellectual property infringement,[351] hate speech,[352][353] incitement of rape[354] and terrorism,[355][356] fake news,[357][358][359] and crimes, murders, and livestreaming violent incidents.[360][361][362]

Sri Lanka blocked both Facebook and WhatsApp in May 2019 after anti-Muslim riots, the worst in the country since the Easter Sunday bombing in the same year as a temporary measure to maintain peace in Sri Lanka.[363][364]

Facebook removed 3 billion fake accounts only during the last quarter of 2018 and the first quarter of 2019;[365] in comparison, the social network reports 2.39 billion monthly active users.[365]

In late July 2019, the company announced it was under antitrust investigation by the Federal Trade Commission.[366]

Privacy

Facebook has faced a steady stream of controversies over how it handles user privacy, repeatedly adjusting its privacy settings and policies.[367]

In 2010, the US National Security Agency began taking publicly posted profile information from Facebook, among other social media services.[368]

On November 29, 2011, Facebook settled Federal Trade Commission charges that it deceived consumers by failing to keep privacy promises.[369] In August 2013 High-Tech Bridge published a study showing that links included in Facebook messaging service messages were being accessed by Facebook.[370] In January 2014 two users filed a lawsuit against Facebook alleging that their privacy had been violated by this practice.[371]

On June 7, 2018, Facebook announced that a bug had resulted in about 14 million Facebook users having their default sharing setting for all new posts set to «public».[372]

On April 4, 2019, half a billion records of Facebook users were found exposed on Amazon cloud servers, containing information about users’ friends, likes, groups, and checked-in locations, as well as names, passwords and email addresses.[373]

The phone numbers of at least 200 million Facebook users were found to be exposed on an open online database in September 2019. They included 133 million US users, 18 million from the UK, and 50 million from users in Vietnam. After removing duplicates, the 419 million records have been reduced to 219 million. The database went offline after TechCrunch contacted the web host. It is thought the records were amassed using a tool that Facebook disabled in April 2018 after the Cambridge Analytica controversy. A Facebook spokeswoman said in a statement: «The dataset is old and appears to have information obtained before we made changes last year…There is no evidence that Facebook accounts were compromised.»[374]

Facebook’s privacy problems resulted in companies like Viber Media and Mozilla discontinuing advertising on Facebook’s platforms.[375][376]

Racial bias

Facebook was accused of committing «systemic» racial bias by EEOC based on the complaints of three rejected candidates and a current employee of the company. The three rejected employees along with the Operational Manager at Facebook as of March 2021 accused the firm of discriminating against Black people. The EEOC has initiated an investigation into the case.[377]

Shadow profiles

A «shadow profile» refers to the data Facebook collects about individuals without their explicit permission. For example, the «like» button that appears on third-party websites allows the company to collect information about an individual’s internet browsing habits, even if the individual is not a Facebook user.[378][379] Data can also be collected by other users. For example, a Facebook user can link their email account to their Facebook to find friends on the site, allowing the company to collect the email addresses of users and non-users alike.[380] Over time, countless data points about an individual are collected; any single data point perhaps cannot identify an individual, but together allows the company to form a unique «profile.»

This practice has been criticized by those who believe people should be able to opt-out of involuntary data collection. Additionally, while Facebook users have the ability to download and inspect the data they provide to the site, data from the user’s «shadow profile» is not included, and non-users of Facebook do not have access to this tool regardless. The company has also been unclear whether or not it is possible for a person to revoke Facebook’s access to their «shadow profile.»[378]

Cambridge Analytica

Facebook customer Global Science Research sold information on over 87 million Facebook users to Cambridge Analytica, a political data analysis firm led by Alexander Nix.[381] While approximately 270,000 people used the app, Facebook’s API permitted data collection from their friends without their knowledge.[382] At first Facebook downplayed the significance of the breach, and suggested that Cambridge Analytica no longer had access. Facebook then issued a statement expressing alarm and suspended Cambridge Analytica. Review of documents and interviews with former Facebook employees suggested that Cambridge Analytica still possessed the data.[383] This was a violation of Facebook’s consent decree with the Federal Trade Commission. This violation potentially carried a penalty of $40,000 ($43,165 in 2021 dollars[30]) per occurrence, totalling trillions of dollars.[384]

According to The Guardian, both Facebook and Cambridge Analytica threatened to sue the newspaper if it published the story. After publication, Facebook claimed that it had been «lied to». On March 23, 2018, The English High Court granted an application by the Information Commissioner’s Office for a warrant to search Cambridge Analytica’s London offices, ending a standoff between Facebook and the Information Commissioner over responsibility.[385]

On March 25, Facebook published a statement by Zuckerberg in major UK and US newspapers apologizing over a «breach of trust».[386]

You may have heard about a quiz app built by a university researcher that leaked Facebook data of millions of people in 2014. This was a breach of trust, and I’m sorry we didn’t do more at the time. We’re now taking steps to make sure this doesn’t happen again.

We’ve already stopped apps like this from getting so much information. Now we’re limiting the data apps get when you sign in using Facebook.

We’re also investigating every single app that had access to large amounts of data before we fixed this. We expect there are others. And when we find them, we will ban them and tell everyone affected.

Finally, we’ll remind you which apps you’ve given access to your information – so you can shut off the ones you don’t want anymore.

Thank you for believing in this community. I promise to do better for you.

On March 26, the Federal Trade Commission opened an investigation into the matter.[387] The controversy led Facebook to end its partnerships with data brokers who aid advertisers in targeting users.[367]

On April 24, 2019, Facebook said it could face a fine between $3 billion ($3.18 billion in 2021 dollars[30]) to $5 billion ($5.3 billion in 2021 dollars[30]) as the result of an investigation by the Federal Trade Commission. The agency has been investigating Facebook for possible privacy violations, but has not announced any findings yet.[388]

Facebook also implemented additional privacy controls and settings[389] in part to comply with the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which took effect in May.[390] Facebook also ended its active opposition to the California Consumer Privacy Act.[391]

Some, such as Meghan McCain have drawn an equivalence between the use of data by Cambridge Analytica and the Barack Obama’s 2012 campaign, which, according to Investor’s Business Daily, «encouraged supporters to download an Obama 2012 Facebook app that, when activated, let the campaign collect Facebook data both on users and their friends.»[392][393][394] Carol Davidsen, the Obama for America (OFA) former director of integration and media analytics, wrote that «Facebook was surprised we were able to suck out the whole social graph, but they didn’t stop us once they realised that was what we were doing.»[393][394] PolitiFact has rated McCain’s statements «Half-True», on the basis that «in Obama’s case, direct users knew they were handing over their data to a political campaign» whereas with Cambridge Analytica, users thought they were only taking a personality quiz for academic purposes, and while the Obama campaign only used the data «to have their supporters contact their most persuadable friends», Cambridge Analytica «targeted users, friends and lookalikes directly with digital ads.»[395]

Breaches

On September 28, 2018, Facebook experienced a major breach in its security, exposing the data of 50 million users. The data breach started in July 2017 and was discovered on September 16.[396] Facebook notified users affected by the exploit and logged them out of their accounts.[397][398]

In March 2019, Facebook confirmed a password compromise of millions of Facebook lite application users also affected millions of Instagram users. The reason cited was the storage of password as plain text instead of encryption which could be read by its employees.[399]

On December 19, 2019, security researcher Bob Diachenko discovered a database containing more than 267 million Facebook user IDs, phone numbers, and names that were left exposed on the web for anyone to access without a password or any other authentication.[400]

In February 2020, Facebook encountered a major security breach in which its official Twitter account was hacked by a Saudi Arabia-based group called «OurMine». The group has a history of actively exposing high-profile social media profiles’ vulnerabilities.[401]

In April 2021, The Guardian reported approximately half a billion users’ data had been stolen including birthdates and phone numbers. Facebook alleged it was «old data» from a problem fixed in August 2019 despite the data’s having been released a year and a half later only in 2021; it declined to speak with journalists, had apparently not notified regulators, called the problem «unfixable», and said it would not be advising users.[402]

Phone data and activity

After acquiring Onavo in 2013, Facebook used its Onavo Protect virtual private network (VPN) app to collect information on users’ web traffic and app usage. This allowed Facebook to monitor its competitors’ performance, and motivated Facebook to acquire WhatsApp in 2014.[403][404][405] Media outlets classified Onavo Protect as spyware.[406][407][408] In August 2018, Facebook removed the app in response to pressure from Apple, who asserted that it violated their guidelines.[409][410] The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission sued Facebook on December 16, 2020, for «false, misleading or deceptive conduct» in response to the company’s use of personal data obtained from Onavo for business purposes in contrast to Onavo’s privacy-oriented marketing.[411][412]

In 2016, Facebook Research launched Project Atlas, offering some users between the ages of 13 and 35 up to $20 per month ($23.00 in 2021 dollars[30]) in exchange for their personal data, including their app usage, web browsing history, web search history, location history, personal messages, photos, videos, emails and Amazon order history.[413][414] In January 2019, TechCrunch reported on the project. This led Apple to temporarily revoke Facebook’s Enterprise Developer Program certificates for one day, preventing Facebook Research from operating on iOS devices and disabling Facebook’s internal iOS apps.[414][415][416]

Ars Technica reported in April 2018 that the Facebook Android app had been harvesting user data, including phone calls and text messages, since 2015.[417][418][419] In May 2018, several Android users filed a class action lawsuit against Facebook for invading their privacy.[420][421]

In January 2020, Facebook launched the Off-Facebook Activity page, which allows users to see information collected by Facebook about their non-Facebook activities.[422] The Washington Post columnist Geoffrey A. Fowler found that this included what other apps he used on his phone, even while the Facebook app was closed, what other web sites he visited on his phone, and what in-store purchases he made from affiliated businesses, even while his phone was completely off.[423]

In November 2021, a report was published by Fairplay, Global Action Plan and Reset Australia detailing accusations that Facebook was continuing to manage their ad targeting system with data collected from teen users.[424] The accusations follow announcements by Facebook in July 2021 that they would cease ad targeting children.[425][426]

Public apologies

The company first apologized for its privacy abuses in 2009.[427]

Facebook apologies have appeared in newspapers, television, blog posts and on Facebook.[428] On March 25, 2018, leading US and UK newspapers published full-page ads with a personal apology from Zuckerberg. Zuckerberg issued a verbal apology on CNN.[429] In May 2010, he apologized for discrepancies in privacy settings.[428]

Previously, Facebook had its privacy settings spread out over 20 pages, and has now put all of its privacy settings on one page, which makes it more difficult for third-party apps to access the user’s personal information.[367] In addition to publicly apologizing, Facebook has said that it will be reviewing and auditing thousands of apps that display «suspicious activities» in an effort to ensure that this breach of privacy does not happen again.[430] In a 2010 report regarding privacy, a research project stated that not a lot of information is available regarding the consequences of what people disclose online so often what is available are just reports made available through popular media.[431] In 2017, a former Facebook executive went on the record to discuss how social media platforms have contributed to the unraveling of the «fabric of society».[432]

Content disputes and moderation

Facebook relies on its users to generate the content that bonds its users to the service. The company has come under criticism both for allowing objectionable content, including conspiracy theories and fringe discourse,[433] and for prohibiting other content that it deems inappropriate.

Misinformation and fake news

Facebook has been criticized as a vector for fake news, and has been accused of bearing responsibility for the conspiracy theory that the United States created ISIS,[434] false anti-Rohingya posts being used by Myanmar’s military to fuel genocide and ethnic cleansing,[435][436] enabling climate change denial[437][438][439] and Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting conspiracy theorists,[440] and anti-refugee attacks in Germany.[441][442][443] The government of the Philippines has also used Facebook as a tool to attack its critics.[444]

In 2017, Facebook partnered with fact checkers from the Poynter Institute’s International Fact-Checking Network to identify and mark false content, though most ads from political candidates are exempt from this program.[445][446] As of 2018, Facebook had over 40 fact-checking partners across the world, including The Weekly Standard.[447] Critics of the program have accused Facebook of not doing enough to remove false information from its website.[447][448]

Facebook has repeatedly amended its content policies. In July 2018, it stated that it would «downrank» articles that its fact-checkers determined to be false, and remove misinformation that incited violence.[449] Facebook stated that content that receives «false» ratings from its fact-checkers can be demonetized and suffer dramatically reduced distribution. Specific posts and videos that violate community standards can be removed on Facebook.[450]

In May 2019, Facebook banned a number of «dangerous» commentators from its platform, including Alex Jones, Louis Farrakhan, Milo Yiannopoulos, Paul Joseph Watson, Paul Nehlen, David Duke, and Laura Loomer, for allegedly engaging in «violence and hate».[451][452]

In May 2020, Facebook agreed to a preliminary settlement of $52 million ($54.4 million in 2021 dollars[30]) to compensate U.S.-based Facebook content moderators for their psychological trauma suffered on the job.[453][454] Other legal actions around the world, including in Ireland, await settlement.[455]

In September 2020, the Government of Thailand utilized the Computer Crime Act for the first time to take action against Facebook and Twitter for ignoring requests to take down content and not complying with court orders.[456]

Threats and incitement

Professor Ilya Somin reported that he had been the subject of death threats on Facebook in April 2018 from Cesar Sayoc, who threatened to kill Somin and his family and «feed the bodies to Florida alligators». Somin’s Facebook friends reported the comments to Facebook, which did nothing except dispatch automated messages.[457] Sayoc was later arrested for the October 2018 United States mail bombing attempts directed at Democratic politicians.

Terrorism

Force v. Facebook, Inc., 934 F.3d 53 (2nd Cir. 2019) was a case that alleged Facebook was profiting off recommendations for Hamas. In 2019 the US Second Circuit Appeals Court held that Section 230 bars civil terrorism claims against social media companies and internet service providers, the first federal appellate court to do so.

Hate speech

In October 2020, Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan urged Mark Zuckerberg, through a letter posted on government’s Twitter account, to ban Islamophobic content on Facebook, warning that it encouraged extremism and violence.[458]

In October 2020, the company announced that it would ban Holocaust denial.[459]

In October 2022, Media Matters for America published a report that Facebook and Instagram were still profiting off advertisements using the slur «groomer» for LGBT people.[460] The article reported that Meta had previously confirmed that the use of this word for the LGBT community violates its hate speech policies.[460] The story was subsequently picked up by other news outlets such as the New York Daily News, PinkNews, and LGBTQ Nation.[461][462][463]

Violent Erotica

There are ads on Facebook and Instagram containing sexually explicit content, descriptions of graphic violence and content promoting acts of self harm. Many of the ads are for webnovel apps backed by tech giants Bytedance and Tencent.[464]

InfoWars

Facebook was criticized for allowing InfoWars to publish falsehoods and conspiracy theories.[450][465][466][467][468] Facebook defended its actions in regards to InfoWars, saying «we just don’t think banning Pages for sharing conspiracy theories or false news is the right way to go.»[466] Facebook provided only six cases in which it fact-checked content on the InfoWars page over the period September 2017 to July 2018.[450] In 2018 InfoWars falsely claimed that the survivors of the Parkland shooting were «actors». Facebook pledged to remove InfoWars content making the claim, although InfoWars videos pushing the false claims were left up, even though Facebook had been contacted about the videos.[450] Facebook stated that the videos never explicitly called them actors.[450] Facebook also allowed InfoWars videos that shared the Pizzagate conspiracy theory to survive, despite specific assertions that it would purge Pizzagate content.[450] In late July 2018 Facebook suspended the personal profile of InfoWars head Alex Jones for 30 days.[469] In early August 2018, Facebook banned the four most active InfoWars-related pages for hate speech.[470]

Political manipulation

As a dominant social-web service with massive outreach, Facebook have been used by identified or unidentified political operatives to affect public opinion. Some of these activities have been done in violation of the platform policies, creating «coordinated inauthentic behavior», support or attacks. These activities can be scripted or paid. Various such abusive campaign have been revealed in recent years, best known being the Russian interference in the 2016 United States elections. In 2021, former Facebook analyst within the Spam and Fake Engagement teams, Sophie Zhang, reported more than 25 political subversion operations and criticized the general slow reaction time, oversightless, laissez-faire attitude by Facebook.[471][472][473]

Influence Operations and Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior

In 2018, Facebook stated that during 2018 they had identified «coordinated inauthentic behavior» in «many Pages, Groups and accounts created to stir up political debate, including in the US, the Middle East, Russia and the UK.»[474]

Campaigns operated by the British intelligence agency unit, called Joint Threat Research Intelligence Group, have broadly fallen into two categories; cyber attacks and propaganda efforts. The propaganda efforts utilize «mass messaging» and the «pushing [of] stories» via social media sites like Facebook.[475][476] Israel’s Jewish Internet Defense Force, China’s 50 Cent Party and Turkey’s AK Trolls also focus their attention on social media platforms like Facebook.[477][478][479][480]

In July 2018, Samantha Bradshaw, co-author of the report from the Oxford Internet Institute (OII) at Oxford University, said that «The number of countries where formally organised social media manipulation occurs has greatly increased, from 28 to 48 countries globally. The majority of growth comes from political parties who spread disinformation and junk news around election periods.»[481]

In October 2018, The Daily Telegraph reported that Facebook «banned hundreds of pages and accounts that it says were fraudulently flooding its site with partisan political content – although they came from the United States instead of being associated with Russia.»[482]

In December 2018, The Washington Post reported that «Facebook has suspended the account of Jonathon Morgan, the chief executive of a top social media research firm» New Knowledge, «after reports that he and others engaged in an operation to spread disinformation» on Facebook and Twitter during the 2017 United States Senate special election in Alabama.[483][484]

In January 2019, Facebook said it has removed 783 Iran-linked accounts, pages and groups for engaging in what it called «coordinated inauthentic behaviour».[485]

In May 2019, Tel Aviv-based private intelligence agency Archimedes Group was banned from Facebook for «coordinated inauthentic behavior» after Facebook found fake users in countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and Southeast Asia.[486] Facebook investigations revealed that Archimedes had spent some $1.1 million ($1.17 million in 2021 dollars[30]) on fake ads, paid for in Brazilian reais, Israeli shekels and US dollars.[487] Facebook gave examples of Archimedes Group political interference in Nigeria, Senegal, Togo, Angola, Niger and Tunisia.[488] The Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab said in a report that «The tactics employed by Archimedes Group, a private company, closely resemble the types of information warfare tactics often used by governments, and the Kremlin in particular.»[489][490]

On May 23, 2019, Facebook released its Community Standards Enforcement Report highlighting that it has identified several fake accounts through artificial intelligence and human monitoring. In a period of six months, October 2018-March 2019, the social media website removed a total of 3.39 billion fake accounts. The number of fake accounts was reported to be more than 2.4 billion real people on the platform.[491]

In July 2019, Facebook advanced its measures to counter deceptive political propaganda and other abuse of its services. The company removed more than 1,800 accounts and pages that were being operated from Russia, Thailand, Ukraine and Honduras.[492] After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, it was announced that the internet regulatory committee would block access to Facebook.[493]

On October 30, 2019, Facebook deleted several accounts of the employees working at the Israeli NSO Group, stating that the accounts were «deleted for not following our terms». The deletions came after WhatsApp sued the Israeli surveillance firm for targeting 1,400 devices with spyware.[494]

In 2020, Facebook helped found American Edge, an anti-regulation lobbying firm to fight anti-trust probes.[495]

The Thailand government is forcing Facebook to take down a Facebook group called Royalist Marketplace with 1 million members following potentially illegal posts shared. The authorities have also threatened Facebook with legal action. In response, Facebook is planning to take legal action against the Thai government for suppression of freedom of expression and violation of human rights.[496]