Антитрестовый закон Шермана, принятый в США в начале 20 века, буквально объявил войну монополиям и крупным компаниям. В теории он имел весьма многообещающее будущее, на практике же оказался малоэффективным. В чем заключалась его суть и каковы причины неудачи его применения, читайте в статье.

Начало XX века в США: роль государства в экономике и социальных отношениях

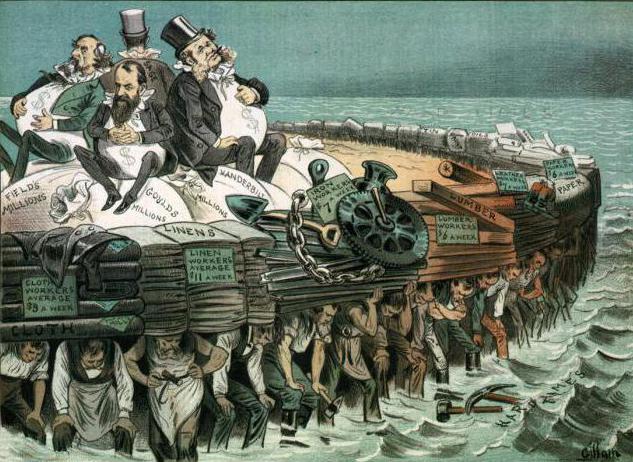

Америка в конце 19 в. — начале 20 в. бешеными темпами трансформировалась в страну классического корпоративного капитализма. В ней без каких-либо ограничений функционировали монополии, гигантские тресты. Вполне логично, что они жестко ограничивали свободу рыночной конкуренции и диктовали малому и среднему бизнесу такие условия, которые приводили к его разорению. Конкуренции они не выдерживали. Чего стоит гигант, принадлежащий Джону Рокфеллеру под названием Standart Oil, который к началу 20 века захватил рынок нефтепродуктов США на 95%! Первым актом, принятым с целью защиты торговли и коммерции от монополии и ограничений, стал закон Шермана. Однако, вопреки ожиданиям, он не стал так называемой в народе «хартией промышленной свободы».

Кто такой Шерман?

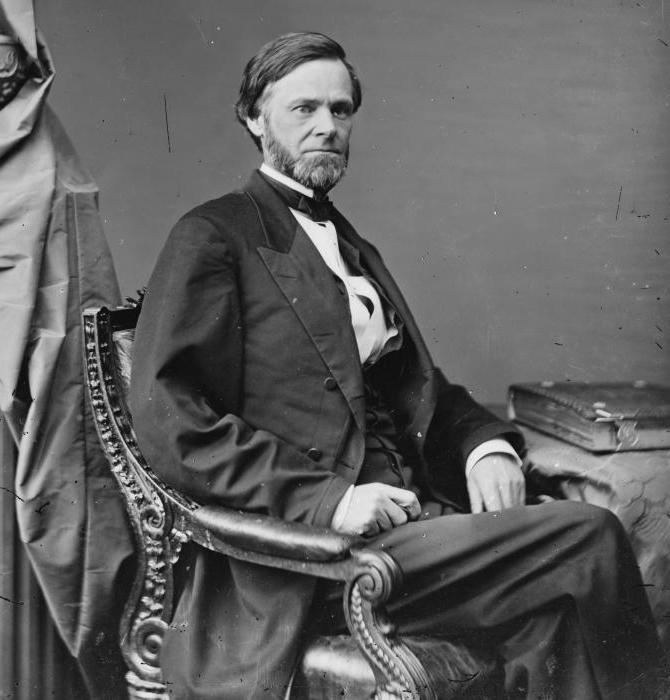

Инициатором упомянутого выше законопроекта был известный американский политик Джон Шерман, имя которого акт впоследствии и получил. Будущий член Палаты представителей и сенатор штата Огайо, а также 35-й государственный секретарь и министр финансов США родился 7 марта 1897 года в городе Ланкастер. Его отец работал судьей, а семья была довольно велика и состояла из родителей и 11 детей. Образование Шерман получил в обычной школе, затем он заинтересовался правом и, пройдя обучение, был принят в коллегию адвокатов.

После женитьбы его привлекла политика. В 1854 году в возрасте 43 лет его избрали в Палату представителей родного штата Огайо. В 1980 году он предпринял попытку занять пост президента страны, но уступил Д. Гарфилду. Его личность является весьма значимой в истории страны, однако остальному миру наиболее знаком Закон Шермана, принятый в США. Относится к сфере трудового права он косвенно и между тем стал предпосылкой для положительных изменений в данной области законодательства.

Суть закона

Акт Шермана стал первым антимонополистическим законом Америки. Названный по имени своего инициатора, он был одобрен сенатом страны в апреле 1890 г. (51 голос против одного), палатой представителей (единогласно) и утвержден президентом Гарриссоном. В силу закон вступил 2 июля 1890 года.

Текст его провозглашал, что препятствование свободной торговле путем создания трестов (монополий), а также вступление с этими целями в сговор есть не что иное, как преступление. Следует отметить, что закон Шермана в течение десятилетия находился в «спящем» режиме, пока к нему не обратился двадцать шестой президент США Теодор Рузвельт.

Акт не был направлен против трестов и монополий как таковых. Однако он касался прямых и явных ограничений свободной торговли не только в национальном масштабе (между отдельными штатами), но и в международном. Д. Рокфеллер и его компания стали главной мишенью. Так, в 1904 году против Standart Oil был подан ряд антимонопольных исков. Верховный суд принял решение о разделении компании. Д. Рокфеллер, раздробив Standart Oil на 34 дочерние фирмы, между тем, сохранил над ними контроль.

В чем ошибка?

Закон Шермана, принятый в США, относится к сфере экономики и отчасти социальной политики – областей, которые на тот момент требовали обновления. Эффект от него был довольно ограниченным. Более того, акт очень часто применялся не по прямому назначению. Произвольное толкование закона судебными органами привело к тому, что профсоюзы работников были приравнены к монополиям, а забастовки – к сговорам, имеющим целью ограничение свободной торговли. В действительности акт, принятый для народа, в конечном итоге обратился против него. Данная лазейка в законе была устранена только в 1914 году при помощи Акта Клейтона. Примечательно, что Закон Шермана в определенной части действует и в наше время, он включен в Федеральный Кодекс США.

Что последовало далее?

Долгожданный и первый антимонопольный закон не принес желаемых результатов. Социальное расслоение в обществе продолжало усугубляться, рядовые американские граждане оказались в весьма бедственном положении, присутствовали все признаки экономической депрессии. Все это естественно привело к росту недовольства возрастающим корпоративным капиталом среди самых разнообразных слоев населения: прогрессивной интеллигенции, фермеров, рабочих. Страна погружается в антитрестовское движение, сопровождающееся ростом активности профсоюзов и борьбой беднейшего класса за систему государственной защиты. Постепенно требования об «обновлении» социальной и экономической политики охватили партийные верхушки не только демократов, но и республиканцев. Первым шагом на пути к решению проблемы стал «Акт об ускорении судебного разбирательства и разрешения процессов по справедливости» (1903 г.), следом был принят закон о создании Министерства торговли и труда.

Оказавшись малоэффективным на практике, все же предпосылкой к положительным сдвигам стал именно закон Шермана, принятый в США. Относится к сфере какого права данный нормативный акт, каково его содержание, где крылась одна из главных ошибок – ответы на эти вопросы отражены в статье. Полный текст документа доступен как на языке оригинала, так и в переводе. Он будет особенно актуален для тех, кто интересуется новой и новейшей историей США.

|

|

| Long title | An Act to Protect Trade and Commerce Against Unlawful Restraints and Monopolies |

|---|---|

| Enacted by | the 51st United States Congress |

| Citations | |

| Statutes at Large | 26 Stat. 209 |

| Legislative history | |

|

|

| United States Supreme Court cases | |

|

List

|

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890[1] (26 Stat. 209, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1–7) is a United States antitrust law which prescribes the rule of free competition among those engaged in commerce. It was passed by Congress and is named for Senator John Sherman, its principal author.

The Sherman Act broadly prohibits 1) anticompetitive agreements and 2) unilateral conduct that monopolizes or attempts to monopolize the relevant market. The Act authorizes the Department of Justice to bring suits to enjoin (i.e. prohibit) conduct violating the Act, and additionally authorizes private parties injured by conduct violating the Act to bring suits for treble damages (i.e. three times as much money in damages as the violation cost them). Over time, the federal courts have developed a body of law under the Sherman Act making certain types of anticompetitive conduct per se illegal, and subjecting other types of conduct to case-by-case analysis regarding whether the conduct unreasonably restrains trade.

The law attempts to prevent the artificial raising of prices by restriction of trade or supply.[2] «Innocent monopoly», or monopoly achieved solely by merit, is legal, but acts by a monopolist to artificially preserve that status, or nefarious dealings to create a monopoly, are not. The purpose of the Sherman Act is not to protect competitors from harm from legitimately successful businesses, nor to prevent businesses from gaining honest profits from consumers, but rather to preserve a competitive marketplace to protect consumers from abuses.[3]

Background[edit]

In Spectrum Sports, Inc. v. McQuillan 506 U.S. 447 (1993) the Supreme Court said:

The purpose of the [Sherman] Act is not to protect businesses from the working of the market; it is to protect the public from the failure of the market. The law directs itself not against conduct which is competitive, even severely so, but against conduct which unfairly tends to destroy competition itself.[4]

According to its authors, it was not intended to impact market gains obtained by honest means, by benefiting the consumers more than the competitors. Senator George Hoar of Massachusetts, another author of the Sherman Act, said the following:

… [a person] who merely by superior skill and intelligence…got the whole business because nobody could do it as well as he could was not a monopolist…(but was if) it involved something like the use of means which made it impossible for other persons to engage in fair competition.»[5]

At Apex Hosiery Co. v. Leader 310 U.S. 469, 310 U. S. 492-93 and n. 15:

The legislative history of the Sherman Act, as well as the decisions of this Court interpreting it, show that it was not aimed at policing interstate transportation or movement of goods and property. The legislative history and the voluminous literature which was generated in the course of the enactment and during fifty years of litigation of the Sherman Act give no hint that such was its purpose.[6] They do not suggest that, in general, state laws or law enforcement machinery were inadequate to prevent local obstructions or interferences with interstate transportation, or presented any problem requiring the interposition of federal authority.[7] In 1890, when the Sherman Act was adopted, there were only a few federal statutes imposing penalties for obstructing or misusing interstate transportation.[8] With an expanding commerce, many others have since been enacted safeguarding transportation in interstate commerce as the need was seen, including statutes declaring conspiracies to interfere or actual interference with interstate commerce by violence or threats of violence to be felonies.[9] The law was enacted in the era of «trusts» and of «combinations» of businesses and of capital organized and directed to control of the market by suppression of competition in the marketing of goods and services, the monopolistic tendency of which had become a matter of public concern. The goal was to prevent restraints of free competition in business and commercial transactions which tended to restrict production, raise prices, or otherwise control the market to the detriment of purchasers or consumers of goods and services, all of which had come to be regarded as a special form of public injury.[10] For that reason the phrase «restraint of trade,» which, as will presently appear, had a well understood meaning in common law, was made the means of defining the activities prohibited. The addition of the words «or commerce among the several States» was not an additional kind of restraint to be prohibited by the Sherman Act, but was the means used to relate the prohibited restraint of trade to interstate commerce for constitutional purposes, Atlantic Cleaners & Dyers v. United States, 286 U. S. 427, 286 U. S. 434, so that Congress, through its commerce power, might suppress and penalize restraints on the competitive system which involved or affected interstate commerce. Because many forms of restraint upon commercial competition extended across state lines so as to make regulation by state action difficult or impossible, Congress enacted the Sherman Act, 21 Cong.Rec. 2456. It was in this sense of preventing restraints on commercial competition that Congress exercised «all the power it possessed.» Atlantic Cleaners & Dyers v. United States, supra, 286 U. S. 435.

At Addyston Pipe and Steel Company v. United States, 85 F.2d 1, affirmed, 175 U. S. 175 U.S. 211;

At Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States, 221 U. S. 1, 221 U. S. 54-58.

Provisions[edit]

Original text[edit]

The Sherman Act is divided into three sections. Section 1 delineates and prohibits specific means of anticompetitive conduct, while Section 2 deals with end results that are anti-competitive in nature. Thus, these sections supplement each other in an effort to prevent businesses from violating the spirit of the Act, while technically remaining within the letter of the law. Section 3 simply extends the provisions of Section 1 to U.S. territories and the District of Columbia.

Section 1:

- Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, is declared to be illegal.[11]

Section 2:

- Every person who shall monopolize, or attempt to monopolize, or combine or conspire with any other person or persons, to monopolize any part of the trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, shall be deemed guilty of a felony [. . . ][12]

Subsequent legislation expanding its scope[edit]

The Clayton Antitrust Act, passed in 1914, proscribes certain additional activities that had been discovered to fall outside the scope of the Sherman Antitrust Act. For example, the Clayton Act added certain practices to the list of impermissible activities:

- price discrimination between different purchasers, if such discrimination tends to create a monopoly

- exclusive dealing agreements

- tying arrangements

- mergers and acquisitions that substantially reduce market competition.

The Robinson–Patman Act of 1936 amended the Clayton Act. The amendment proscribed certain anti-competitive practices in which manufacturers engaged in price discrimination against equally-situated distributors.

Legacy[edit]

The federal government began filing cases under the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890. Some cases were successful and others were not; many took several years to decide, including appeals.

Notable cases filed under the act include:[13]

- United States v. Workingmen’s Amalgamated Council of New Orleans (1893), which was the first to hold that the law applied to labor unions.

- Chesapeake & Ohio Fuel Co. v. United States (1902), in which the trust was dissolved[14]

- Northern Securities Co. v. United States (1904), which reached the Supreme Court, dissolved the company and set many precedents for interpretation.

- Hale v. Henkel (1906) also reached the Supreme Court. Precedent was set for the production of documents by an officer of a company, and the self-incrimination of the officer in his or her testimony to the grand jury. Hale was an officer of the American Tobacco Co.

- Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States (1911), which broke up the company based on geography, and contributed to the Panic of 1910–11.

- United States v. American Tobacco Co. (1911), which split the company into four.

- United States v. General Electric Co (1911), where GE was judged to have violated the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, along with International General Electric, Philips, Sylvania, Tungsol, and Consolidated and Chicago Miniature. Corning and Westinghouse made consent decrees.[15]

- United States v. Motion Picture Patents Co. (1917), which ruled that the company was abusing its monopolic rights, and therefore, violated the Sherman act.

- Federal Baseball Club v. National League (1922) in which the Supreme Court ruled that Major League Baseball was not interstate commerce and was not subject to the antitrust law.

- United States v. National City Lines (1953), related to the General Motors streetcar conspiracy.

- United States v. AT&T Co., which was settled in 1982 and resulted in the breakup of the company.

- Wilk v. American Medical Association (1990) Judge Getzendanner issued her opinion that the AMA had violated Section 1, but not 2, of the Sherman Act, and that it had engaged in an unlawful conspiracy in restraint of trade «to contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession.»

- United States v. Microsoft Corp. was settled in 2001 without the breakup of the company.

Legal application[edit]

Constitutional basis for legislation[edit]

Congress claimed power to pass the Sherman Act through its constitutional authority to regulate interstate commerce. Therefore, federal courts only have jurisdiction to apply the Act to conduct that restrains or substantially affects either interstate commerce or trade within the District of Columbia. This requires that the plaintiff must show that the conduct occurred during the flow of interstate commerce or had an appreciable effect on some activity that occurs during interstate commerce.

Elements[edit]

A Section 1 violation has three elements:[16]

- (1) an agreement;

- (2) which unreasonably restrains competition; and

- (3) which affects interstate commerce.

A Section 2 monopolization violation has two elements:[17]

- (1) the possession of monopoly power in the relevant market; and

- (2) the willful acquisition or maintenance of that power as distinguished from growth or development as a consequence of a superior product, business acumen, or historic accident.

Section 2 also bans attempted monopolization, which has the following elements:

- (1) qualifying exclusionary or anticompetitive acts designed to establish a monopoly

- (2) specific intent to monopolize; and

- (3) dangerous probability of success (actual monopolization).

Violations «per se» and violations of the «rule of reason»[edit]

Violations of the Sherman Act fall (loosely[18]) into two categories:

- Violations «per se»: these are violations that meet the strict characterization of Section 1 («agreements, conspiracies or trusts in restraint of trade»). A per se violation requires no further inquiry into the practice’s actual effect on the market or the intentions of those individuals who engaged in the practice. Conduct characterized as per se unlawful is that which has been found to have a «‘pernicious effect on competition’ or ‘lack[s] . . . any redeeming virtue'»[19] Such conduct «would always or almost always tend to restrict competition and decrease output.»[20] When a per se rule is applied, a civil violation of the antitrust laws is found merely by proving that the conduct occurred and that it fell within a per se category.[21] (This must be contrasted with rule of reason analysis.) Conduct considered per se unlawful includes horizontal price-fixing,[22] horizontal market division,[23] and concerted refusals to deal.[24]

- Violations of the «rule of reason»: A totality of the circumstances test, asking whether the challenged practice promotes or suppresses market competition. Unlike with per se violations, intent and motive are relevant when predicting future consequences. The rule of reason is said to be the «traditional framework of analysis» to determine whether Section 1 is violated.[25] The court analyzes «facts peculiar to the business, the history of the restraining, and the reasons why it was imposed,»[26] to determine the effect on competition in the relevant product market.[27] A restraint violates Section 1 if it unreasonably restrains trade.[28]

-

- Quick-look: A «quick look» analysis under the rule of reason may be used when «an observer with even a rudimentary understanding of economics could conclude that the arrangements in question would have an anticompetitive effect on customers and markets,» yet the violation is also not one considered illegal per se.[29] Taking a «quick look,» economic harm is presumed from the questionable nature of the conduct, and the burden is shifted to the defendant to prove harmlessness or justification. The quick-look became a popular way of disposing of cases where the conduct was in a grey area between illegality «per se» and demonstrable harmfulness under the «rule of reason».

Modern trends[edit]

Inference of conspiracy[edit]

A modern trend has increased difficulty for antitrust plaintiffs as courts have come to hold plaintiffs to increasing burdens of pleading. Under older Section 1 precedent, it was not settled how much evidence was required to show a conspiracy. For example, a conspiracy could be inferred based on parallel conduct, etc. That is, plaintiffs were only required to show that a conspiracy was conceivable. Since the 1970s, however, courts have held plaintiffs to higher standards, giving antitrust defendants an opportunity to resolve cases in their favor before significant discovery under FRCP 12(b)(6). That is, to overcome a motion to dismiss, plaintiffs, under Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly, must plead facts consistent with FRCP 8(a) sufficient to show that a conspiracy is plausible (and not merely conceivable or possible). This protects defendants from bearing the costs of antitrust «fishing expeditions»; however it deprives plaintiffs of perhaps their only tool to acquire evidence (discovery).

Manipulation of market[edit]

Second, courts have employed more sophisticated and principled definitions of markets. Market definition is necessary, in rule of reason cases, for the plaintiff to prove a conspiracy is harmful. It is also necessary for the plaintiff to establish the market relationship between conspirators to prove their conduct is within the per se rule.

In early cases, it was easier for plaintiffs to show market relationship, or dominance, by tailoring market definition, even if it ignored fundamental principles of economics. In U.S. v. Grinnell, 384 U.S. 563 (1966), the trial judge, Charles Wyzanski, composed the market only of alarm companies with services in every state, tailoring out any local competitors; the defendant stood alone in this market, but had the court added up the entire national market, it would have had a much smaller share of the national market for alarm services that the court purportedly used. The appellate courts affirmed this finding; however, today, an appellate court would likely find this definition to be flawed. Modern courts use a more sophisticated market definition that does not permit as manipulative a definition.[citation needed]

Monopoly[edit]

Section 2 of the Act forbade monopoly. In Section 2 cases, the court has, again on its own initiative, drawn a distinction between coercive and innocent monopoly. The act is not meant to punish businesses that come to dominate their market passively or on their own merit, only those that intentionally dominate the market through misconduct, which generally consists of conspiratorial conduct of the kind forbidden by Section 1 of the Sherman Act, or Section 3 of the Clayton Act.

Application of the act outside pure commerce[edit]

While the Act was aimed at regulating businesses, its prohibition of contracts restricting commerce was applied to the activities of labor unions until the 1930s.[30] This is because unions were characterized as cartels as well (cartels of laborers).[31] In 1914 the Clayton Act created exceptions for certain union activities, but the Supreme Court ruled in Duplex Printing Press Co. v. Deering that the actions allowed by the Act were already legal. Congress included provisions in the Norris–La Guardia Act in 1932 to more explicitly exempt organized labor from antitrust enforcement, and the Supreme Court upheld these exemptions in United States v. Hutcheson 312 U.S. 219.[30]

Preemption by Section 1 of state statutes that restrain competition[edit]

To determine whether the Act preempts a state law, courts will engage in a two-step analysis, as set forth by the Supreme Court in Rice v. Norman Williams Co.

- First, they will inquire whether the state legislation «mandates or authorizes conduct that necessarily constitutes a violation of the antitrust laws in all cases, or … places irresistible pressure on a private party to violate the antitrust laws in order to comply with the statute.» Rice v. Norman Williams Co., 458 U.S. 654, 661; see also 324 Liquor Corp. v. Duffy, 479 U.S. 335 (1987) («Our decisions reflect the principle that the federal antitrust laws pre-empt state laws authorizing or compelling private parties to engage in anticompetitive behavior.»)

- Second, they will consider whether the state statute is saved from preemption by the state action immunity doctrine (aka Parker immunity). In California Retail Liquor Dealers Ass’n v. Midcal Aluminum, Inc., 445 U.S. 97, 105 (1980), the Supreme Court established a two-part test for applying the doctrine: «First, the challenged restraint must be one clearly articulated and affirmatively expressed as state policy; second, the policy must be actively supervised by the State itself.» Id. (citation and quotation marks omitted).

The antitrust laws allow coincident state regulation of competition.[32] The Supreme Court enunciated the test for determining when a state statute is in irreconcilable conflict with Section 1 of the Sherman Act in Rice v. Norman Williams Co. Different standards apply depending on whether a statute is attacked on its face or for its effects.

- A statute can be condemned on its face only when it mandates, authorizes or places irresistible pressure on private parties to engage in conduct constituting a per se violation of Section 1.[33]

- If the statute does not mandate conduct violating a per se rule, the conduct is analyzed under the rule of reason, which requires an examination of the conduct’s actual effects on competition.[34] If unreasonable anticompetitive effects are created, the required conduct violates Section 1[35] and the statute is in irreconcilable conflict with the Sherman Act.[36] Then statutory arrangement is analyzed to determine whether it qualifies as «state action» and is thereby saved from preemption.[37]

Rice sets out guidelines to aid in preemption analysis. Preemption should not occur «simply because in a hypothetical situation a private party’s compliance with the statute might cause him to violate the antitrust laws.»[38] This language suggests that preemption occurs only if economic analysis determines that the statutory requirements create «an unacceptable and unnecessary risk of anticompetitive effect,»[39] and does not occur simply because it is possible to use the statute in an anticompetitive manner.[40] It should not mean that preemption is impossible whenever both procompetitive and anticompetitive results are conceivable.[41] The per se rule «reflects the judgment that such cases are not sufficiently common or important to justify the time and expense necessary to identify them.»

Another important, yet, in the context of Rice, ambiguous guideline regarding preemption by Section 1 is the Court’s statement that a «state statute is not preempted by the federal antitrust laws simply because the state scheme might have an anticompetitive effect.»[42] The meaning of this statement is clarified by examining the three cases cited in Rice to support the statement.[43]

- In New Motor Vehicle Board v. Orrin W. Fox Co., automobile manufacturers and retail franchisees contended that the Sherman Act preempted a statute requiring manufacturers to secure the permission of a state board before opening a new dealership if and only if a competing dealer protested. They argued that a conflict existed because the statute permitted «auto dealers to invoke state power for the purpose of restraining intrabrand competition.»

- In Exxon Corp. v. Governor of Maryland, oil companies challenged a state statute requiring uniform statewide gasoline prices in situations where the Robinson-Patman Act would permit charging different prices. They reasoned that the Robinson-Patman Act is a qualification of our «more basic national policy favoring free competition» and that any state statute altering «the competitive balance that Congress struck between the Robinson-Patman and Sherman Acts» should be preempted.

- In both New Motor Vehicle and Exxon, the Court upheld the statutes and rejected the arguments presented as

-

- Merely another way of stating that the . . . statute will have an anticompetitive effect. In this sense, there is a conflict between the statute and the central policy of the Sherman Act – ‘our charter of economic liberty’. . . . Nevertheless, this sort of conflict cannot itself constitute a sufficient reason for invalidating the . . . statute. For if an adverse effect on competition were, in and of itself, enough to render a state statute invalid, the States’ power to engage in economic regulation would be effectively destroyed.[44]

- This indicates that not every anticompetitive effect warrants preemption. In neither Exxon nor New Motor Vehicle did the created effect constitute an antitrust violation. The Rice guideline therefore indicates that only when the effect unreasonably restrains trade, and is therefore a violation, can preemption occur.

- The third case cited to support the «anticompetitive effect» guideline is Joseph E. Seagram & Sons v. Hostetter, in which the Court rejected a facial Sherman Act preemption challenge to a statute requiring that persons selling liquor to wholesalers affirm that the price charged was no higher than the lowest price at which sales were made anywhere in the United States during the previous month. Since the attack was a facial one, and the state law required no per se violations, no preemption could occur. The Court also rejected the possibility of preemption due to Sherman Act violations stemming from misuse of the statute. The Court stated that rather than imposing «irresistible economic pressure» on sellers to violate the Sherman Act, the statute «appears firmly anchored to the assumption that the Sherman Act will deter any attempts by the appellants to preserve their . . . price level [in one state] by conspiring to raise the prices at which liquor is sold elsewhere in the country.» Thus, Seagram indicates that when conduct required by a state statute combines with other conduct that, taken together, constitutes an illegal restraint of trade, liability may be imposed for the restraint without requiring preemption of the state statute.

Rice v. Norman Williams Co. supports this misuse limitation on preemption. Rice states that while particular conduct or arrangements by private parties would be subject to per se or rule of reason analysis to determine liability, «[t]here is no basis . . . for condemning the statute itself by force of the Sherman Act.»[45]

Thus, when a state requires conduct analyzed under the rule of reason, a court must carefully distinguish rule of reason analysis for preemption purposes from the analysis for liability purposes. To analyze whether preemption occurs, the court must determine whether the inevitable effects of a statutory restraint unreasonably restrain trade. If they do, preemption is warranted unless the statute passes the appropriate state action tests. But, when the statutory conduct combines with other practices in a larger conspiracy to restrain trade, or when the statute is used to violate the antitrust laws in a market in which such a use is not compelled by the state statute, the private party might be subjected to antitrust liability without preemption of the statute.[citation needed]

Evidence from legislative history[edit]

The Act was not intended to regulate existing state statutes regulating commerce within state borders. The House committee, in reporting the bill which was adopted without change, declared:

No attempt is made to invade the legislative authority of the several States or even to occupy doubtful grounds. No system of laws can be devised by Congress alone which would effectually protect the people of the [322 U.S. 533, 575] United States against the evils and oppression of trusts and monopolies. Congress has no authority to deal, generally, with the subject within the States, and the States have no authority to legislate in respect of commerce between the several States or with foreign nations.[46]

See also the statement on the floor of the House by Mr. Culberson, in charge of the bill,

There is no attempt to exercise any doubtful authority on this subject, but the bill is confined strictly and alone to subjects over which, confessedly, there is no question about the legislative power of Congress. …[47]

And see the statement of Senator Edmunds, chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee which reported out the bill in the form in which it passed, that in drafting that bill the committee thought that «we would frame a bill that should be clearly within our constitutional power, that we would make its definition out of terms that were well known to the law already, and would leave it to the courts in the first instance to say how far they could carry it or its particular definitions as applicable to each particular case as the occasion might arise.»[48]

Similarly Senator Hoar, a member of that committee who with Senator Edmunds was in charge of the bill, stated

Now we are dealing with an offense against interstate or international commerce, which the State cannot regulate by penal enactment, and we find the United States without any common law. The great thing that this bill does, except affording a remedy, is to extend the common-law principles, which protected fair competition in trade in old times in England, to international and interstate commerce in the United States.[49]

Criticism[edit]

Alan Greenspan, in his essay entitled Antitrust[50] described the Sherman Act as stifling innovation and harming society. «No one will ever know what new products, processes, machines, and cost-saving mergers failed to come into existence, killed by the Sherman Act before they were born. No one can ever compute the price that all of us have paid for that Act which, by inducing less effective use of capital, has kept our standard of living lower than would otherwise have been possible.» Greenspan summarized the nature of antitrust law as: «a jumble of economic irrationality and ignorance.»[51] Greenspan at that time was a disciple and friend of Ayn Rand, and he first published Antitrust in Rand’s monthly publication The Objectivist Newsletter. Rand, who described herself as «a radical for capitalism»,[52] opposed antitrust law not only on economic grounds but also morally, as a violation of property rights, asserting that the «meaning and purpose» of antitrust law is «the penalizing of ability for being ability, the penalizing of success for being success, and the sacrifice of productive genius to the demands of envious mediocrity.»[53]

In 1890, Representative William E. Mason said «trusts have made products cheaper, have reduced prices; but if the price of oil, for instance, were reduced to one cent a barrel, it would not right the wrong done to people of this country by the trusts which have destroyed legitimate competition and driven honest men from legitimate business enterprise.»[54] Consequently, if the primary goal of the act is to protect consumers, and consumers are protected by lower prices, the act may be harmful if it reduces economy of scale, a price-lowering mechanism, by breaking up big businesses. Mason put small business survival, a justice interest, on a level concomitant with the pure economic rationale of consumer interest.[citation needed]

Economist Thomas DiLorenzo notes that Senator Sherman sponsored the 1890 William McKinley tariff just three months after the Sherman Act, and agrees with The New York Times which wrote on October 1, 1890: «That so-called Anti-Trust law was passed to deceive the people and to clear the way for the enactment of this Pro-Trust law relating to the tariff.» The Times went on to assert that Sherman merely supported this «humbug» of a law «in order that party organs might say…’Behold! We have attacked the trusts. The Republican Party is the enemy of all such rings.'»[55] Dilorenzo writes: «Protectionists did not want prices paid by consumers to fall. But they also understood that to gain political support for high tariffs they would have to assure the public that industries would not combine to increase prices to politically prohibitive levels. Support for both an antitrust law and tariff hikes would maintain high prices while avoiding the more obvious bilking of consumers.»[56]

Robert Bork was well known for his outspoken criticism of the antitrust regime. Another conservative legal scholar and judge, Richard Posner of the Seventh Circuit, does not condemn the entire regime, but expresses concern with the potential that it could be applied to create inefficiency, rather than to avoid inefficiency.[57] Posner further believes, along with a number of others, including Bork, that genuinely inefficient cartels and coercive monopolies, the target of the act, would be self-corrected by market forces, making the strict penalties of antitrust legislation unnecessary.[57] Conversely, liberal U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas criticized the judiciary for interpreting and enforcing the antitrust law unequally: «From the beginning it [the Sherman Act] has been applied by judges hostile to its purposes, friendly to the empire builders who wanted it emasculated… trusts that were dissolved reintegrated in new forms… It is ironic that the Sherman Act was truly effective in only one respect, and that was when it was applied to labor unions. Then the courts read it with a literalness that never appeared in their other decisions.»[58]

According to a 2018 study in the journal Public Choice, «Senator John Sherman of Ohio was motivated to introduce an antitrust bill in late 1889 partly as a way of enacting revenge on his political rival, General and former Governor Russell Alger of Michigan, because Sherman believed that Alger personally had cost him the presidential nomination at the 1888 Republican national convention… Sherman was able to pursue his revenge motive by combining it with the broader Republican goals of preserving high tariffs and attacking the trusts.»[59]

See also[edit]

- Alcoa

- American Bar Association

- American Tobacco Company

- Antitrust

- Bell System divestiture

- Cartel

- Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914

- DRAM price fixing

- George H. Earle, Jr.

- Plan of Bill Proposed by Hon. George H. Earle, Jr., Philadelphia. (1911) at Wikisource

- Federal Baseball Club v. National League

- Laissez-faire

- Lysine price-fixing conspiracy

- Monsanto Co. v. Spray-Rite Service Corp.

- National Linseed Oil Trust

- Northern Securities Company

- Price fixing

- Resale price maintenance

- Sarbanes–Oxley Act

- Standard Oil

- Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States

- Ticketmaster

- Tying (commerce)

- United States v. Microsoft

Notes and references[edit]

- ^ Officially re-designated as the «Sherman Act» by Congress in the Hart–Scott–Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act of 1976, (Public Law 94-435, Title 3, Sec. 305(a), 90 Stat. 1383 at p. 1397).

- ^ «Sherman AntiTrust Act, and Analysis». March 12, 2011. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011.

- ^ «This focus of U.S. competition law, on protection of competition rather than competitors, is not necessarily the only possible focus or purpose of competition law. For example, it has also been said that competition law in the European Union (EU) tends to protect the competitors in the marketplace, even at the expense of market efficiencies and consumers.»< Cseres, Katalin Judit (2005). Competition law and consumer protection. Kluwer Law International. pp. 291–293. ISBN 9789041123800. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- ^ Spectrum Sports, Inc. v. McQuillan, 506 U.S. 447, 458 (1993).

- ^ Congress, United States; Finch, James Arthur (March 26, 2018). «Bills and Debates in Congress Relating to Trusts: Fiftieth Congress to Fifty-seventh Congress, First Session, Inclusive». U.S. Government Printing Office. Archived from the original on April 9, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Footnote 11 appears here: «See the Bibliography on Trusts (1913) prepared by the Library of Congress. Cf. Homan, Industrial Combination as Surveyed in Recent Literature, 44 Quart.J.Econ., 345 (1930). With few exceptions, the articles, scientific and popular, reflected the popular idea that the Act was aimed at the prevention of monopolistic practices and restraints upon trade injurious to purchasers and consumers of goods and services by preservation of business competition. See, e.g., Seager and Gulick, Trust and Corporation Problems (1929), 367 et seq., 42 Ann.Am.Acad., Industrial Competition and Combination (July 1912); P. L. Anderson, Combination v. Competition, 4 Edit.Rev. 500 (1911); Gilbert Holland Montague, Trust Regulation Today, 105 Atl.Monthly, 1 (1910); Federal Regulation of Industry, 32 Ann.Am.Acad. of Pol.Sci., No. 108 (1908), passim; Clark, Federal Trust Policy (1931), Ch. II, V; Homan, Trusts, 15 Ency.Soc.Sciences 111, 113:

«clearly the law was inspired by the predatory competitive tactics of the great trusts, and its primary purpose was the maintenance of the competitive system in industry.»

See also Shulman, Labor and the Anti-Trust Laws, 34 Ill.L.Rev. 769; Boudin, the Sherman Law and Labor Disputes, 39 Col.L.Rev. 1283; 40 Col.L.Rev. 14.»

- ^ Footnote 12 appears here: «There was no lack of existing law to protect against evils ascribed to organized labor. Legislative and judicial action of both a criminal and civil nature already restrained concerted action by labor. See, e.g., the kinds of strikes which were declared illegal in Pennsylvania, including a strike accompanied by force or threat of harm to persons or property, Brightly’s Purdon’s Digest of 1885, pp. 426, 1172.

For collection of state statutes on labor activities, see Report of the Commissioner of Labor, Labor Laws of the Various States (1892); Bull. 370, Labor Laws of the United States with Decisions Relating Thereto, United States Bureau of Labor Statistics (1925); Witte, The Government in Labor Disputes (1932), 12–45, 61–81.»

- ^ Footnote 13 appears here: «Three statutes covered in 1890 the Congressional action in relation to obstructions to interstate commerce. A penalty was imposed for the refusal to transmit a telegraph message (R.S. § 5269, 17 Stat. 366 (1872)) for transporting nitroglycerine and other explosives without proper safeguards (R.S. § 5353, 14 Stat. 81 (1866)) and for combining to prevent the continuous carriage of freight, 24 Stat. 382, 49 U.S.C. § 7.»

- ^ Footnote 14 appears here:

«See, e.g. regulation of; interstate carriage of lottery tickets, 28 Stat. 963 (1895), 18 U.S.C. § 387; Transportation of obscene books, 29 Stat. 512 (1897), 18 U.S.C. § 396; transportation of illegally killed game, 31 Stat. 188 (1900), 18 U.S.C. §§ 392–395; interstate shipment of intoxicating liquors, 35 Stat. 1136 (1909), 18 U.S.C. §§ 388–390; white slave traffic, 36 Stat. 825 (1910), 18 U.S.C. §§ 397–404; transportation of prize-fight films, 37 Stat. 240 (1912), 18 U.S.C. §§ 405–407; larceny of goods moving in interstate commerce, 37 Stat. 670 (1913), 18 U.S.C. § 409; violent interference with foreign commerce, 40 Stat. 221 (1917), 18 U.S.C. § 381; transportation of stolen motor vehicles, 41 Stat. 324 (1919), 18 U.S.C. § 408; transportation of kidnapped persons, 47 Stat. 326 (1932), 18 U.S.C. § 408a–408c; threatening communication in interstate commerce, 48 Stat. 781 (1934), 18 U.S.C. § 408d; transportation of stolen or feloniously taken goods, securities or money, 48 Stat. 794 (1934), 18 U.S.C. § 415; transporting strikebreakers, 49 Stat. 1899 (1936), 18 U.S.C. § 407a; destruction or dumping of farm products received in interstate commerce, 44 Stat. 1355 (1927), 7 U.S.C. § 491. Cf.

National Labor Relations Act, 49 Stat. 449 (1935), 29 U.S.C., Ch. 7, § 151,

«Findings and declaration of policy. The denial by employers of the right of employees to organize and the refusal by employers to accept the procedure of collective bargaining lead to strikes and other forms of industrial strife or unrest, which have the intent or the necessary effect of burdening or obstructing commerce. . . .»

The Anti-Racketeering Act, 48 Stat. 979, 18 U.S.C. §§ 420a-420e (1934), is designed to protect trade and commerce against interference by violence and threats. § 420a provides that

«any person who, in connection with or in relation to any act in any way or in any degree affecting trade or commerce or any article or commodity moving or about to move in trade or commerce —»

«(a) Obtains or attempts to obtain, by the use of or attempt to use or threat to use force, violence, or coercion, the payment of money or other valuable considerations . . . not including, however, the payment of wages by a bonafide employer to a bona fide employee; or»

«(b) Obtains the property of another, with his consent, induced by wrongful use of force or fear, or under color of official right; or»

«(c) Commits or threatens to commit an act of physical violence or physical injury to a person or property in furtherance of a plan or purpose to violate subsections (a) or (b); or»

«(d) Conspires or acts concertedly with any other person or persons to commit any of the foregoing acts; shall, upon conviction thereof, be guilty of a felony and shall be punished by imprisonment from one to ten years or by a fine of $10,000 or both.»

But the application of the provisions of § 420a to labor unions is restricted by § 420d, which provides:

«Jurisdiction of offenses. Any person charged with violating section 420a of this title may be prosecuted in any district in which any part of the offense has been committed by him or by his actual associates participating with him in the offense or by his fellow conspirators: Provided, That no court of the United States shall construe or apply any of the provisions of sections 420a to 420e of this title in such manner as to impair, diminish, or in any manner affect the rights of bona fide labor organizations in lawfully carrying out the legitimate objects thereof, as such rights are expressed in existing statutes of the United States.»

It is significant that Chapter 9 of the Criminal Code, dealing with «Offenses Against Foreign And Interstate Commerce» and relating specifically to acts of interstate transportation or its obstruction, makes no mention of the Sherman Act, which is made a part of the Code which deals with social, economic and commercial results of interstate activity, notwithstanding its criminal penalty.»

- ^ Footnote 15 appears here:

«The history of the Sherman Act, as contained in the legislative proceedings, is emphatic in its support for the conclusion that «business competition» was the problem considered, and that the act was designed to prevent restraints of trade which had a significant effect on such competition.

On July 10, 1888, the Senate adopted without discussion a resolution offered by Senator Sherman which directed the Committee on Finance to inquire into, and report in connection with, revenue bills

«such measures as it may deem expedient to set aside, control, restrain or prohibit all arrangements, contracts, agreements, trusts, or combinations between persons or corporations, made with a view, or which tend to prevent free and full competition . . . with such penalties and provisions . . . as will tend to preserve freedom of trade and production, the natural competition of increasing production, the lowering of prices by such competition . . .»

(19 Cong.Rec. 6041).

This resolution explicitly presented the economic theory of the proponents of such legislation. The various bills introduced between 1888 and 1890 follow the theory of this resolution. Many bills sought to make void all arrangements

«made with a view, or which tend, to prevent full and free competition in the production, manufacture, or sale of articles of domestic growth or production, . . .»

S. 3445; S. 3510; H.R. 11339; all of the 50th Cong., 1st Sess. (1888) were bills of this type. In the 51st Cong. (1889), the bills were in a similar vein. See S. 1, sec. 1 (this bill as redrafted by the Judiciary Committee ultimately became the Sherman Law); H.R. 202, sec. 3; H.R. 270; H.R. 286; H.R. 402; H.R. 509; H.R. 826; H.R. 3819. See Bills and Debates in Congress relating to Trusts (1909), Vol. 1, pp. 1025–1031.

Only one, which was never enacted, S. 1268 in the 52d Cong., 1st Sess. (1892), introduced by Senator Peffer, sought to prohibit

«every willful act . . . which shall have the effect to in any way interfere with the freedom of transit of articles in interstate commerce, . . .»

When the antitrust bill (S. 1, 51st Cong., 1st Sess.) came before Congress for debate, the debates point to a similar purpose. Senator Sherman asserted the bill prevented only «business combinations» «made with a view to prevent competition», 21 Cong.Rec. 2457, 2562; see also ibid. at 2459, 2461.

Senator Allison spoke of combinations which «control prices,» ibid., 2471; Senator Pugh of combinations «to limit production» for «the purpose of destroying competition», ibid., 2558; Senator Morgan of combinations «that affect the price of commodities,» ibid., 2609; Senator Platt, a critic of the bill, said this bill proceeds on the assumption that «competition is beneficent to the country,» ibid., 2729; Senator George denounced trusts which crush out competition, «and that is the great evil at which all this legislation ought to be directed,» ibid., 3147.

In the House, Representative Culberson, who was in charge of the bill, interpreted the bill to prohibit various arrangements which tend to drive out competition, ibid., 4089; Representative Wilson spoke in favor of the bill against combinations among

«competing producers to control the supply of their product, in order that they may dictate the terms on which they shall sell in the market, and may secure release from the stress of competition among themselves,»

ibid., 4090.

The unanimity with which foes and supporters of the bill spoke of its aims as the protection of free competition permits use of the debates in interpreting the purpose of the act. See White, C.J. in Standard Oil Co. v. United States, 221 U. S. 50 Archived 2009-05-01 at the Wayback Machine; United States v. San Francisco, ante, p. 310 U. S. 16 Archived 2009-05-25 at the Wayback Machine.

See also Report of Committee on Interstate Commerce on Control of Corporations Engaged in Interstate Commerce, S.Rept. 1326, 62d Cong., 3d Sess. (1913), pp. 2, 4; Report of Federal Trade Commission, S.Doc. 226, 70th Cong., 2d Sess. (1929), pp. 343–345.»

- ^ See 15 U.S.C. § 1.

- ^ See 15 U.S.C. § 2.

- ^ States, United (March 26, 2018). «Sherman Anti-trust Law and List of Decisions Relating Thereto». U.S. Government Printing Office – via Google Books.

- ^ «An Early Assessment of the Sherman Antitrust Act: Three Case Studies». Archived from the original on September 26, 2015. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ^ «United States v. General Electric Co., 82 F. Supp. 753 (D.N.J. 1949)». Justia Law. April 4, 1949. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- ^ E.g., Richter Concrete Corp. v. Hilltop Basic Resources, Inc., 547 F. Supp. 893, 917 (S.D. Ohio 1981), aff’d, 691 F.2d 818 (6th Cir. 1982); Consolidated Farmers Mut. Ins. Co. v. Anchor Sav. Association, 480 F. Supp. 640, 648 (D. Kan. 1979); Mardirosian v. American Inst. of Architects, 474 F. Supp. 628, 636 (D.D.C. 1979).

- ^ United States v. Grinnell Corp., 384 U.S. 563, 570–71 (1966); see also Weiss v. York Hosp., 745 F.2d 786, 825 (3d Cir. 1984).

- ^ The truth is that our categories of analysis of anticompetitive effect are less fixed than terms like ‘per se,’ ‘quick look,’ and ‘rule of reason’ tend to make them appear. We have recognized, for example, that ‘there is often no bright line separating per se from rule of reason analysis,’ since ‘considerable inquiry into market conditions’ may be required before the application of any so-called ‘per se’ condemnation is justified. Cal. Dental Association v. FTC at 779 (quoting NCAA, 468 U.S. at 104 n.26). «‘Whether the ultimate finding is the product of a presumption or actual market analysis, the essential inquiry remains the same whether or not the challenged restraint enhances competition.'» 526 U.S. at 779–80 (quoting NCAA, 468 U.S. at 104).

- ^ Continental T.V., Inc. v. GTE Sylvania Inc., 433 U.S. 36, 58 (1977) (quoting Northern Pac. Ry. v. United States, 356 U.S. 1, 5 (1958)).

- ^ Broadcast Music, Inc. v. CBS, 441 U.S. 1, 19–20 (1979).

- ^ Jefferson Parish Hosp. Dist. No. 2 v. Hyde, 466 U.S. 2 (1984); Gough v. Rossmoor Corp., 585 F.2d 381, 386–89 (9th Cir. 1978), cert. denied, 440 U.S. 936 (1979); see White Motor v. United States, 372 U.S. 253, 259–60 (1963) (a per se rule forecloses analysis of the purpose or market effect of a restraint); Northern Pac. Ry., 356 U.S. at 5 (same).

- ^ United States v. Trenton Potteries Co., 273 U.S. 392, 397–98 (1927).

- ^ Continental T.V., 433 U.S. at 50 n. 16 (limiting United States v. Topco Assocs., 405 U.S. 596, 608 (1972) by making vertical market division rule-of-reason analysis).

- ^ FTC v. Superior Court Trial Lawyers Ass’n, 493 U.S. 411 for collusive effects and NW Wholesale Stationers, Inc. v. Pacific Stationery & Printing Co., 472 U.S. 284 (1985) for exclusionary effects.

- ^ Continental T.V., 433 U.S. at 49. The inquiry focuses on the restraint’s effect on competition. National Soc’y of Professional Eng’rs v. United States, 435 U.S. 679, 691 (1978).

- ^ National Soc’y of Professional Eng’rs, 435 U.S. at 692.

- ^ See Continental T.V., 433 U.S. at 45 (citing United States v. Arnold, Schwinn & Co., 388 U.S. 365, 382 (1967)), and geographic market, see United States v. Columbia Steel Co., 334 U.S. 495, 519 (1948).

- ^ Continental T.V., 433 U.S. at 49; see Standard Oil Co. v. United States, 221 U.S. 1, 58 (1911) (Congress only intended to prohibit agreements that were «unreasonably restrictive of competitive (conditions»).

- ^ Cal. Dental Ass’n, 526 U.S. at 770.

- ^ a b Clark, O. L. (January 1948). «Application of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act to Unions since the Apex Case». SMU Law Review. 1 (1): 94–103.

- ^ See Loewe v. Lawlor, 208 U.S. 274 (1908).

- ^ See Exxon Corp. v. Governor of MD., 437 U.S. 117, 130–34 (1978) (state law with anticompetitive effect upheld to avoid destroying the ability of the states to regulate economic activity); Conant, supra note 1, at 264., Werden & Balmer, supra note 1, at 59. See generally 1 P. Areeda & D. Turner, Antitrust Law P208 (1978) (discussing the interaction of state and federal antitrust laws); id. P210 (discussing areas where federal law expressly defers to state law).

- ^ Rice, 458 U.S. at 661. If a statute does not require a per se violation, then it cannot be preempted on its face. Id.

- ^ See [Rice, 458 U.S. at 661.]

- ^ National Soc’y of Professional Eng’rs v. United States, 435 U.S. 679, 687–90 (1978); Continental T.V., Inc. v. GTE Sylvania Inc., 433 U.S. 36, 49 (1977)

- ^ See Battipaglia v. New York State Liquor Auth., 745 F.2d 166, 175 (2d Cir. 1984) (while declining to decide whether a statute required an antitrust violation in a facial attack, the court left open the possibility of preemption based on the statute’s operation), cert. denied, 105 S. Ct. 1393 (1985); Lanierland Distribs. v. Strickland, 544 F. Supp. 747, 751 (N.D. Ga. 1982) (plaintiff failed to show anticompetitive effects sufficient to violate the rule of reason); Wine & Spirits Specialty, Inc. v. Daniel, 666 S.W.2d 416, 419 (Mo.) (en banc) (declining to decide whether the rule of reason might invalidate a law on the record before them), Appeal dismissed, 105 S. Ct. 56 (1984); United States Brewers Ass’n v. Director of N.M. Dept’ of Alcoholic Beverage Control, 100 N.M. 216, , 668 P.2d 1093, 1099 (1983) (rejecting a facial attack on a statute but reserving a decision on whether the actual application of the statute might violate the antitrust laws), appeal dismissed, 104 S. Ct. 1581 (1984). But see infra note 149 for a discussion on the possibility of a much more limited rule of reason preemption analysis.

- ^ See Rice, 458 U.S. at 662–63 n.9 («because of our resolution of the pre-emption issue, it is not necessary for us to consider whether the statute may be saved from invalidation under the [state action] doctrine»); Capitol Tel. Co. v New York Tel. Co., 750 F.2d 1154, 1157, 1165 (2d Cir. 1984) (holding that the state action doctrine protected the conduct of a private party after assuming that it violated the federal antitrust laws), cert. denied, 105 S. Ct. 2325 (1985); Allied Artists Picture Corp. v. Rhodes, 679 F.2d 656, 662 (6th Cir. 1982) (even if conduct violated Sherman Act, the statute is saved by the state action doctrine); Miller v. Hedlund, 579 F. Supp. 116, 124 (D. Or. 1984) (statute violating Section 1 saved by state action); Flav-O-Rich, Inc. v. North Carolina Milk Comm’n, 593 F. Supp. 13, 17–18 (E.D.N.C. 1983) (though conduct violates Section 1, state action saves statute).

- ^ Rice v. Norman Williams Co., 458 U.S. 654, 659 (1982).

- ^ Id. at 668 (Stevens, J., concurring in the judgment).

- ^ See Grendel’s Den, Inc. v. Goodwin, 662 F.2d 88, 100 n.15 (1st Cir.) (power to control others not sufficient for facial preemption where party had no institutional reason to make anticompetitive decisions especially likely), aff’d on other grounds, 662 F.2d 102 (1st Cir. 1981) (en banc), aff’d sub nom. Larkin v. Grendel’s Den, Inc., 459 U.S. 116 (1982); Flav-O-Rich, Inc. v. North Carolina Milk Comm’n, 593 F. Supp. 13, 15 (E.D.N.C. 1983) (in an oligopolistic market, price posting would result in an antitrust violation).

- ^ But cf. Allied Artists Pictures Corp. v. Rhodes, 496 F. Supp. 408, 449 (S.D. Ohio 1980) (indicating that a statute neither requiring nor permitting an anticompetitive collaboration gives the private party enough freedom of choice to preclude preemption), aff’d in part and remanded in part, 679 F.2d 656 (6th Cir. 1982)

- ^ Rice, 458 U.S. at 659.

- ^ Id. (citing New Motor Vehicle Bd. v. Orrin W. Fox Co., 439 U.S. 96, 110–11 (1978); Exxon Corp. v. Governor of MD., 437 U.S. 117, 129–34 (1978); Joseph E. Seagram & Sons v. Hostetter, 384 U.S. 35, 45–46 (1966)).

- ^ New Motor Vehicle Bd. v. Orrin W. Fox Co., 439 U.S. 96, 110–11 (1978) (quoting Exxon Corp. v. Governor of MD., 437 U.S. 117, 133 (1978)).

- ^ Rice v. Norman Williams Co., 458 U.S. 654, 662 (1982).

- ^ H.R.Rep. No. 1707, 51st Cong., 1st Sess., p. 1.

- ^ 21 Cong.Rec. 4089.

- ^ 21 Cong.Rec. 3148

- ^ 21 Cong.Rec. 3152.

- ^ «Antitrust, by Alan Greenspan». Archived from the original on February 17, 2022. Retrieved April 7, 2022.

- ^ Criticisms such as this one, attributed to Greenspan, are not directed at the Sherman act in particular, but rather at the underlying policy of all antitrust law, which includes several pieces of legislation other than just the Sherman Act, e.g. the Clayton Antitrust Act.

- ^ Check Your Premises, The Objectivist Newsletter, January 1962, vol. 1, no. 1, p. 1

- ^ Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal, Ch. 3, New American Library, Signet, 1967

- ^ Congressional Record, 51st Congress, 1st session, House, June 20, 1890, p. 4100.

- ^ «Mr. Sherman’s Hopes and Fears» (PDF). The New York Times. October 1, 1890. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 24, 2019. Retrieved April 21, 2008.

- ^ DiLorenzo, Thomas, Cato Handbook for Congress, Antitrust.

- ^ a b Richard Posner, Economic Analysis of Law, p. 295 et seq. (explaining the optimal antitrust regime from an economic point of view)

- ^ Douglas, William O., An Almanac of Liberty, Doubleday & Company, 1954, p. 189

- ^ Newman, Patrick (January 12, 2018). «Revenge: John Sherman, Russell Alger and the origins of the Sherman Act». Public Choice. 174 (3–4): 257–275. doi:10.1007/s11127-017-0497-x. ISSN 0048-5829. S2CID 158141317.

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Sherman Act as amended (PDF/details) in the GPO Statute Compilations collection

- Official websites

- U.S. Department of Justice: Antitrust Division

- U.S. Department of Justice: Antitrust Division – text of SHERMAN ANTITRUST ACT, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1–7

- Additional information

- Antitrust Division’s «Corporate Leniency Policy»

- Antitrust by Alan Greenspan

- «Labor and the Sherman Act» (1940). Yale Law Journal 49(3) p. 518. JSTOR 792668.

- Dr. Edward W. Younkins (February 19, 2000). «Antitrust Laws Should Be Abolished».

В конце 19 века монополизм в США достиг своего апогея.

В конце 19 века монополизм в США достиг своего апогея. Особенно выделялась компания Джона Рокфеллера Standard Oil, захватившая 95% рынка нефтепродуктов США.

Сенатор-республиканец Джон Шерман инициировал законопроект, согласно которому запрещалось мешать свободе торговле путем создания трестов и сговоров о контроле рынка. Формально закон начал действовать с 2 июля 1890 года, но особенно активно стал использоваться с приходом к власти Теодора Рузвельта (президент США с 1901 по 1909 гг.). Акт Шермана, в измененном виде, имеет силу и сейчас и входит в федеральный Кодекс США.

Акт Шермана можно было использовать как против предприятий, так и против профсоюзов (в 1914 был принят Акт Клейтона и профсоюзы перестали попадать под действие закона), которые, по сути, представляли собой монополии на рынке труда.

Первое дело, связанное с Актом Шермана, было проиграно правительством. Верховный Суд США снял обвинения против сахарного монополиста в American Sugar Refining Company в 1893 г.

В 1904 году было выигран первый громкий процесс: в соответствие с законом Шермана, компания Northern Securities была признана виновной в объединении железных дорог.

В 1904 году был подан ряд антимонопольных исков против Standard Oil. В 1911 году Верховный Суд США утвердил решение о разделении компании (надо отметить, что Рокфеллер, раздробив Standard Oil на 34 фирмы, сохранил контроль над ними).

Интересно, что есть исследования, говорящие о том, что после принятия Акта Шермана снижение цен и рост выпуска продукции во многих отраслях замедлились (De Lorme C.D., Frame W.S. and Kamerschen D.R. Spezial-Interest-group Perspective Bevore and After the Clayton And Federal Trade Commision Acts // Applied Ecjnjmics. — 1996. — V. 28. — № 7.)

What Is the Sherman Antitrust Act?

The Sherman Antitrust Act refers to a landmark U.S. law that banned businesses from colluding or merging to form a monopoly. Passed in 1890, the law prevented these groups from dictating, controlling, and manipulating prices in a particular market.

The act aimed to promote economic fairness and competitiveness while regulating interstate commerce. The Sherman Antitrust Act was the U.S. Congress’ first attempt to address the use of trusts as a tool that enables a limited number of individuals to control certain key industries.

Key Takeaways

- The Sherman Antitrust Act is a law the U.S. Congress passed to prohibit trusts, monopolies, and cartels.

- Its purpose was to promote economic fairness and competitiveness and to regulate interstate commerce.

- Ohio Sen. John Sherman proposed and passed it in 1890.

- The act signaled an important shift in American regulatory strategy toward business and markets.

- The Sherman Act was amended by the Clayton Antitrust Act in 1914, which addressed specific practices that the Sherman Act did not ban.

Understanding the Sherman Antitrust Act

Sen. John Sherman from Ohio proposed the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890. It was the first measure the U.S. Congress passed to prohibit trusts, monopolies, and cartels from taking over the general market. It also outlawed contracts, conspiracies, and other business practices that restrained trade and created monopolies within industries.

At the time, public hostility was growing toward large corporations like Standard Oil and the American Railway Union, which were seen as unfairly monopolizing certain industries. Consumers felt they were hit with exorbitantly high prices on essential goods, while competitors found themselves shut out because of deliberate attempts by large corporations to keep other enterprises out of the market.

This signaled an important shift in the American regulatory strategy toward business and markets. After the 19th-century rise of big business, American lawmakers reacted with a drive to regulate business practices more strictly. The Sherman Antitrust Act paved the way for more specific laws like the Clayton Act. Measures like these had widespread popular support, but lawmakers genuinely wanted to keep the American market economy broadly competitive in the face of changing business practices.

Competing individuals or businesses are not permitted to fix prices, divide markets, or attempt to rig bids. It also lays out specific penalties and fines intended for businesses that violate these rules. The act can impose both civil and criminal penalties on companies that don’t comply.

The Sherman Antitrust Act was not designed to prevent healthy monopolistic competition but to target monopolies that resulted from a deliberate attempt to dominate the marketplace.

Special Considerations

Antitrust laws refer broadly to the group of state and federal laws designed to ensure that businesses are competing fairly. These laws exist to promote competition among sellers, limit monopolies, and give consumers options.

Supporters say these laws are necessary for an open marketplace to exist and thrive. Competition is considered healthy for the economy, giving consumers lower prices, higher-quality products and services, more choice, and greater innovation.

However, opponents argue that allowing businesses to compete as they see fit—instead of regulating competition—would ultimately give consumers the best prices.

Sections of the Sherman Antitrust Act

The Sherman Antitrust Act is divided into three key sections:

- Section 1: This section defines and bans specific means of anti-competitive conduct.

- Section 2: This section addresses end results that are by their nature anti-competitive.

- Section 3: This section extends these guidelines and provisions to the District of Columbia and U.S. territories.

Early issues and amendments

The act received immediate public approval. But because the legislation’s definition of concepts such as trusts, monopolies, and collusion was not clearly defined, few business entities were actually prosecuted under its measures.

The Sherman Antitrust Act was amended by the Clayton Antitrust Act in 1914, which addressed specific practices that the Sherman Act did not ban. It also closed loopholes that the Sherman Act established, including those that dealt specifically with anti-competitive mergers, monopolies, and price discrimination.

For example, the Clayton Act prohibits appointing the same person to make business decisions for competing companies.

Historical Context of the Sherman Antitrust Act

The Sherman Antitrust Act was born against a backdrop of increasing monopolies and abuses of power by large corporations and railroad conglomerates.

The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC)

Congress passed the Interstate Commerce Act in 1887 in response to increasing public indignation about abuses of power and malpractices by railroad companies. This spawned the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC). Its purpose was to regulate interstate transportation entities. The ICC had jurisdiction over U.S. railroads and all common carriers, requiring them to submit annual reports and prohibiting unfair practices such as discriminatory rates.

During the first half of the 20th century, Congress consistently expanded the ICC’s power so much that, despite its intended purpose, some believed that the ICC was often guilty of assisting the very companies it was tasked to regulate by favoring mergers that created unfair monopolies.

The Gilded Age

Congress passed the Sherman Antitrust Act at the height of what Mark Twain called the Gilded Age of American history. The Gilded Age, which spanned from the 1870s to about 1900, was dominated by political scandal and robber barons, the growth of railroads, the expansion of oil and electricity, and the development of America’s first giant (national and international) corporations.

The Gilded Age was an era of rapid economic growth. Corporations took off during this time, in part because they were easy to register and, unlike today, did not have to pay any incorporation fees.

Trusts in the 19th Century

Late-19th-century legislators’ understanding of trusts is different from our current concept of the term. During that time, trusts became an umbrella term for any sort of collusive or conspiratorial behavior that was seen to render competition unfair. The term trust has evolved over the years, though. Today, it refers to a financial relationship in which one party gives another the right to hold property or assets for a third party.

Example of the Sherman Antitrust Act

On Oct. 20, 2020, the U.S. Department of Justice filed an antitrust lawsuit against Google, alleging that the online giant engaged in anti-competitive conduct to preserve monopolies in search and search advertising. Deputy Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen compared the complaint to past uses of the Sherman Act to stop monopolistic practices by corporations.

“As with its historic antitrust actions against AT&T in 1974 and Microsoft in 1998, the Department is again enforcing the Sherman Act to restore the role of competition and open the door to the next wave of innovation—this time in vital digital markets,” Rosen said in a press release.

What Is the Sherman Antitrust Act in Simple Terms?

The Sherman Antitrust Act is a law passed by Congress to promote competition within the economy by prohibiting companies from colluding or merging to form a monopoly.

Why Was the Sherman Antitrust Act Passed?

The Sherman Antitrust Act was passed to address concerns by consumers who felt they were paying high prices on essential goods and by competing companies who believed they were being shut out of their industries by larger corporations.

What Are the Penalties for Violating the Sherman Act?

Those found guilty of violating the Sherman Act can face a hefty punishment. It is also a criminal law, and offenders may serve prison sentences of up to 10 years. Beyond that, there are also fines, which can be up to $1 million for an individual and up to $100 million for a corporation. In some cases, heftier fines could also be issued, worth twice the amount the conspirators gained from the illegal acts or twice the money lost by the victims.

Have Any of Today’s Big-Name Companies Been Accused of Violating the Sherman Act?

Many household names have been hit with antitrust suits based in part on the Sherman Act. Other than Google, in recent years Microsoft and Apple have both faced complaints, with the former accused of seeking to create a monopoly in Internet browser software and the latter of unethically raising the price of its e-books and, in later years, exploiting the market power of its app store.

What Is the Difference Between the Sherman Act and the Clayton Act?

The Clayton Act was introduced later, in 1914, to address some of the specific practices that the Sherman Act did not clearly prohibit or failed to properly clarify. The Sherman Act, the first of its kind, was deemed too vague, allowing some companies to find ways to maneuver around it.

Essentially, the Clayton Act deals with similar topics, such as anti-competitive mergers, monopolies, and price discrimination but adds more detail and scope to eliminate some of the previous loopholes. Over the years, antitrust laws continue to be amended to reflect the current business environment and fresh observations.

Что такое Антимонопольный закон Шермана?

Антимонопольный закон Шермана (Закон) – это знаковый закон США, принятый в 1890 году, который объявил трасты вне закона – группы предприятий, которые вступают в сговор или объединяются в монополию , чтобы диктовать цены на определенном рынке. Цель закона заключалась в содействии экономической справедливости и конкурентоспособности, а также в регулировании межгосударственной торговли. Антимонопольный закон Шермана стал первой попыткой Конгресса США решить проблему использования трастов в качестве инструмента, позволяющего ограниченному кругу лиц контролировать определенные ключевые отрасли.

Значение антимонопольного законодательства

Антимонопольное законодательство в целом относится к группе законов штата и федеральных законов, призванных обеспечить справедливую конкуренцию между предприятиями. Антимонопольные законы существуют для поощрения конкуренции между продавцами, ограничения монополий и предоставления потребителям выбора.

Сторонники говорят, что антимонопольное законодательство необходимо для существования и процветания открытого рынка. Конкуренция между продавцами дает потребителям более низкие цены, более качественные продукты и услуги, больший выбор и больше инноваций. Противники утверждают, что разрешение предприятиям конкурировать так, как они считают нужным, в конечном итоге даст потребителям лучшие цены.

Знаковый закон

Антимонопольный закон Шермана, предложенный в 1890 году сенатором от штата Огайо Джоном Шерманом, был первой мерой, принятой Конгрессом США для запрещения трестов, монополий и картелей . Закон Шермана также объявил вне закона контракты, заговоры и другие виды деловой практики, которые ограничивали торговлю и создавали монополии внутри отраслей. Например, в Законе Шермана говорится, что конкурирующие физические и юридические лица не могут устанавливать цены, делить рынки или пытаться подтасовывать ставки. В законе также предусмотрены конкретные меры наказания и штрафы за нарушение его правил.

Краткая справка

Закон был разработан не для предотвращения здоровой конкуренции или монополий, которые были достигнуты честными или органическими средствами, а для борьбы с теми монополиями, которые возникли в результате преднамеренной попытки доминировать на рынке.

Антимонопольный закон Шермана был изменен Антимонопольным законом Клейтона в 1914 году, который касался конкретных практик, которые Закон Шермана не запрещал. Например, Закон Клейтона запрещает назначать одно и то же лицо для принятия деловых решений для конкурирующих компаний.

Ключевые моменты

- Антимонопольный закон Шермана – первая мера, принятая Конгрессом США, запрещающая трасты, монополии и картели.

- Цель закона заключалась в содействии экономической справедливости и конкурентоспособности, а также в регулировании межгосударственной торговли.

- Он был предложен и принят в 1890 году сенатором от Огайо Джоном Шерманом.

- Антимонопольное законодательство Шермана было довольно популярным и сигнализировало о важном сдвиге в американской стратегии регулирования в отношении бизнеса и рынков.

Историческая справка

Межгосударственная торговая комиссия (ICC)

Антимонопольный закон Шермана родился на фоне роста монополий и злоупотреблений властью со стороны крупных корпораций и железнодорожных конгломератов . В 1887 году в ответ на растущее возмущение общественности по поводу злоупотреблений властью и недобросовестных действий со стороны железнодорожных компаний Конгресс принял Закон о торговле между штатами, который породил Комиссию по межгосударственной торговле (ICC), цель которой заключалась в регулировании транспортных предприятий между штатами . В частности, ICC имела юрисдикцию над железными дорогами США и всеми распространенными перевозчиками, требуя от них представления годовых отчетов и запрещая недобросовестные действия, такие как дискриминационные ставки.

Однако в течение первой половины 20-го века Конгресс последовательно расширял власть ICC, так что, несмотря на ее предполагаемую цель, некоторые считали, что ICC часто виновата в оказании помощи тем самым компаниям, которые ей было поручено регулировать, – поддерживая слияния, которые создавали несправедливые монополии, например.

Позолоченный век

Конгресс принял Антимонопольный акт Шермана в разгар того, что Марк Твен назвал «позолоченным веком» в американской истории. Позолоченный век, который наступил с 1870-х до примерно 1900 года, был периодом, когда доминировали политические скандалы и бароны-разбойники , рост железных дорог, экономия нефти и электроэнергии и развитие первых в Америке гигантских национальных и международных корпораций .

«Золотой век» был эпохой быстрого экономического роста. Корпорации взлетели в это время, отчасти потому, что их было легко зарегистрировать и, в отличие от сегодняшнего дня, не было регистрационных сборов.

Понятие «трасты» в XIX веке

Понимание «трастов» законодателями конца 19 века отличается от нашего понимания этого термина. Сегодня доверие относится к финансовым отношениям, в которых одна сторона дает другой право владеть имуществом или активами для третьей стороны. Однако в XIX веке траст стал общим термином для обозначения любого вида сговора или конспиративного поведения, которое, как считалось, делало конкуренцию несправедливой. Антимонопольный закон Шермана был разработан не для предотвращения здоровой монополистической конкуренции , а для борьбы с теми монополиями, которые возникли в результате преднамеренной попытки доминировать на рынке.

Влияние антимонопольного закона Шермана

Закон был принят во время крайней враждебности общества по отношению к крупным корпорациям, таким как Standard Oil и Американский железнодорожный союз, которые, как считалось, несправедливо монополизировали определенные отрасли. Этот протест исходил как от потребителей, которым наносили ущерб непомерно высокие цены на товары первой необходимости, так и от конкурентов в производстве, которые оказались вне отрасли из-за преднамеренных попыток некоторых компаний удержать другие предприятия от выхода на рынок.

США против Google

20 октября 2020 года Министерство юстиции США подало антимонопольный иск против Google, утверждая, что онлайн-гигант ведет антиконкурентную политику, чтобы сохранить монополии в поиске и поисковой рекламе.Заместитель генерального прокурора Джеффри Розен сравнил жалобу с прошлым применением Закона Шермана для прекращения монополистической практики корпораций.«Как и в случае с его историческими антимонопольными действиями против AT&T в 1974 году и Microsoft в 1998 году, Департамент снова применяет Закон Шермана, чтобы восстановить роль конкуренции и открыть дверь для следующей волны инноваций – на этот раз на жизненно важных цифровых рынках», – сказал Розен. говорится в пресс-релизе1 .

Краткая справка

Закон получил немедленное общественное одобрение, но поскольку определение в законодательстве таких понятий, как трасты, монополии и сговор, не было четко определено, лишь немногие субъекты хозяйствования фактически подверглись судебному преследованию в соответствии с его мерами.